The Perils of Hero Worship

Given that Nadine Dorries seems to do little else at the moment but slaver on aimlessly about Dr Sunny Anand – Dorries was, at one time, a nurse, and you know how these nurse-doctor things are, especially when it provokes remarks like this:

You just knew you were in the presence of a very learned, great and humble man – the atmosphere in the Grand Committee Room when he spoke to a rapt audience endorsed this.

(Any more of this nauseating gushing and I may have to ask whether she also took the time to conduct her own inquiry into whether Anand has been circumcised or not – on current evidence, let’s hope they don’t do strip searches at Little Rock’s nearest airport, he might have a problem or two explaining the lipstick ring)

I think its worth posting a follow-up from my comments on the meeting organised Nadine Dorries in regards to the ‘important evidence’ that was (in Dorries’ view) ‘excluded’ from the Science and Technology Committee’s report on ‘Scientific Developments relating to the Abortion Act 1967‘, picking up on Dorries’ comments about the meeting on her own website.

First things first, let’s get an accurate definition of ‘excluded’ in place in regards to her claim that Anand’s work was ‘excluded’ from the committee report.

You may well think, not unreasonably, that ‘excluded’ means that the evidence to which Dorries refers was given no consideration whatsoever – that is undoubtedly what she would like people to think. But, in reality, the Committee’s deliberations on this evidence take up around 3-4 pages of the report and what ‘excluded’ actually means here is that the Committee declined to accept Dorries’ preferred (and entirely unqualified) interpretation of this evidence in favour of an interpretation which placed the evidence in its correct scientific context.

Another word that we need to carefully define in this debate is ‘bias’.

Dorries has claimed, repeatedly, that the Committee was biased in its deliberations because it failed to give equal prominence to her preferred arguments and failed to call roughly the same number of witnesses who expressed opposition to legal abortion or called for a reduction in the upper limit for abortions as it did those who are, broadly, supportive of the right to legal abortions and of retaining the current limits. In short, Dorries thinks that something is biased if it fails to give the same prominence to bad arguments as it does to good ones, and having read the various written submissions to the committee can I say that boy there were some very poor arguments put forward indeed, the most spectacularly offensive being that advanced by the Guild of Catholic Doctors who (and I’m not kidding here) opined that:

We in the Guild of Catholic Doctors believe that, apart from an ethical argument, which is proscribed by your committee on this occasion, the 40 years of abortion, largely “on demand”, have had a number of serious ill-effects on our Society:-

1. The effect of the loss of 6 million, largely healthy, young citizens from our society as a result of abortion is impossible to calculate, but it has seriously diminished our capability of looking after ourselves, without outside help, and has led, to some extent, to the large requirement for immigration which our economy now has.

So that’s where politicians have been going wrong on immigration. It’s not border controls we need but unfettered breeding.

(Why, I wonder, does the Catholic mindset so often seem to think that the answer to just everything involves everyone breeding like rabbits?)

It turns out, just to clear up one loose end from yesterday, that the third expert that Dorries invited to her little soiree was Dr Stuart Derbyshire, who declined the invitation to formally address the meeting – her brief account of his decision makes for interesting reading.

Professor Anand is neither pro or anti abortion, but a scientist who simply deals with the facts.

The facts unfortunately didn’t fit with the majority pro-abortion view on the Select Committee.

Professor Anand was, however, attacked by Dr Derbyshire in a letter subsequently published in The Times.

So I thought, OK then, face to face is far more preferable than letters in a newspaper – if Dr Derbyshire feels so strongly, let’s put him up against Professor Anand on the panel, two competing views.

Dr Derbyshire declined the invitation, claiming the panel would be biased; excuse me? I asked two foetal pain experts, Anand and himself – i.e. two competing views – how is that biased?

I’ll come to Dr Anand’s personal views on abortion, such as they are, in due course but, for the moment let’s concentrate on how Dorries tries to ’sell’ his work and Dr Derbyshire’s decision not to formally participate in the debate.

Dr Anand, according to Dorries, is just a ’scientist who simply deals with the facts’ and not only that but one who deals with ‘facts’ that ‘didn’t fit with the majority pro-abortion view on the Select Committee’ – all of which is tendentious nonsense.

What Dr Anand actually deals with, as a scientist, is a theory (his own) about whether foetuses ‘experience’ pain and, if so, from what point in their development, together with evidence obtained from experimentation and observational studies and interpretations of that evidence in light of the extent to which it supports or rebuts elements of his theory. In science, the combination of theory plus supporting evidence plus interpretation may well lead us to identify certain facts, or it may lead only so far as identifying further questions which require further investigation, which in terms of foetal pain is a fair assessment of the stage that Dr Anand’s work has reached.

What his work has demonstrated is that, from around 20 weeks gestation, the foetus develops a number of elements of the biological capacity to ‘feel’ pain – at that stage of development, a foetus can and does respond to pain stimuli transmitted by the nerves to the brain’s subcortex in certain, limited, ways that are analogous to the biological processes that occur following birth. Without getting into the full biochemistry the basic equation is that pain causes stress which results in the body releasing ’stress hormones’ which, in turn, trigger certain physiological responses.

This is actually very important work… in the right context, which is that in which invasive medical procedures are carried out on foetuses, in the womb, in order to correct developmental defects that might otherwise prove limiting once the foetus is born or increase the risk of stillbirth/early death, because what his work has shown is that the release of stress hormones in response to pain stimuli at this point in gestation, and beyond, can have an adverse effect on later development.

In short, what Dr Anand has is an argument for the use of foetal anaesthesia in carrying out such procedures where, in the past, it was thought that physiological components of the pain response did not develop until a later stage in gestation, making the use of anaesthesia ‘unnecessary’ – or to be more precise an unnecessary risk given that there are always risks involved in the use of anaesthesia, even in adults.

This is clearly relevant to situations where the intention is that the foetus should continue to full-term but, quite obviously, the limited relevance in relation to abortion where the development of the foetus is to be terminated – at most Dr Anand’s work provides an argument for the use of anaesthesia in late-term abortions in the interests of such procedures being conducted in as humane a manner as possible, and even there the argument is a much predicated on concern for the psychological well-being of the woman undergoing the procedure than on any necessity for concern in relation to the foetus, the termination of which renders the whole question of pain ultimately moot.

What Dr Anand’s work does not demonstrate, in any material sense, is that a foetus at this stage of development, has any conscious experience of pain, even in the most rudimentary sense of the term, for the simple reason that the biological ‘machinery’ of consciousness has not, at this point, developed sufficiently to enable the foetus to undergo any such experience – in fact, at 20 weeks gestation, what there is of the structure that will eventually become the cerebral cortex (the ’seat’ of consciousness, if you like) is not even connected to the rest of the foetus’ developing nervous system – the main sequence of physiological development for conscious thought doesn’t begin to kick in until 26-28 weeks gestation and does not hit full steam until birth and, in fact, beyond for around 18 months to two years following birth. Post-birth development is of critical importance because the infant brain requires the massive increase in neural stimulation which comes with leaving the safety of the womb in order for the brain to ‘mature’ and within this maturation process there are regions of the brain (the somatosensory cortex, prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex) that have shown to be consistently associated with the capacity to experience pain, which increase in size by a third in the period from birth to 18 months.

Dr Derbyshire’s view on foetal pain, a view widely held in the scientific community, is that foetuses do not ‘feel’ pain at any point prior to birth on the grounds that the evidence indicates that its only from birth onwards that the conscious capacity to ‘feel’ and ‘experience’ pain, emotions and everything else that comes with the development of an infant into a conscious, thinking, entity and the scientific evidence for this is no less detailed or compelling than that advanced by Dr Anand in support of his theory nor, indeed, are the two positions either contradictory or in opposition to each other – both interpretations of the evidence may well be correct because where the two doctors differ is in their definition of what it means to ‘feel’ pain.

I’ve laboured the point here for two reasons.

First to expose the fallacy of Dorries’ claim to be attempting to arrange a debate between two ‘competing’ scientific views – there is no contention between the two in terms of the science that underpins their positions only a difference in interpretation of what it means to feel pain, a question for which science has yet to provide any definitive answer and which may even prove as intractable as the mind-body problem. At the very least, this is not a matter on which a lay audience is likely to reach a definitive (or even well-informed) view on the strength of an adversarial debate, not least because will find it a struggle to evaluate the science, let alone the metaphysical questions that stem from it, without engaging in a detailed studies of neurobiology, psychology and philosophy. Whatever else such rhetorical contests might be, the one thing they aren’t is science.

The second reason, as may already be apparent, is to highlight the limitations of relying on scientific evidence in this debate, one in which there is much that science cannot do – it cannot provide a definitive answer to the question of when human life (as opposed to the mere biological life process that begins with the first division of the first cell) or precisely when a foetus/infant attains consciousness and begins to think, because these are not processes that function like an on-off switch. There is no single point where one can say, definitively, that a foetus/infant has crossed the Rubicon into consciousness.

That’s not to say that the scientific debate has no value, it does but not because it provides any definitive answers.

Unless one adopts an absolutist position one way or another – i.e. one opposes abortion at any point in pregnancy or one takes the rights of the woman to be paramount right up to the point of birth – then the most one can do is arrive at a position based on a value judgement, a weighing and balancing of contending moral, ethical and practical factors (such as the rights of women against the foetus, if you ascribe rights to the latter, the social costs of abortion against the costs of ‘unwanted’ children, etc.) and in reaching such a judgement one of the major ethical (and psychological) conditions that most will seek to satisfy is that of seeking to minimise the harm caused by abortion in a scenario in which some degree of harm is inevitable.

This question is one in which science has some measure of value in helping to inform the debate. Questions such as that of when a foetus may begin to ‘feel pain and when it may attain a capacity for conscious thought are ones that will weigh heavily in our calculations when seeking to estimate a point at (or up to) which one considers that an abortion will give rise to minimum acceptable degree of harm, this being the fundamental basis of the strategy that Dorries (and those like her) have adopted in seeking to engineer public and parliamentary support for a reduction in the upper time limit for legal abortions – a strategy that, like so many others coming from the ‘Christian’ right, originated in the US.

What Dorries is relying on here to push her agenda is a carefully calculated and contrived ‘wedge’ strategy, which is based on a not unreasonable assumption that many people, especially those with a limited understanding of (and interest in) the complexities of the scientific and non-scientific questions we’re dealing with in this debate, will respond emotionally, and viscerally, to the idea that a foetus may experience pain from a particular point its development and, as importantly, will do so far more than they will to the somewhat more abstract questions of consciousness and that this will, in turn, cause many people to re-evaluate their position on what they see as (morally/ethically) correct upper legal limit on abortion.

In short, the strategy aims to exploit a belief that even if the broader moral/ethical arguments have been all but lost – public support for legal abortions is no less solid, in general terms, than it ever has been over the last forty years for all the efforts of the anti-abortion lobby to shift public opinion – they may still be able to swing the public around to arguments for tightening restrictions on abortion by engaging (and deliberately manipulating) people’s basic desire to be ‘humane’ and minimise harm.

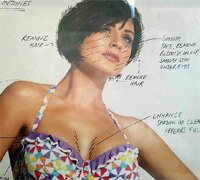

Foetal pain (as with Campbell’s ‘4D’ images, which possess little or no scientific value but which can engender a tremendous emotional ‘pull’) is a key issue for Dorries and those of her ilk, in this debate, not because it provides a scientific argument for reducing the upper limit on abortions (such an argument being, of course, easily countered by the simple expedient of using anaesthesia) but because it provides her with an emotional argument dressed up in the clothing of science, which is an altogether different thing.

(Whether Dorries is bright enough to understand the strategy she’s following or merely imitating that which has been used in the US without really understanding how and why it functions is another question entirely – although, personally, I’m more inclined to go with the dumb imitation hypothesis)

Coming full circle, this is where the assertion that Dr Anand is merely a scientist with no particular views on abortion (one way or another) starts to look shaky because the strategy that Dorries has adopted is one that:

A. Anti-abortion groups have sought to use in the US in recent years in an effort to overturn, or at least bypass, Roe vs Wade in regards to late-term abortions

B. Relies extensively, if not almost exclusively, on the use of foetal pain (and Dr Anand’s work) as the justification for imposing legal restriction on access to abortion, and, most crucially of all,

C. is one in which Dr Anand has played a direct role, as this article (by Dr Stuart Derbyshire) from Spiked notes:

While Anand has done much to advance the clinical treatment of neonates and to preserve early life, he has also done much to confuse the understanding of pain and has now damaged the credibility of medicine. His testimony in California, Nebraska and New York, for which he was paid $450 an hour, plus expenses, by the current US government, was based on an evidently dubious and shaky claim of ‘medical certainty’.

It is understandable and proper for physicians and medical experts to wield their expertise in defence of practices that they believe to enhance clinical care, but it is quite another to wield expertise against clinical care and in defence of hypothetical and unproven experiences. Unfortunately Anand has long interchanged what he believes with what he can prove and now he has done this in the service of reactionary political objectives.

One point that is worth clarifying, for those who can’t manage to read Derbyshire’s full article, is that the reference to Anand making a claim of ‘medical certainty’ relates to testimony given in New York in which he stated under oath that:

‘I can state my opinion to a degree of medical certainty that all fetuses beyond 20 weeks of gestational age will experience severe pain by the partial-birth abortion procedure.’

In citing ‘medical certainty’, Anand is not indicating that he is making a statement of fact or even a statement which should be considered scientifically valid. Medical certainty – or ‘reasonable medical certainty’ as its more often expressed – is a purely legalistic terms which means only that Anand is giving nothing more than his opinion as a doctor and backing it up with the authority of his professional status and standing, against which one might reasonably cite an alternative interpretations for the term provided by Peter W Huber, author of ‘Galileo’s Revenge, Junk Science in the Courtroom’ who points out that:

a physician holding the M.D. degree is permitted to testify to anything, so long as he is “willing to mumble some magic words about ‘reasonable medical certainty.

Before noting the practice provides ample opportunity for what he derisively the

the potential for malpractice by mouth.

While James E. Hullverson, Jr., of the St. Louis bar has noted that

the phrase has been a source of confusion, frustration, and endless interpretation for litigants, trial judges, and appellate courts

and expressed the view that

the “‘reasonable certainty’ shibboleth makes the expert witness the evidentiary gatekeeper of his opinions.

In short, it amounts to no more than ‘Trust me, I’m a doctor’.

In her own follow-up from the meeting, in which she notes that Derbyshire did attend to pose a question from the floor, Dorries makes the following observation (after first making a show of citing Anand’s professional credentials):

It might be worth mentioning here, Derbyshire, who challenges men with the stature of Professor Anand, is a Psychologist.

I am one of those people – in common with most – who understand their own limitations; it’s a lesson Derbyshire, certainly judging by last night, has yet to learn.

Dorries may well claim to understand her own limitations but, frankly, there’s little evidence of that on show in approach to this debate – except, perhaps, in the haste with which she ran away and hid when challenged over her false allegations against Ben Goldacre.

Stuart Derbyshire is not ‘just’ a psychologist – he is a neuropsychologist, a discipline which doesn’t require the ownership of a couch but does require the same degree of medical knowledge and understanding of the brain as an practising neurologist (think ‘brain surgeon’, if it makes the comparison easier) and a senior lecturer at the University of Birmingham, whose academic credentials more than stand up to scrutiny (49 published journal articles cited on PubMed for starters). Moreover, and so far as I can ascertain, while he has published detailed critiques of Anand’s work, in so far as it has been misapplied to the question of abortion, I can find no record of Anand responding directly to Derbyshire’s criticisms, let alone rebutting any of his arguments.

Dorries, as usual, is trying to downplay Derbyshire’s professional standing in order to bolster her own position, in no small part, I suspect, because she lacks the detailed understanding of the issues (and the science) necessary to engage with the substance of the debate at anything other than a superficial level of smears, innuendos and, in the case of Anand, a bit of overblown ‘hero worship’ – by any measure her efforts to present herself as advancing a position founded in science mark her out as nothing more than an intellectual fraud and a charlatan, not that that’s a novel observation.

By way of a final contrast, you may like to contrast Dorries’ adopted approach to this whole debate with this observation (again by Stuart Derbyshire) which neat expresses why I, and many others, find Dorries’ antics so disreputable:

The attempts to make a moral argument through science are deeply concerning. Arguments over life, rights and the sovereignty of a woman’s body cannot be replaced by science dictating the conditions of an acceptable abortion. Such a situation would represent a tyranny of scientific expertise that should be as equally unwelcome to the opponents of abortion as to those who support it.

-------------------------

Share this article

| post to del.icio.us |

'Unity' is a regular contributor to Liberal Conspiracy. He also blogs at Ministry of Truth.

· Other posts by Unity

Filed under

Blog

3 responses in total ||

Bravo for picking through this stuff. Don’t know where you get the resilience. I’m ready to slice open my jugular after about one and a half posts on Dorries’ “blog”.

What interests me is whether she has *any credibility at all* within intelligent Tory circles – what with this charade coming hot on the heels of that hilarious Goldacre thing. I find it pretty shocking that *anyone* in mid Beds would vote for her, let alone enough of them to get her elected (and if that isn’t an argument for STV that ought to appeal to Tories, I don’t know what is…). I have come across plenty of intelligent Right-thinkers in the past – even plenty of perfectly intelligent (though obviously wrong) “pro-lifers”. I’d hate to think any of them would give this muppet the time of day. So, does anyone out there *know* if she has any credible support?

Thanks Unity. The entire episode was extremely frustrating; I would have very much liked to have debated my differences with Anand but that was made impossible by the way Dorries set up the meeting. Originally I expected something academic(ish) but it became increasingly clear that I was being asked to speak at a pro-life rally. I asked Dorries to redress the imbalance in an email sent February 25:

—————————-

Dear Nadine:

I have considered your kind invitation overnight but I remain deeply uncomfortable taking a platform with two clinicians. In order to have a balanced discussion there must be an O&G person on the platform who will balance any comments made by Professor Campbell and any clinical discussion from the floor. Although I can speak with considerable authority with regards to fetal pain I am not able to attain the same authority with regards to viability, breast cancer, suicide, cooling off periods and so on. A clinician will be much better positioned to address these types of concern.

My understanding is that Dr. is prepared to step forward in this role at short notice and I would be comfortable with that.

I would also be happy to consider other potential speakers.

I do hope you are able to accommodate this request as I would very much welcome the opportunity to debate my differences with Professor Anand in public and in person.

Yours truly,

Stuart.

—————————-

Dorries refused so I declined the invite to speak later that day:

—————————-

Dear Nadine:

With much sadness I am going to have to decline your offer to speak. It is not reasonable to have a panel that will be 2:1 against my position, especially as I expect the chair will share their views and not mine. I am not an expert on time limits. Furthermore, the issue of fetal pain, which is my expertise, is barely relevant to the issue of time limits. I am also not an expert on ultrasound, which you state will be part of the discussion. Without somebody who can challenge the speakers on the issue of time limits and the use of ultrasound, the panel will not be balanced. Moreover, if anything is raised from the floor not related to fetal pain, which you agree is likely, I will not be able to answer from a clinical perspective unlike my other colleagues on the panel. The imbalance, again, is very obvious.

If you are happy to have rebuttals from the floor then there is time to make it formal with the rebuttal placed on the platform. The time saved in discussion from the floor can be dedicated to the expert panel. Fifteen minutes per speaker, which is entirely adequate, still leaves 60 minutes for discussion. My understanding is that RCOG will not attend a meeting that is unbalanced in order to rebut from the floor in any case.

I have no option but to withdraw unless the panel is balanced and I will advise RCOG as to my action.

With much regret,

Stuart.

—————————-

I attended the meeting anyway; it is rare that I get the opportunity to see Prof. Anand speak and I wanted to hear what he would say. Dorries began the event by criticising the STC for its bias, incorrectly attacking me for not sending written evidence to the committee (I did) and criticising the STC for having me give oral evidence anyway (I didn’t). The subsequent fawning over Anand and Campbell was gratuitous.

Anand began his presentation by restating that he has no philosophical attachment to any pro-life or pro-choice position. A statement I find quite remarkable because it is contradicted by his behaviour and implies that he doesn’t care about abortion, when he obviously does. Regardless, his talk was occasionally interesting but most of it was taken up by self-promotion and multiple slides showing the titles of his published papers. He made dismissive and sometimes incorrect comments about my work as well as those of my colleagues who have also suggested the fetus does not feel pain.

Clearly nobody realised I was in the room and so they felt quite able to launch into a variety of personal attacks and jokes at my expense. Iain Duncan-Smith noted with much humour that I am yet to attain the status of professor. To see my professional colleagues, with their superior academic and clinical status, take part in such silliness was just sad. I can only hope that when Professors Campbell and Anand finally realised I was in the room that they were appropriately embarrassed.

More good stuff Unity. Yes, I do wonder where she gets her credibility from. But then we know certain people are happy to keep promoting bad ideas.

This point:

What Dorries is relying on here to push her agenda is a carefully calculated and contrived ‘wedge’ strategy, which is based on a not unreasonable assumption that many people, especially those with a limited understanding of (and interest in) the complexities of the scientific and non-scientific questions we’re dealing with in this debate, will respond emotionally, and viscerally, to the idea that a foetus may experience pain from a particular point its development and, as importantly, will do so far more than they will to the somewhat more abstract questions of consciousness and that this will, in turn, cause many people to re-evaluate their position on what they see as (morally/ethically) correct upper legal limit on abortion.

You’re right – and I think its also great for us. Nothing like a wedge issue to get your side mobilised and organised and do something. If the Tories can do it, why can’t we?

Reactions: Twitter, blogs

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

You can read articles through the front page, via Twitter or rss feeds.

» Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit

» Why raising taxes is the only progressive way to tackle the deficit

» Why the Zakir Naik ban is wrong

» I didn’t vote Libdems for this

» Shock as council refuses to endorse gay blood donation

» Why we’re making the case against government cuts

» Do the England squad need better incentives?

» Which Labour candidate can social democrats be proud of?

» Is the Telegraph censoring criticism of climate-change deniers?

» Three years on, Israel’s blockade is still illegal

» Did New Labour suffer from a contradiction in policy ideas?

|

32 Comments 96 Comments 13 Comments 14 Comments 62 Comments 21 Comments 22 Comments 11 Comments 23 Comments 8 Comments |

LATEST COMMENTS » Counterview posted on Tories try to rehabilitate disgraced advisor » Bob B posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » sally posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » Bob B posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » sally posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » Bob B posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » blanco posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » captain swing posted on Oona King unveils strong support against Ken » Bob B posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » LMO posted on Why the coalition is swimming in bullshit » J posted on Am I the world's freest woman? » sally posted on Am I the world's freest woman? » Gould posted on Am I the world's freest woman? » Gould posted on Am I the world's freest woman? » Sunny Hundal posted on Am I the world's freest woman? |