Recent Articles

What can we learn from one man’s journey to radicalisation?

What does it mean to be so alienated from civil society that none of the democratic structures available offer an outlet to articulate your anger and frustration? This is explored in Radical: My Journey from Islamist Extremism to a Democratic Awakening by Maajid Nawaz, published in 2012.

What does it mean to be so alienated from civil society that none of the democratic structures available offer an outlet to articulate your anger and frustration? This is explored in Radical: My Journey from Islamist Extremism to a Democratic Awakening by Maajid Nawaz, published in 2012.

It’s worth exploring this question now given the recent killing in Woolwich and the rise in prominence of the English Defence League. The idea that ‘home-grown’ men who have functional lives in the UK and, like the 7/7 bombers, reject the dominant ideology so vociferously that they turn to violent extremism worries many commentators.

Maajid Nawaz was born and raised in Essex. To an outside observer he may have seemed relatively integrated: he enjoyed popular culture, had girlfriends, went to college and had friends. But this only tells part of the story. Growing up he was subjected to systematic racial abuse and learnt to fend for himself and others. The sense of being an outsider and the subsequent feelings of displacement had begun early.

The alienation that Nawaz experiences are a driving force for him becoming radicalised, not dissimilar to the reasons people join far rights groups. In both instances, they feel the only viable option available to them is to join organisations that give them a sense of identity and purpose. The demonisation of the ‘other’ provides an outlet for their anger and frustration.

Maajid Nawaz was politicised at university, being recruited into Hizb ut-Tahrir (the Liberation Party). Using his charisma and rhetoric to recruit other students, he was seen as an early leader. There is a particularly brutal scene when an African student is stabbed to death by another young man who has become radicalised. The fact that Nawaaz and others are able to stay affiliated to such groups illustrates the level and intensity of the indoctrination.

While studying for his Arabic and law degree, he travelled around the UK and to Denmark and Pakistan. He used this as a ploy to set up new cells to recruit other men to the cause and spread an ideology of Islamic extremism. He is later arrested, imprisoned and tortured, and then put in solitary confinement in a Cairo jail reserved for political prisoners.

By the end of this journey he publicly renounces fundamentalist Islamist ideology. He later went on to establish the Quilliam Foundation with Ed Hussain.

Tony Blair has called this a “book for our times”, which “should be read by anyone who wants to understand how the extremism that stalks our world is created and how it can be overcome”. The Labour government was to strongly back the Quilliam Foundation. This explains much of why Nawaz is demonised by some sections of the Muslim community. To be praised by a Prime Minister whose foreign policy has stoked much of the animosity British Muslims may feel, does not lend the author with much credibility within some sections of the Muslim community (and beyond).

However, if Radical provides us with one useful message, it is that it gives us a narrative to understand how important it is to address the alienation that young men (in particular) are experiencing. Without actions to address this, they are more susceptible to join groups which give them a sense of purpose and identity.

But to treat this distinct from other forms of extremism takes away a valuable opportunity for an accurate analysis of the causes of these criminal acts. It also fetishizes Muslim extremists unhelpfully and lends itself to further stigmatising Muslims within the media. This is often followed by a rise of Islamaphobic hate crime which feeds into greater levels of alienation by those being victimised. And so the cycle goes on.

—

Amazon.co.uk: Radical: My Journey from Islamist Extremism to a Democratic Awakening

A call to arms on International Women’s Day

I am not often filled with rage but earlier this week I attended a screening of ‘Banaz: a Love Story‘ directed by the Human Rights activist, Deeyah, and I felt such frustration and anger.

We hear statistics about the numbers of young people, mainly women, experiencing so-called ‘honour’ based violence and oppression but watching this young woman, who was eventually murdered by her family members, gave a stark insight into the horror of what these young people, mainly women, are enduring on a daily basis.

The figures for domestic violence in the UK are harsh, make no mistake. The Home Office reported that in the UK 1 in 4 women will suffer domestic violence in their lifetimes and the Home Office reported that in 2010/11, 21 men and 93 women were killed by a partner, ex-partner or lover in the UK.

The Forced Marriage Unit published its figures this week indicating that they gave advice or support related to a possible forced marriage in 1485 cases involving 60 different countries across Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Europe and North America last year. Of the 744 cases where the age was known, over 600 of those involved were young people under the age of 26.

What I saw on screen a young woman fighting for her life. She fought time and time again. Her father sought to break her will and her spirit. This is exactly what this hate crime – because it is a hate crime – seeks to achieve. There is an intense hatred and fear of women: their autonomy, their sexuality, their intellect, their very essence.

She was mutilated at a young age so she would derive no pleasure from sexual activity; as she grew older she was not allowed friends as they would be a negative influence on her; when she turned 17, her father and uncle arranged her married to a much older man from Iraq who spoke no English and abused her in every way imaginable: sexually, physically and mentally.

When asked why he raped her repeatedly, he had responded, “well I only do it when she does not want to have sex.” When she left him, the men in her family forced her to return to retain the honour of the family within he community.

It is the very people that should be your support and provide you with love and care that sometimes put you in harms way. A form of collective madness overtakes a community and their traditions, culture and social mores provide moral legitimacy for their actions.

Banaz was savagely raped and murdered by her cousins, as planned by her uncle and father. Like in other cases we are only too familiar with – Shafilea Ahmed, for example – no one in this community provided protection for these young women. The silence of the community leaders in these horrific cases is deafening.

In Banaz’s case, the report from the initial interview did not even get written up until three months later. She approached the police time and time again and at one point left a note with the names of the people that would kill her; tracking those individuals helped them to eventually find her body.

We need a call to arms on International Women’s Day. We will fail time and time again if we don’t get this right.

The End Violence Against Coalition is proposing to make Sex and Relationships Education statutory to deal with this problem because schools have a vital role to play in helping young people develop healthy attitudes and behaviours, as well as supporting young people experiencing abuse.

Karma Nivarna have tried countless times to go into schools and raise awareness about forced marriage and honour based violence but are turned away because schools want to bury their heads in the sand.

During this month of activity to celebrate women, we have must show dogged determination and be resolute to stop violence again women and girls.

What does My Mad Fat Diary tell us about mental illness?

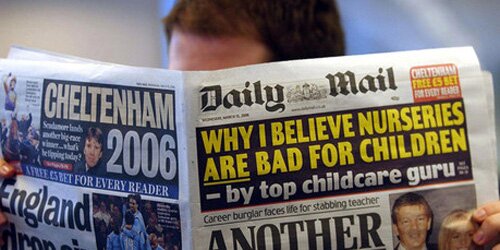

To state that there is stigma and ignorance about mental health is an understatement. The media portrayal of mentally ill people is often in the context of extreme instances of violence and social disorder.

This continues to stigmatise mentally ill people and does nothing to raise awareness of their everyday struggles and the work they have undertaken to overcome moments of debilitating mental anguish. It also paints an unbalanced picture to the public. Disabled people are much more likely to be victims of hate crime, rather than being the perpetrators.

This week was a quietly successful day for campaigners that have advocated for this stigma to be challenged via a change in the law. The Mental Health (Discrimination) Bill 2012-13 was passed by both Houses of Parliament and now awaits Royal Assent to enable it to be passed onto the statute.

The aim of the Bill is to reduce the stigma and negative perceptions associated with mental illness. It would repeal legislative provisions that can prevent people with mental health conditions from serving as Members of Parliament, members of the devolved legislatures, jurors, or company directors. It says much about the attitudes towards those people experiencing mental illness that such a law is even required.

The evidence indicates that disability discrimination is rife. The Equality and Human Rights Commission investigation into disability hate crime states: “in the worst cases, [disabled] people were tortured, apparently just for fun. It’s as though the perpetrators didn’t think of their victims as human beings. It’s hard to see the difference between what they did, and baiting dogs.”

For people with mental illness the stigma of engaging in anti-social behaviour is a common one in the mainstream media. However, this representation is disproportionate and does not do anything to shed light on the extent to which mentally ill people experience hate crime themselves.

In its response to the EHRC consultation on disability harassment, the mental health charity Mind states: “since one in four people experience a mental health problem during their lifetime, and the vast majority of these people face crime and victimisation, clearly disability-related harassment is a significant problem for people with mental distress.”

In light of all this, and as someone who has personally experienced severe bouts of mental illness, it has been refreshing to watch My Big Fat Diary for people to get a real sense of what it is like to recover from a breakdown.

What I find particularly poignant is the struggle the lead character, Rae, has after her breakdown to rebuild her life and that desperate need we all have to lead a ‘normal’ life. This involves boyfriends and her navigating a complicated relationship with her mother. This is against a backdrop of flashbacks which triggered her mental anguish as well as the snatches of conversation we witness she has with her therapist. The latter is painfully accurate. The therapist gently pushes her to confront her past and that trigger situation which led to her hospitalisation.

I don’t recall watching such an accurate portrayal of mental illness before and I welcome it now in the hope that it raises awareness. I also hope that when the Mental Health (Discrimination) Bill becomes an Act of Parliament we can begin to engage in a more fair and open dialogue and process to ensure mentally ill people are not discriminated in public office.

However, remembering that one in four people will experience some form of mental illness in their lifetime, it is about time that we begin to properly support those people experiencing depression, anxiety and all the other multiple forms of mental illness that can be so truly debilitating.

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE