Recent Articles

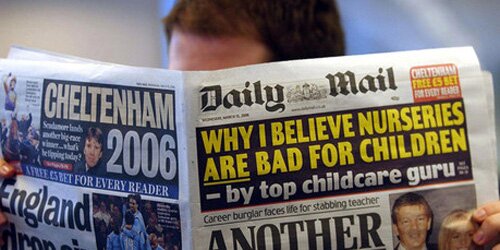

How the Daily Mail twisted housing statistics to blame immigrants yesterday

The Daily Mail have managed again to combine two of their obsessions, migration and housing.

In a highly misleading article last week that suggests migrants are preventing existing residents from getting social or council housing.

Luckily the Financial Times has journalists who know how numbers work and don’t trade in scare stories – I am indebted to @StatsJournalist Kate Allen for alerting me to the data behind Steve Doughty’s nasty little piece.

The claim is that nearly 500,000 council homes (the article clarifies in the text that this includes all social housing) have been allocated (“given” is the term inaccurately used) to “immigrants” (although as Kate Allen points out, the data relates to people born abroad, which stretches from Boris Johnson to many children of armed services personnel) in the past decade.

The real story about housing and migration is this. People born outside the UK are much more likely to live in rented accommodation than people born here, because they are poorer.

Of those living in rented accommodation, most people born abroad are in the less beneficial private rented sector. And what we need to ease the waiting lists for social housing isn’t less immigration, it’s more social housing – we need to build more homes people can afford.

The Mail doesn’t point out that seven times as many people born in the UK live in social housing as those born outside, nor that the predominant form of housing tenure for those born in the UK (33 million to 15 million) is home ownership (among those born abroad, the ratio is 3 million to 4 million – they mostly rent.) One reason why people born outside the UK are more likely to be in social housing than people born here is because they’re poorer, and that’s why they concentrate in the least advantageous forms of housing. There are ten times as many native-born homeowners than foreign-born, eight times as many social renting natives, and just over twice as many native-born as foreign-born private tenants.

It’s also worth noting that the more recent the arrival, the more likely foreign-born people are to be private tenants. two thirds of those who arrived before 1981 own their homes (surprisingly similar to the domestic population), but nearly two thirds of those who have arrived since 2001 are private tenants. One in seven recent arrivals are in social housing, compared with one in six of the native born (again, exactly the same proportion for those who arrived before 1981). Not surprisingly, the longer people live in the UK, the more they behave just like those born here.

However, in one of those ironies of right-wing populist politics that gets people at the Mail chewing the carpet, part of the crackdown on immigration that the coalition Government is presiding over – by making private landlords less likely to rent to migrants – will force more recent arrivals into homelessness, thus triggering the requirement on local authorities to provide them with social housing. So a direct result of the Government crackdown on immigration will be an increase in the proportion of social housing going to migrants!

Osborne’s much derided English requirement for immigrants is only about scapegoating them

One of the nastiest pieces of George Osborne’s Spending Round last week was his announcement that benefit claimants who refused to improve their English to find work would be penalised.

Nasty not so much because of its likely impact on unemployed non-Anglophones, as because he was giving a high profile to a problem which doesn’t really seem to exist.

As several people have pointed out, this isn’t sensible welfare strategy, it’s pure dog whistle anti-immigrant politics: 87% of those polled were reported by the Telegraph to back the utterly imaginary crackdown. We’re with the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) who said:

“To make unfounded statements that portray migrants in a negative way is not only discriminatory but chips away at social cohesion and will only serve to create tensions in our society.”

The Spending Round 2013 document spells it out:

“all claimants whose poor spoken English [I’m not sure how significant the omission of written English is] is a barrier to work to improve their English language skills, with claimants mandated to attend English language courses and sanctions for those who refuse to participate.”

It will be interesting to see, when detail becomes available, how much this measure is intended to save. But as Channel 4′s fact checker pointed out, benefit claimants already face English tests, and if their language skills aren’t good enough, they are offered free English lessons currently costing the Treasury £50m a year, and if they don’t take them up they face the benefit curbs Osborne says he will introduce in 2015.

Ellie Mae O’Hagan, meanwhile, pointed out in the Guardian that her experience of working for Unite, organising migrant workers in London’s East End, suggested that people are keen to improve their English, contrary to what Osborne implied. Indeed, the cost to the Exchequer of teaching English as a Second Language (ESOL) has been cut from £300m to the current level, leaving many keen learners unable to access courses unless they can pay for it (which wouldn’t include benefit claimants.)

—

We’ll be discussing the part rhetoric is playing in the politics of social security cuts and the need for solidarity at a seminar on Solidarity and Social Security Cuts on the afternoon of 24 July. The speakers will include Alison Garnham of the Child Poverty Action Group and Professor Ruth Lister, from the Labour front bench in the House of Lords. Plenty of time has been allowed for discussion and debate. Places are free, but please book in advance.

Don’t blame consumers for the Bangladeshi factory disaster – blame multi-nationals

Ever since the disaster at the Rana Plaza textile factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, some commentators have been trying to guilt-trip cash-strapped western consumers for the terrible conditions of workers in Bangladesh’s Ready-Made Garment (RMG) sector, where wages are as low as £27 a month.

We’ve been told that our insatiable desire for cheap clothing is what keeps wages down, and working conditions so poor that factory fires are endemic and corners cut so badly that buildings collapse, as Rana Plaza did.

But we think cash-strapped consumers aren’t the problem, and the TUC have researched and published a quick graphic to explain:

The suggestion that consumers are to blame struck us as a bit too convenient. So we asked the textile unions in Bangladesh how much their members were paid to make a t-shirt.

Believe it or not, there’s actually a term for how long it takes a textile worker to run up a basic t-shirt: the ‘Standard Minute Value’ or SMV. And the time it takes is 10.565 minutes. That’s a rough estimate, presumably!

Textile workers usually work over 200 hours a month, producing nearly six t-shirts every hour. So the princely wage they receive for each t-shirt is roughly 2p. We’ve found costs in high street shops ranging from £2 to £10, with the archetypal t-shirt mentioned in several reports costing £6.

So the price you’re charged for a t-shirt has nothing to do with the wages of the textile workers who made it. To double their wages would increase the production cost of a basic high-street t-shirt by 2p.

That all suggests that someone’s trying to pull the wool over our eyes about who’s really responsible for the low wages and poor health and safety standards in Dhaka’s RMG sector, and it’s the global brands and manufacturers who set the prices.

Bizarrely, some of them have insisted that they have no control over wages, hours of work, factory safety and the like. But they can determine the time it takes to manufacture a t-shirt down to three decimal places and determine what the stitching on the hems looks like! Pull the other one!

We’re supporting the global union for textile workers, IndustriALL, who are demanding that global brands, retailers and manufacturers sign up to an agreement on health and safety and wages. You can support them by by taking this e-action.

Crucially, workers in Bangladesh need the right to join a union and the right to negotiate terms and conditions with their employers. But they also need to work in safety, as the International Labour Organisation has insisted.

The people who should be feeling guilty are the people who run those global multinationals and the Government of Bangladesh. Not shoppers like you, struggling to get by on wages that are also not increasing, while the costs of food, fuel and accommodation continue to rise.

Workers everywhere need dignity at work, based on decent wages and decent jobs.

Only the City-backed Tories oppose the Robinhood Tax

Yesterday, senior Liberal Democrat Minister Vince Cable went beyond Government policy in backing the Robin Hood Tax to crack down on short-termism. He told a select committee:

“I have got no objection to the… well, I would put it more positively – I think there is a case if you are trying to change behaviour from using a market instrument of that kind to make it happen.

“I think there is a case and I’m in some ways quite disposed to it.”

The immediate slap down from anonymous Treasury sources – they said he wasn’t responsible for tax policy – shows how important Vince’s statement is.

As Business Secretary, Cable is ideally placed to see the damage done to the real economy by the high frequency trading and speculation that dominates the finance sector.

TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady said:

“Most European governments – apart from our own – can see the value in a Robin Hood tax on the banks’ financial transactions and a cap on the sky-high bonuses they’ve been awarding their senior staff.

“We welcome the Business Secretary’s acknowledgement that there is a case for a financial transactions tax and hope that some of his more sceptical colleagues may soon realise its worth too.

“The banks helped make the mess we’re in, yet it’s ordinary families who are paying the price. A tax on the banks would raise much-needed revenue for the Exchequer and hopefully persuade ministers that the time has come to put austerity economics back in its box.”

Vince was also backed by Simon Chouffot, spokesman for the Robin Hood Tax campaign, which represents organisations including Barnardo’s, Oxfam and Friends of the Earth as well as the TUC, who said:

“It’s good news that Vince Cable has broken ranks with his Cabinet colleagues over the Robin Hood Tax.

“As Business Secretary, he should know better than most that defending the City fat cats is bad for Britain and bad for business. The banks are protecting the status quo of gambling and bonuses at the expense of investment in jobs and growth.

“The Government should drop its ideological opposition to a tax most voters back, and make sure Britain gets its fair share of the European FTT to help protect public services and rebuild our economy.”

A statement like this from a senior Liberal Democrat politician – in line with Labour Leader Ed Miliband’s call for responsible capitalism – adds to the tension in the coalition.

In most European countries, the Robin Hood Tax is supported across the left and the centre-right, and that could spread to Britain, leaving the City-backing Conservatives isolated again.

Labour pushes Democrats for a Robinhood Tax

I’m back from a 48-hour round trip to Washington DC with Shadow Financial Secretary to the Treasury Chris Leslie MP, and it was really interesting to see exactly the same debates about a Robin Hood Tax being had in the USA as we’ve had in the UK.

EU Tax Commissioner Algirdas Semeta spent longer in the US, making the case for the 11-country EU financial transactions tax in New York as well as Washington.

The two visits were designed to promote the EU transactions tax in the US, and inch both the US legislature and executive, and the UK, towards joining the EU’s initiative, so it’s good news that this week, Senator Harkin and Rep deFazio are re-introducing their “Wall Street Trading Tax” in Congress.

Their letter to other members of Congress seeking support for the tax quotes Nobel prize winning economist Paul Krugman and AFLCIO President Richard Trumka, but also former Chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Sheil Bair and John Bogle, the founder of Vanguard, a huge mutual fund company.

Signs of support for an FTT are growing – the H-street based Center for American Progress itself, very close to the Obama White House, has never been so forthright in support. Commissioner Semeta said that when he had been in New York, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon had expressed his support for the tax, and Wall Street bankers had been interested more in the rate than opposing the principle of the tax.

Chris Leslie’s presence was designed to open up a dialogue between the Labour Party and Democrats about how to co-ordinate their work on the issue, to deal with concerns about tax competition between Wall Street and the City of London, although such competition is more apparent than real, given the possibility of designing FTTs to prevent avoidance by moving jurisdiction.

There will be more transatlantic discussion as a result of his visit.

Chris Leslie recorded this interview after the seminar at which he spoke:

He said: “I don’t see any evidence that there would be a negative effect on economic growth. In fact, quite the opposite. I think if you did have a global financial transactions tax where all of the global financial centers were involved and it was also set at a rate that is pretty modest, it wasn’t going to have a distorting negative consequence, then you could raise revenues that would actually help promote growth and invest in job creation. And I think ultimately that’s one of the main arguments in favour of a financial transactions tax.”

Is George Osborne serious about tackling tax-evasion too?

George Osborne wrote an article for the Observer yesterday committing to multilateral action against tax evasion and claiming to be leading G20 finance ministers in a new initiative.

Along with reiterating his pledge to meet the UN target for overseas aid in the coming tax year, he opposed multinational corporations dodging their UK taxes by shifting profits overseas, and also opposed the way they do the same – with even worse impacts – against developing countries.

It may seem churlish not to welcome the repentance of such a serial sinner (he’s still cutting the UK’s corporate tax rate, and has refused to u-turn on the decision to cut the top rate of income tax, remember.) But is this really the same politician who has refused to join – and tried unsuccessfully to scupper – the European Robin Hood Tax on financial transactions? It surely is.

There’s a possibility that Osborne really is fed up with the way Amazon, Google, Starbucks and the rest have tried to avoid paying UK tax. And it’s also possible that Osborne is trying to claim credit in the UK for a move portrayed in other countries as an EU initiative led by the finance ministers of France and Germany, as well as the UK: the leg-work for this initiative was done by the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

It would be easy for Osborne to dodge the argument that he might start out by addressing the problem caused by the tax havens the UK oversees: he will simply claim that the only way to defeat tax arbitrage is by a global agreement rather than unilateral action.

Although if he’s such a committed multilateralist all of a sudden, that refusal to endorse multinational action on transaction taxes (to defend the City of London, he says) looks harder to explain.

And his lacklustre crack-down on giving public contracts to tax avoiders (he’s so committed to this that he’s letting them carry on securing contracts in the health service, education, local government; and all they have to do is swear they never, ever did anything naughty to escape the crack-down…) does not inspire confidence either.

Nor does the omission of tax dodging from DFID Secretary of State Justine Greening’s recent panegyric to the private sector….

So, all in all, underwhelmed is how Osborne’s startling conversion to global tax justice leaves me. But let’s look on the bright side, and wait to be impressed. We will watch the space where action against tax havens and tax avoiders should appear.

Three ways we could have more radical, progressive international development

On Saturday I spoke at the University of Newcastle’s excellent International Development Conference (#IDC2013) about Progressive Development. Below is an edited version of my remarks.

My main argument was that changes in the global economy were making traditional approaches to development – which portray the economic issues facing emerging and developing countries as qualitatively different from those facing industrialised nations – less relevant.

1. Development isn’t different

It’s often said that the past is another country, and that’s an important issue in international development. In the 1930s, my uncle and aunt were domestic workers; my grandad was a street vendor. Both occupations are key elements of the informal employment that characterises so many poor communities in the global south.

But of course they were in Plymouth and Cardiff, and within a decade they were all in regular employment, with pensions, a National Health Service, and a home of their own. They were also paying income tax, which was a major change.

Seemingly intractable poverty can actually be overcome remarkably quickly. Even in Europe, we only made poverty history recently, and it may be on the way back.

What I take from this is that the challenges of international development are not so different from the challenges we face in our own country.

This morning’s Action Aid report about tax dodging by Associated British Foods in Zambia is not so different from last year’s domestic scandals about Amazon, Google and Starbucks. Tax justice is a global agenda, not specifically a northern or southern problem.

Another example is Oxfam, founded 75 years ago to mount famine relief programmes not in Africa but in Greece. We may even have come full circle with the expansion of food banks even in Britain.

When Make Poverty History was launched in the UK in 2005, it was about poverty in developing countries. But others did it differently. Make Poverty History Canada addressed domestic poverty as well.

2. Solidarity isn’t charity

I don’t agree with those who say that overseas aid is a bad thing, encouraging dependency. I see it more as a form of economic transfer payment like unemployment benefit. State expenditure has been vital to the economic development of industrialised countries and spending on education, health and infrastructure is as vital in developing countries as it is in the north.

But at the same time, unemployment benefit is only a sticking plaster to get people through the bad times, until economic growth returns. So I’m pleased to see politicians starting to talk about ending aid in our lifetimes.

China, for example, is the major success story in reducing the number of people in absolute poverty, and that’s been achieved through a mixture of economic growth and welfare safety nets, rather than external aid.

But what I particularly take from the Chinese model is that, primarily, you cannot eradicate poverty from outside: the people who will overcome poverty are the poor themselves, and our role is to support them in that rather than take over and do it for them.

We can certainly stop making things more difficult – for example by ensuring that multinational corporations don’t dodge their taxes, and adhere to international labour standards.

And we should certainly stop portraying people in poverty as powerless victims: the ‘starving black baby’ pictures that open people’s purse strings, but don’t challenge the fundamental causes of poverty here or abroad.

Indeed, we should take our lead from those who are demanding change, rathe than imposing our own model on them. That’s frankly the TUC’s main concern – among rather too many to be comfortable with – about this year’s ‘Enough IF’ campaign, which was developed without any southern leadership or even input at the planning stage.

3. We need a new model of development

So, the concluding point I would make is that we need a model of development campaigning that addresses issues that affect people across the globe: tackling inequality between and within countries, reconciling economic growth with environmental sustainability and social justice, that says saving a hospital in Lewisham is as important as opening one in Luanda.

Tax justice is easily the clearest example of this, but precarious employment and informalisation is a challenge in the USA and Southern Europe just as it is in Ghana and Nigeria. Violence against women is an issue affecting the UK with cuts to police domestic violence units and Women’s Refuges, even if South Africa, India and the DRC present more alarming news.

So we need development initiatives that span the G20 and the G77, campaigns that are led by southern as well as northern voices. Inequality has been thrust into the forefront in industrialised countries, and in particular the shift in extreme poverty from poor countries to middle income countries.

These are the issues that will condition the post-2015 agenda, rather than the largely technical issues of the MDGs.

And this is especially important in conditions of economic hardship in the industrialised world when the pressure on politicians and on civil society generally is to focus inwards. Because charity isn’t enough to change the world.

Are Labour finding a radical and progressive vision for international development?

Labour Shadow Secretary for International Development Ivan Lewis made an important and very welcome speech on international development on Tuesday, about what we should be aiming for once the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) expire in 2015.

It is worth a deeper look, as it sets out a far more strategic vision than his similarly good Party conference speech.

The core of his message was that:

The new framework needs to be values led, rooted in social justice including reducing inequality, sustainable growth and good governance practiced by all development actors. Our overarching aims should be clear and measurable.

By 2030 to have eliminated absolute poverty, begun to reduce inequality, protected scarce planetary resources and ended aid dependency. Ending aid dependency is the right objective for greater equality and the dignity, independence and self determination of nations and their citizens. It should be a core part of the mission of Centre left development policy.

He called his approach a new ‘social contract without borders’ to replace the existing MDGs and the speech is full of commitment to decent work, more jobs, better wages and what is essentially a welfare state approach (eg education, health and sewerage) to international development.

He was even good enough to mention the Robin Hood Tax as one of the innovative possible sources of funding.

He returned again and again to the issues of jobs and tackling inequality, and an international development policy centred on those two themes would I think be both popular domestically and effective abroad.

It would be a good summary of a decent social democratic policy for the UK as well, and he and his shadow ministerial colleagues stressed that much of what they were calling for internationally was similar to what Labour is in favour of domestically.

As well as his support for decent work and living wages, he had relatively sharp words for business, calling for ‘responsible capitalism’. And, unusually for politicians these days, he was quite specific about what that meant. Companies that don’t abide by the principles of decent work and sustainable growth shouldn’t get DFID contracts, and all government procurement should be on that same basis.

Criticisms? Well, there were some quiet intakes of breath from the audience about his suggestion that we should end absolute poverty and end aid dependency by 2030. I’m with him on that (at least as a starting point for debate): if we’re going to set targets and outline visions, they should be challenging. How much absolute poverty would we be happy to see around the world by 2030? How much aid dependency would we be happy with?

—

A longer version of this post is at the Touchstone blog.

The IF Campaign is important but the TUC is not signing up to it

It’s undoubtedly unfortunate timing that British international development charities chose yesterday for the launch of their new campaign which has coincided with the Prime Minister’s big speech on Europe.

The IF campaign is being run by a group of charities with which the TUC and unions have worked closely for years. We co-operated over Make Poverty History in 2005, helped run the Put People First campaign around the G20 in 2009, and we’ve been working for three years on the Robin Hood Tax campaign (all three of these were broad coalitions that went beyond the international development community, with green groups and unions playing a leading role, while IF is a rather more sector-only campaign.)

Many of the specific policy demands of the IF campaign are ones the TUC agrees with, such as legislating for spending 0.7% of Gross National Income on overseas aid; tackling tax havens; and making transnational corporations act openly and honestly.

So I should perhaps explain why the TUC isn’t part of the IF campaign. It’s because there are too many “buts”. Here are three.

One big ‘but’ is that the IF campaign wants global hunger to be the big campaign of 2013, focusing in particular on the G8 leaders’ summit being hosted by David Cameron in Northern Ireland this June. Unions agree that hunger is a big issue and a terrible tragedy (it’s part of the manifesto global unions have issued at the Davos World Economic Forum this week.)

But this year, we think the priority should be fighting the austerity that G8 leaders like David Cameron are forcing on their own people and also on the rest of the global economy (this week the ILO revealed that only a quarter of the rise in global unemployment in 2012 had been in the industrialised world – three times as many were thrown out of work in developing and emerging economies.)

Secondly, the IF campaign has identified four key areas for the campaign – aid, tax, transparency and land. But they haven’t addressed one of the main causes of hunger, which is poverty, both at home or abroad. The world produces enough food for everyone to be fed, but too many people simply can’t afford it, and that applies (albeit to a lesser extent, and rarely to the point of starvation) in developed economies like Greece and, yes, even in Britain. Oxfam was started 70 years ago to help feed the hungry in Greece under Nazi occupation, and they have done fantastic work to highlight the scandal of how many people in Britain rely on food banks. People in Europe go hungry because of poverty and unemployment, and in reality the same issues apply around the world, even in famine-hit countries in Africa. But the IF campaign doesn’t cover this crucial issue.

And thirdly, well, we would say this, wouldn’t we? But what about the workers? The campaign focuses on defending smallholders against corporate land grabs, which is fair enough. But it has little to say about the millions of people who are employed in the food industry, not just growing food but processing and distributing it, including the many smallholders who supplement the produce of their own land with work in part-time or seasonal employment. As long ago as 2005, 40% of the 1.1 billion agricultural workers were employed. Decent work in rural areas is obviously a key element in ensuring people have the income necessary to support themselves, as well as pay for social protection, public services and so on, and decent work is the only sustainable route out of poverty, where aid is often only a sticking plaster solution, vital though it is.

Overall, unions are also concerned about the lack of southern voices leading the campaign, and we’re concerned that a campaign that focuses on hunger – despite the underlying demands that go much further in challenging the way the global economy works – will merely reinforce popular images of starving African babies, and reinforce popular misconceptions that people in the global south are powerless victims and that endless charity is the only solution.

So, while we will work with the IF campaign on specific elements of their campaign, the TUC won’t be signing up, and we’ll continue to argue the case for tackling inequality and injustice globally, at home as well as abroad.

Britain’s problem isn’t EU regulation but productivity and investment

Before we heard the Prime Minister’s Amsterdam speech was cancelled, the TUC issued a press release on what we expected to see in it about the Working Time Directive.

The extracts from the speech that I’ve seen so far don’t specifically refer to it, although they do say Europe must become more competitive, and they suggest he was going to repeat calls for elements of the European social model to be repatriated. Clearly code for allowing Britain to scrap the Directive the coalition most loves to hate.

We wanted to draw attention to the irony of delivering that speech in the country which more than any other demonstrates that cutting working hours doesn’t make a country uncompetitive. Indeed, the Netherlands suggests that the opposite is the case.

The average Dutch worker can knock off an hour earlier every day than their British equivalent, and still produce more for the country’s GDP figures. Dutch productivity per working hour is nearly 30% higher than in Britain (thanks to the TUC’s Paul Sellers for digging these facts out of the OECD statistics.)

It isn’t the Working Time Directive that is holding Britain’s workers back (it’s actually very flexible, as my former boss Lord Monks pointed out yesterday), it’s the lack of training, infrastructure and investment.

And indeed it may even be the long working hours themselves that are the problem. Investment can be a bit expensive, especially up front, so if your workforce is low paid and insecure, it may pay to just make them work longer hours. But insist those hours come down without loss of pay, and suddenly that investment looks more attractive.

One economist recently argued that it was comparatively higher pay in the UK that led to the industrial revolution happening here first, where mechanisation was the cheaper option, rather than in poverty-stricken China where working the population harder was the cheap option.

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE