Recent Environment Articles

The Green Party has abandoned its key principle in support of Scotland’s YES campaign

I’ve not waded that much into the debate on Scotland’s future, partly because I’ve been focusing on ISIS and partly because its not my fight. I support the Union but its up to the people of Scotland to decide and they’re unlikely to be persuaded by this random guy from London.

But I’m perplexed by the pro-independence position that some lefties have taken, particularly the Green party.

The Yes Scotland campaign say their economy is strong and can survive independence thanks to natural resources such as oil and gas. Its a key claim on their website and its true; oil and gas would be key to an independent Scotland’s finances.

Revenue from oil and gas is also how an independent Scotland will pay its bill and stave off deep spending cuts. I’m not saying they’re the only source of revenue but they’re very key to Scotland’s future. Without them there would be deep cuts. Independence would make Scotland even more dependent on that revenue.

As you can see from the chart above, revenue from fossil fuels easily dwarfs everything else combined.

Scotland wants to invest in renewable energy, but the money for investment will inevitably have to come from further investment and money raised through oil and gas.

AND YET – one of three key principles of the Green Party is to reduce “dependence on fossil fuels”. Scottish Greens too say they want to reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

So why are the Green Party supporting an outcome that makes a nation even more dependent on exploiting its oil and gas resources?

Can someone explain this to me?

If the Greens are arguing that Independence will make Scotland less dependent on fossil fuels, I’d like to see the evidence and sums, since the YES campaign in Scotland isn’t saying that at all.

What the media should remember on climate change and the IPCC report

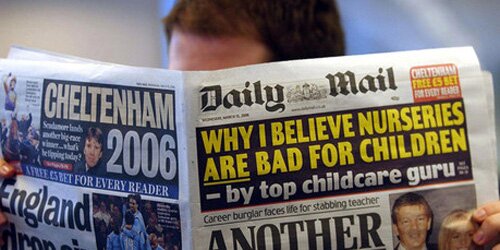

When the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report is published this week, most UK media coverage will be along the lines of:

Scientists say humans are almost certainly responsible for climate change and the world is on course for unprecedented warming over the next century. But the report reflects a gap between scientists and the general public, with growing numbers saying they don’t believe what scientists tell them about climate change.

If anyone doing interviews about the report is daft enough to be reading this blog, there are a few points I would suggest making.

1. The overwhelming majority of the country do believe climate change is real and the world needs to act to stop it.

Around 9 in 10 people think that climate change is happening – only 6% think it’s some kind of conspiracy*. And only 13% – fewer than one in seven people – say it won’t be a threat to Britain.

To put that in perspective, 18% say they want to get rid of the Queen and make Britain a republic: hardly a mainstream view, yet more popular than climate scepticism.

Those numbers haven’t really changed for the last four years**.

2. The report tells us in more detail, with more confidence, what we can expect to happen as a result of climate change

The two most important climate risks for the UK are flooding and summer heatwaves.

The floods in 2007 are estimated to have cost the economy £3.2bn pounds.

We usually don’t think about heatwaves as a bad thing, but the heatwave we had in August 2003 killed over 2,000 people.

Both heatwaves and floods are predicted to become much more common and more severe.

There are still uncertainties. Science by its very nature is never final and certain. But we know enough now to act.

At this point, you may be tempted to talk about how many degrees the world is projected to warm by. Don’t. 4° warming may sound terrifying to you, but it sounds fine to most people.

3. The question is no longer whether man-made climate change is happening. The question is now: what are we going to do about it?

Countries around the world have pledged to reduce the emissions that cause climate change. Even the countries that have traditionally been slow to act – like China and America – are now saying they will cut back their carbon pollution.

Getting these pledges is an important start, but the world needs to do a lot more to make them happen. That includes us – the UK’s independent Committee on Climate Change says we’re not on course to meet our commitment to cut our pollution.

And even if the world does cut its emissions, we’re already on course for some global warming. We have to make plans so we’re ready for it.

In the UK lots of people may wonder if their home will now be at more risk of flooding and if they’ll be able to get insurance. Some people may worry about older relatives and the effect of heatwaves on their health.

What are these risks? Is the government doing enough? At the moment we don’t know because the information isn’t public.

This is what we should be talking about – so we can hold the government to account, to make sure it deals effectively with the most important risks, and spends our money well.

* A poll this month from the UK Energy Research Centre put those who say it’s not happening at 19%. A fair bit higher than the 5% above, but still barely a quarter of the number who say it’s happening.

** In fact, they went down a bit and then came back up. But the overall effect is of no change.

David Attenborough and other food facts about Africa you probably didn’t know

by Jonathan Kent

Many, but by no means all Greens are worried about population. It’s a multiplier on many of the problems we face. But it’s a very sensitive subject, as David Attenborough has discovered.

When I heard Attenborough say: “what are all these famines in Ethiopia, what are they about? They’re about too many people for too little piece of land. That’s what it’s about,” I hear the echoes of generations-old, lazy thinking about Africa and Africans summed up in the notion of the White Man’s Burden.

A little while ago there was a row about whether Green World, the magazine for Green Party members, should take an ad from the group Population Matters of which Attenborough is a prominent supporter. I argued, quite vociferously that it should; I dislike any attempt to stifle debate.

The anti-Population Matters lobby, among them Lib-Con regular Adam Ramsay, pointed out that the carbon footprint of a country like Mali is so small compared to Western nations that the population could double, treble or more without having much impact on the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

True, though unless we keep Malians poor or we can roll out clean energy fast that may not remain the case. And every African needs to eat the same minimum as every European, and even people in the rich West can only eat so much. Over-population results in countries hitting a food production buffer long before they hit an energy buffer.

But David Attenborough and others also need to stop blinding ourselves with stereotypes about Africa.

Firstly, in simple terms of density sub-Saharan Africa is far less populated than North West Europe, the Indian subcontinent, China and Japan.

Then, when one looks at which nations import and which export food, an even more interesting picture emerges. Many West and East African nations are net food exporters – Ethiopia included.

What do they export? Well next time you pick up a packet of mange-tout check out its origin. Chances are it’ll come from Kenya along with cut flowers and other products that drink up water and use valuable agricultural land.

Yes, populations outstripping the ability of the land to support them is a problem; but not in Africa. It’s a problem in Japan, and Saudi Arabia and Russia. It’s a problem in South East England and potentially across most of Europe too. But those are wealthy countries, so we don’t tell people there to stop having children.

Africa’s problem, on the other hand, is one of economics and justice; debt, balance of payments, the need for foreign currency and poverty. It’s about foreign governments and corporations (the Chinese prominent amongst them) buying up land because they know that rich nations consume more food than they can.

If only David Attenborough were as knowledgeable about the human as he is about the animal world he might have talked about the Black Man’s Burden – part of which involves feeding Europeans who are quick to advise, slow to listen and who, for the most part, simply don’t seem to care.

—

Jonathan Kent blogs here.

If we want stronger action on the environment, we need to stay within the EU

by Rosie Magudia

Last Friday, the Green Alliance published their review of the three major political parties’ activity on the environment since May 2010. The “Green Standard 2013” makes disappointing reading for all parties – but for none more so than the Conservatives.

On becoming Prime Minister in 2010, David Cameron said he would lead the “greenest government” ever. He described the existence of a fourth, mysterious minster at the Department for Energy & Climate Change, “who cares passionately about this agenda – and that is me, the prime minister. I mean that from the bottom of my heart”.

Yet despite such reassurances, Cameron’s own Chancellor has repeatedly suggested that environmental progress would compromise a healthy economy. Meanwhile, Owen Paterson, the UK’s Secretary of State and political leader on all things environment, has publicly questioned the reality of human-induced climate change.

However, neither the Liberal Democrats nor Labour have come away unscathed either. The Green Standard describes Labour’s failure to lead upon, prioritise, or even propose credible solutions to green the UK economy.

The Liberal Democrats are portrayed as having “no clear vision for the environment” –a portrait which certainly rings true as only yesterday, the Lib Dems backed a motion to support fracking- a fossil fuel industry vociferously opposed by 1000s of demonstrators nationwide, with 67% of citizens preferring to have a wind turbine near their home than a fracking site.

As extreme weather and energy insecurity bear down on our continent, we need someone to lead us to a better place, fast. While British politicians flag, our EU membership may haul us out of the smoggy darkness. The EU’s record on the environment, while not perfect, is often better than Britain’s record.

From addressing carbon capture, to banning bee-harming pesticides, the EU is providing both a platform to debate these issues, as well as leadership in exploring change.

Let’s take fish as an example. In 2005, the Northeast Atlantic was 95% overfished. Recognising the seriousness of the situation, the European Commission tackled the issue head on through determined fisheries management. Today, the same waters are only 39% overfished.

Concurrently, the European policy governing fisheries has undergone significant, progressive reform; a process frequently led, perhaps surprisingly by Richard Benyon, the UK’s Tory Fisheries Minster. A chance on the world stage allowed him to push for positive change, in a way which he’s failed to do at home, as shown by his desultory progress in establishing only 31 of the originally propose 127 marine conservation zones in UK waters.

The possibility to participate, shape and share a common future on issues such as air quality, weather, natural resources and energy security is one that shouldn’t be overlooked by the debate on our membership of the European Union.

The environment is one issue we’re unable to go alone – we need to be in it to win it.

This is how we can convince Britons about climate change

I’ve been arguing for a while that there’s been too little done to explain to the British public why they should care about climate change. If the problem is seen only to affect animals and people in other countries, campaigners will struggle to win mass support for action to tackle climate change. It has to be made real and personal, or many people just won’t care enough.

But that raises a difficult question. If people don’t already think that climate change will affect them and their family, how do you persuade them they should care?

Fortunately, a mega poll by MORI for Defra provides some answers and the starting point for what a campaign could look like.

According to the UK Climate Risk Assessment, the two most important climate risks facing the UK are flooding and summer heatwaves; I will focus on these as the possible bases for a campaign. However, the poll shows a radical difference in how they are perceived.

It won’t come as much of a surprise that most people in the UK think that flooding is the main risk from climate change (bear with me – it gets more interesting).

The chart below shows the proportion who think flooding has already become more frequent and the proportion who think it will become more frequent by 2050 – and the same for heatwaves. Flooding easily wins out:

Perhaps this is a product of how heatwaves and floods are distributed. Different parts of the country suffer floods at different times, and most serious incidents get news coverage – while heatwaves tend to hit the country in one go, so coverage is more concentrated. So floods may just be in the news more often*.

But I don’t think that’s the full explanation, and here’s where it starts to get interesting.

A later question asked respondents to move on from considering the likelihood, and to say how concerned they’d be if the UK actually experienced these changes. The results are similar: far more people would be worried by more flooding – in fact, more people say they wouldn’t be concerned by heatwaves than that they would be:

So, even if a campaign succeeded in convincing more people that, as it were, summer is coming, most people wouldn’t be that bothered by the prospect. The point is superbly encapsulated in ITN’s presentation of the deadly heatwave this summer. A few hundred people may be dying, but overall everyone’s basking in it and generally having a nice time:

I take two main conclusions from this for campaigns about UK responses to climate change.

Firstly, if someone were to start a campaign now about why people in the UK should want action on climate change, the obvious choice would be flooding. People believe it’s already happening, that it’s going to get worse, and that its worsening would be a major problem. While the poll also shows most people don’t think they personally are at risk from flooding, they’re still concerned and there’s nothing else that has so much legitimacy at the moment.

However, this isn’t to say campaigners should forget about heatwaves. Because another question shows that the conjuction fallacy is affecting the results**. The principle of this fallacy is that people often think that a specific condition, described in detail, is more likely than a broader condition, which is not described in detail, but which the specific condition is an example of.

In this case, we’ve already seen that people don’t think heatwaves are very likely. But when you give them more details about what you mean – make it real – by spelling out the impacts of a heatwave, the proportion who think it’s likely becomes much greater. There’s no equivalent change with flooding, perhaps because most people have already thought about what it means:

Even with this effect, heatwaves are still seen as less likely – but the gap is much smaller, and the following question that tests concern about these specific impacts finds no difference between the described-in-detail floods and heatwaves.

So the case may not yet have been won for why people in the UK should really care about tackling climate change, and flooding looks like the strongest ground for developing the argument further, with the potential to be credible and effective. But with some work to demonstrate the connection between the principle and what it means in practice, there’s no reason heatwaves can’t ultimately be part of a campaign as well.

A New Rural Manifesto for Labour: we call for your support

by Jack Eddy

It is uncontroversial to say that Labour lacks rural appeal. Labour’s voice in the British countryside has been inadequate for decades, but has hit a low-ebb in recent years. Even in the suburban and rural areas where Labour was able to gain some traction from 1997 onwards, the last General Election saw a massive swing to the Tories.

And yet, the Labour Party in the past has successfully gone out to the British countryside to court the rural vote and build the foundations of support. Such accomplishments can come again, but we need renewed endeavour and new direction. If this does not change – and we do not instigate that change – some rural communities may not survive these difficult times.

This is why we at South Norfolk CLP call upon all rural CLPs, as well as other interested affiliates, to support us in our call for a new Rural Manifesto – as specified in the proposal officially endorsed by South Norfolk CLP; a Rural Manifesto made in rural Britain, for rural Britain.

Priority should be given to framing policy to reflect the impact on rural communities, on a number of different issues:

Public transport and other infrastructure improvements, as well as rural unemployment and businesses will be an important subject. In the entirety of Norfolk, the 3rd largest county, there is only one late evening bus service. This is not uncommon for rural areas, with negative consequences to regional economies and rural life in general.

Additional aid to the young and unemployed for the purpose of making them as geographically mobile as possible will be hugely helpful to finding employment. A possible solution could be found in providing travel cards to rural unemployed (allowing travel for free or at a reduced rate), who live at least 2 miles from the nearest major centre of employment – valid for use 1 month after finding permanent work.

The NHS is important to us all, but many rural communities are seeing their NHS services disappear as cuts and privatisation begin to take hold, and they are fighting to stop it. One solution to help meet increasing demand, and go some way to solving the unique issues around isolation from services in rural areas, could be to focus on increasing the number of smaller, satellite hospitals that are strategically located around existing central hubs in rural locations. ‘Satellite Hospitals’ would focus on anticipatory care, diagnostic services, as well as urgent accident and emergency admissions, leaving the central hospitals to focus on the more complex and specialised treatments. By dividing up local populations into different catchment areas, it would enhance the experience of patients by offering a smaller, community feel, as well as provide more jobs.

Naturally, properly dealing with Europe and immigration in rural policy is a must. We must explain how businesses, services and local economies in rural Britain depend on Europe and immigration. Many rural businesses rely on European immigrants and the EU enables farmers and horticultural businesses to trade easily with the mainland (in either goods, equipment or expertise). Many rural businesses could not survive without immigration or the EU in general. Labour needs to illustrate how jobs held by British workers would cease to exist if Britain exited the EU.

However, this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what needs to be covered in a Rural Manifesto – and it is up to us all to decide what must be covered.

To do this, we need you to get our Motion passed in your CLP and submitted for the upcoming Labour Party Conference by 12 noon on Thursday 12th September. We also invite you to contact all whom you feel will be interested, so that we can reach everybody that can help us succeed in this enterprise.

—

If you are interested and have the time, please contact me at and I will send you the proposal for the Rural Manifesto and South Norfolk’s Motion to the Conference.

Anti-Fracking protestors need to be much better at getting their message across

On my way to work on Monday I was curious to see a small group of anti-fracking protesters superglued to the entrance of Bell Pottinger, the PR firm used by energy company Cuadrilla.

The irony is, better PR is exactly what anti-fracking activists need.

The protesters had brought with them signs bearing the slogan “fracking liars” and various other well-worn puns swapping the word “fuck” for “frack”. But I couldn’t see anything that clearly communicated why they were targeting Bell Pottinger in particular.

Indeed, while the protests gained widespread coverage, there was little in the media that conveyed the activists’ precise beef with Bell Pottinger. Given the natural bias of the mainstream media against direct action, it is vital campaigners do everything they can to get their message across.

According to my friend Helen Robertson, who was reporting from the protests for Petroleum Economist, the activists’ arguments against fracking were largely derived from the film Gasland. Irrespective of the fact the documentary’s assertions have been widely disputed, campaigners would be wise to arm themselves with robust facts and figures as well.

Helen’s main point was that with UK gas production falling, the country is increasingly turning to cheaper and more polluting coal, a problem fracking might address.

When she asked one protester if she knew how much coal Britain uses, the activist replied: “I’m hopeless on facts”.

This is a clear issue for the anti-fracking movement, and protesters in general.

In the age of social media and blogging, when any activist can have a smart phone shoved in their face at any moment and see their words splashed across the internet minutes later, it is even more important for campaigners to turn up to demonstrations equipped with cold hard evidence and the media savvy to communicate it effectively.

I support the anti-fracking movement, primarily because looking to shale gas and oil to plug the energy gap shirks the responsibility to dramatically expand clean renewable energy production. It is here that activists can find their strongest arguments – and no doubt many make them – backed by a wealth of scientific evidence behind the threat of anthropogenic climate change.

Ideology and zeal are vital to any movement, but a heart in the right place is no substitute for a head full of facts to back it up.

If you’re going to superglue yourself to a doorway where you can’t dodge journalists’ questions as easily as greedy corporate bosses hopping into a limousine, make sure you have the answers.

Balcombe is a wake up call for local communities over Fracking

by Philip Pearson

As Caroline Lucas MP was arrested at the Balcombe fracking site (19 August) she spoke of the “democratic deficit” being so enormous that “people are left with very little option but to take peaceful, non violent direct action.”

In 2012 the TUC’s annual Congress opposed gas fracking. Motion 43: “The principle of precaution should be applied when developing new energies and the health of people and the environment should be put before profit.”

And this summer, speaking up for gas fracking, the Prime Minister told the Express, “I want all parts of our nation to share in the benefits: North or South, Conservative or Labour … we can expect to see lower energy prices in this country.”

From Balcombe

But will gas fracking will mean lower energy prices? Not according to Alistair Buchanan , chief executive of Ofgem, the energy regulator: “It is true that the US has transformed its energy market thanks to shale, but in our time-frame, when Britain will rely on gas for its power stations, this is not going to happen on any significant scale, either here or elsewhere in Europe.

Even if the US allows exports (and assuming they come to Europe), it will still cost about the same as we are paying for our winter gas now. No one doubts that there is plenty of gas out there, but what is critical to Britain is how much will be available over the next five years and how much we will have to pay for it to ensure that it comes here.”

Does public support count? The Prime Minister argued over the summer that “If neighbourhoods can see the benefits – and get reassurance about the environment – then I don’t see why fracking shouldn’t get real public support.” But what if it doesn’t? The NoFIBs petition (No Facking In Balcombe Society) was supported by 82% of local residents. It, too, is based on the precautionary principle:

The work of Cuadrilla poses an unacceptable level of risk to our water supply, air purity and overall environment. We, the undersigned, stand opposed to exploratory drilling or fracking for gas or oil because we believe that these activities put human health at risk, both of those living close to wells, but also of those whose water comes from an affected area.

The TUC motion originated from protests supported by trade unions and community organisations in the North West, where Cuadrilla first made the earth tremor. It adds: “The fracking method of gas extraction should be condemned unless proven harmless for people and the environment. This type of energy production is not sustainable as it relies on a limited resource. Until now, there is evidence that it causes earthquakes and water pollution and further investigation should be carried out before any expansion.”

In a field outside Balcombe village…

What of the environment? At Balcombe on a day visit, I had a long conversation with a local resident about the diverse environmental impacts of Cuadrilla’s drilling operation – see photo. The continuous noise, vibration and 24-hour lighting had driven birdlife, bats and badgers away. She feared the long term effects of injecting millions of gallons of chemical laden water to frack the gas on water pollution – the water table lies at 700 feet below ground level, the shale gas at 3000 feet down, so the drill pierces the water table. A few days later we also spoke about methane gas escapes and flaring.

She said, “We’ve been ignored. The petition, our planning objections, letters to MPs, our demonstrations haven’t stopped them. 10,000 people might.”

Who fills the gap politics has vacated? Speaking at the a recent Friends of the Earth meeting, John Ashton, for ten years the government’s roving climate change ambassador, argued that the struggle on climate change “is now entering a decisive phase.” The words Must, Now, Can should guide our thinking: “We must do whatever it takes. Otherwise the consequences of climate change will undermine security and prosperity. We must build a carbon neutral energy system, within a generation.”

But, he said, “The fact is, we can’t fix the climate problem, or any of the other problems on the agenda you have set, unless we can now fix politics itself. ” His prescription is to “Fill the gap that politics has vacated. Connect with the base of society. Mobilise coalitions to offer people solutions to problems that politics in its current form ignores. And do that on the basis of a more strategic assessment than I suspect you have of what is to be done and where you can change the game.”

And, as I was speaking with a local resident last week, a child ran by: “I love waking up in the morning here!” she said.

The challenge now for those opposed to Fracking across the UK

Carbon Brief’s new poll shows how little support there is for shale gas fracking in the UK. But while the poll suggests supporters of shale have problems to overcome, it also shows that anti-fracking have a real challenge ahead.

Shale gas wells have the lowest support out of any domestic source of energy. Fewer than one in five would support the building of a shale well within 10 miles of their home: that compares with more than half who support wind turbines.

But opposition to shale isn’t yet solid. There are still 40% who aren’t sure either way about local fracking, and fewer opponents than there are for both coal and nuclear. The argument can still swing either way.

And dig into the reasons for people’s opinions about shale, and it’s clear that both sides have problems.

Support for fracking is on shaky ground

The reasons why people support shale are strongly angled towards its being a crucial source of energy for the country.

This is a winning argument if the debate happens on a national level. Everyone knows we need some kind of energy source, so if people agree that shale can provide secure, low-cost domestic energy for the country, it’s hard to find a national-level argument that beats it*.

But this only works if fracking will happen in, say, desolate and sparsely populated places. It’s less effective if fracking happens where people live and you’re facing emotional** arguments.

The reasons for opposition to shale indeed show the challenge for its supporters.

Earthquakes and contaminated drinking water not only sound horrible for people living near wells – they’re also outrageous enough to mobilise outrage across the country. If the country believes that fracking causes so much local damage (regardless of whether it does), the benefits of energy security aren’t enough to win the argument.

Anti-frackers have to make a tough decision

But this is also a major problem for anti-frackers – who have a big decision to make.

There are broadly two ways of framing an anti-shale campaign. It can either be national and calculating, focused on greenhouse gas emissions and the lack of affordably extractable gas; or it can be local and emotional, focused on earthquakes and contaminated water supplies.

The national argument is losing right now. About twice as many say they support fracking because it reduces our dependence on imports, than say they oppose shale gas because it increases carbon emissions (perhaps it should have included methane, but I doubt that would have swung much). Even fewer are worried about whether there’s enough to extract or the cost of doing so.

So campaigners may choose instead to make their arguments local and emotional. This would be natural given current opinion and the potential potency of the arguments (ironically it’s the same approach that opponents of wind farms have taken)

But if you’re really opposing shale because of climate change or because you think it’s inefficient, relying on a different argument is risky. A few successful and safe shale extractions in the UK could undermine your campaign. In fact, media coverage over the last week or so has already begun to dismiss risks of earthquakes and contaminated water. If a campaign is based on earthquakes etc, and those don’t come to pass, it’s going to be in trouble after a year or two (though it’s true plenty of anti-wind farm campaigns haven’t been derailed by contradictory evidence).

Of course campaigns can try doing both: start with earthquakes and, if they don’t come to pass, fall back on climate change. But given how much less traction the climate argument has at the moment, it would need a lot of work to become credible. And switching arguments like that is always risky: you look opportunistic and unprincipled. Doing the two at the same time could mean doing both badly.

For now fracking is facing a tough time. Local protests make every new extraction controversial and politically difficult, and the fracking industry is struggling on the arguments it has to win. But the country is still largely undecided, and despite the current lack of support, evidence of successful extraction could undermine what is currently the key argument against it. Opponents may be doing well at the moment but the source of that support may not be stable.

Andrew Neil pretends he has ‘no view’ on climate change denial

In an expertly constructed apologia, Daily and Sunday Politics frontman Andrew Neil has sought to justify his approach to climate change and rebut criticism, following his recent interview of Ed Davey.

But a little examination of the piece shows not only that it can be easily picked apart, but also that Neil makes one fatally wrong assumption about the whole business.

There is, at the outset, a deliberate attempt to establish impartiality and propriety: “the Sunday Politics does not have a position on any of the subjects on which it interrogates people … it is the job of the interviewer to assemble evidence from authoritative sources which best challenge the position of the interviewee”. If only Neil had left it there, but he does not.

Readers are then told that one critic who has forensically dismantled Neil’s approach, Dana Nuccitelli, “works for a multi-billion dollar US environmental business”, and later that he is one of those taking “strongly partisan positions”. Thus he is, by inference, less trustworthy. Neil tries to link Nuccitelli to “deniers” (note use of quotation marks) but his critique does not contain one instance of the word.

Having marginalised his critics, and used his characterisations to justify dismissing the assertion that “97% of climate scientists are part of the global warming consensus”, Neil then makes a serious mistake. He talks of the science being “settled” (note the further use of quotation marks). But the science is never settled: this is a favourite attack line of climate sceptics.

Neil then moves to insert his own chosen sources in place of those he has dismissed as “strongly partisan” and allegedly in the pocket of business. And what a gallery he presents: Richard Tol, who has asserted that “The impact of climate change is relatively small”, and cited by US Senate Republicans wanting to debunk the scientific consensus, is prominent among them.

Neil also cites Hans von Storch, who believes that climate change has been “oversold”, and talks of “alarmists”, and Roy Spencer, a signatory to the Evangelical Declaration on Global Warming.

There is a world of difference between journalism such as Neil’s apologia – expertly crafted though it is, with its lofty pretence of disinterest and detachment – and the quality of scientific research that makes it into the 97% that constitutes the consensus on climate change. Neil’s fatal mistake is continuing with the pretence that there is some kind of equivalence between the two.

“The Sunday Politics has no views on such matters” he asserts. But he does.

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE