Recent Environment Articles

The government is trying to scrap the England Coast Path, and we need your help

by David Hodd

Does a coast path matter? As a nation we love the coast: whether we are talking of the Thames marshes depicted by Dickens and Constable, the rocky headlands of the South West, the White Cliffs of Dover or the formerly black beaches of Seaham’s coast.

Our relation with it is ingrained in our culture. No one is more than a 2 hour drive from it. This importance was recognised by the National Trust, with its Neptune Campaign – which was begun to protect the coast through acquisition, and to safeguard access along it.

Cornish business leaders are well aware of the £307 Million contribution the South West Coast Path provides the region’s economy each year.

But the English Coast Path is a £239k project to extend it around the English coast, and this means opening up access on land where some landowners have an instinctive dislike of the great unwashed.

Whilst Environment Minister Richard Benyon has been steadily sapping funding for the project, the Welsh Assembly have got their national coast path up and running, and as Visit Wales shows, it is the cornerstone of their tourism campaign.

I don’t expect an environmental, cultural or wellbeing argument to cut any ice with the famously buzzard hating Under Secretary. But right now, we need policies that get more of us spending more money, and circulating it in the economy.

A coastal path does this, and unlike quantitative easing, puts the money where it is needed and used. The coast path will benefit places like Hastings, Scarborough, or Workington. The Welsh path, in its first year, is thought to have generated £16M to the economy.

“Not interested in the environment, show me how you benefit business” ministers regularly holler at Natural England. But when presented with the economic benefit (on National Parks for example), it seems they are not listening.

Their prejudice filters out all reason. As with their attempts to sell off the Forestry Commission, we now need to show them what we think of their economically illiterate policies.

Sign up to the Ramblers petition now. Not sure a coastal path is your priority? Go for a walk this weekend on the coast nearest you – preferably a bit that Benyon’s landowning mates want you not to see, and then reconsider the maths, and think how much you value the view.

—

David Hodd’s website is: www.davidhodd.co.uk/

How the debate on climate change went wrong, and how we can turn it around

The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change will be out from September this year. This should be a big deal: it’s six years since the last report, and that was headline news at the time. The report will be a chance for climate change, and what we do about it, to be one of the top issues in public debate for the first time since the 2009 Copenhagen Conference.

But for climate campaigners, activists and anyone who wants better action on climate change, what should be done with this opportunity? I believe it would be a mistake to use the coverage of the report to try to score points in the same arguments that have dominated over the last few years.

Instead, there are other approaches that could reach a wider audience, move the debate past recurring arguments, and perhaps create a basis for more useful action on climate change.

We need to stop talking about climate denial

The problem, as I see it, is that much of the debate about climate change is dominated by whether or not it’s happening, how quickly it will happen, and the meta-debate about why ‘so many people’ don’t agree with the vast majority of climate scientists.

One reason this is a problem was explained by US Republican pollster Frank Luntz: he recognised the goal for opponents of government action on climate change should be “to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate”. So long as the debate is about the science of climate change – most people only hear that there is a debate, not what each side is saying – people aren’t talking about what to do about it.

But you might respond: how can we ask people to agree to action on climate change when they don’t believe it’s happening or caused by humans? It’s a logical question. But the polling shows that it’s a mistake to assume there’s a logical chain of reasoning. In fact, the debate about belief in climate change is based on two misconceptions: that people are widely and increasingly sceptical about climate change, and that their desire for action to tackle climate change depends on the extent to which they think it’s happening.

Because of these misconceptions, I think that the debate about whether or not climate change is happening is a distraction for people who care about climate change, and that we should change the subject.

The evidence is pretty clear that agreement with climate science is high and stable and that doubts about it are not increasing. The following chart is typical in showing that the same proportion now believes that climate change is real and manmade as did so before the UEA email hack. Most people think it’s real and manmade and a third think it’s real but natural; barely one person in 20 thinks it’s a fraud.

Agreement with climate science also fell before the start of the chart above, after a peak sometime around 2006 and the Stern Report.

But the polls suggest that what people say about their belief in climate change doesn’t have much to do with whether they want action to tackle it.

It’s such an important point I’m going to show two separate charts to demonstrate it.

Firstly, a poll just after Copenhagen showed that most people who said they think climate change is natural, or not happening at all, were satisfied with a plan to reduce worldwide emissions. To put it another way, over three in five ‘climate sceptics’ want international action to tackle climate change:

Just in case that was a freak or a mistake, we tested it again in the recent Carbon Brief poll. The conclusion was similar: of those who say climate change is natural and not caused by humans, nearly half want government action to tackle it.

So the evidence is clear. Outright climate denial is low and not increasing. Most people think climate change is real and manmade. And of those who think it’s natural or not happening, many still want government action to tackle it: a logical disconnect that suggests the debate about belief in climate change has been taken more seriously than it deserves. As Chris Rose has pointed out, responses to questions about belief in climate change are often about something else – a declaration of which ‘side’ the respondent is on. It’s not a debate that climate campaigners can win in its own terms.

The question is, if not scientists’ confidence about anthropogenic climate change, what should campaigners and communicators talk about?

Stick them with the pointy end

There are two key arguments that I believe are crucial for improving the case for better action on climate change – but which I don’t see being made at the moment. The first is that climate change is very likely to hurt people in the UK: people alive now and their children. Not just through indirect effects like more expensive food and foreign political instability, but also directly, through flooding and killer heatwaves.

There are people who’ll suffer more from climate change than Brits: people living on flood plains in Bangladesh, in low-lying islands, and in the Sahel, for example. And many wonderful species will become extinct when their habitat changes. Almost everyone is sad to hear about that and agrees that someone should do something. A few internationalists and conservationists might even do something themselves.

But nothing mobilises people like something that directly affects them and their family.

The pointy end of climate change – that the UK is very likely to face more floods and more killer heatwaves – is still largely absent from the debate. It shouldn’t be. The 2003 heatwave killed 2,000 people in the UK; it is likely that summers like that will be the norm by the end of this century. But only 34% in the Carbon Brief poll recognised that climate change is likely to cause more UK summer heatwaves.

This should include a ban among climate campaigners on references to global degrees of warming in conversations with anyone except climate change experts. The thought of the UK becoming 3° warmer sounds quite nice to me. You have to be familiar with the subject to understand what 3° means in practice: much wider variations in temperature and rainfall, with flooding and some summer days that are unbearably hot (yes, in the UK).

Essentially, what I suggest is that climate campaigners follow the example of this road safety film. Don’t just make the message about our responsibility to others, make it about what will happen to us if we don’t put it right:

We’re all in this together

The other argument that’s still missing is the one tackling the view that we shouldn’t make sacrifices for climate change because it would disadvantage us against other countries that aren’t doing the same, particularly China. It usually follows the structure: “why should we do X when China will just build Y power stations in the next week/month/year?”.

But the argument is much easier to rebut. It’s not true that rapidly growing countries like China are leaving the hard work on climate change to developed countries. China may be the world’s biggest emitter (though per person its emissions are still lower than the EU’s when including international transport and/or emissions from production of exported goods), but even as it industrialises it’s now using trading schemes to make it more expensive for its businesses to emit greenhouse gases.

So it shouldn’t be hard to knock back the argument that taking action on climate change puts us at a global disadvantage – and that’s before we start talking about the potential economic benefits of investing in low-carbon industries.

Change the subject

The debate about climate change has stagnated over the last three and a half years, stuck on belief in climate science. But that debate is based both on a dubious claim that scepticism is increasing and on the understandable but misplaced assumption that there’s a logical connection between belief in climate change and desire for action to tackle it.

The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report will be an opportunity for people who want action on climate change to get it back into the news and to start talking about something that feels meaningful for most people*. Partly this means neutralising the out-of-date criticism that it’s pointless for the UK to make sacrifices to reduce climate change when other countries aren’t doing the same.

But more important is to make the case that tackling climate change is a matter of self-interest for British people. This means recognising that most people are, naturally, more interested in what happens to themselves and their family than what happens to far-off people. The projected impacts of climate change for the UK – floods and killer heatwaves – are themselves serious enough to justify action: it’s time to start talking about them.

Major poll shows belief in Climate Change isn’t falling and scientists ARE trusted

Last week the site Carbon Brief released information on their extensive energy and climate change polling, which you can read about on their site.

But as with any apparently new information, it’s useful to put the results in the context of what we’ve seen before. How does the poll fit with what others have shown?

I’m going to pick on three places where it’s interesting to compare the new poll with previous ones.

1. Doubts about climate change aren’t rising

I’ve been banging on about this for a while. Poll after poll is showing that belief that climate change is real and man-made is at the same level it was at before Copenhagen, ‘climategate’, the UK’s cold winters, and the subsequent dip in belief.

The Carbon Brief poll adds yet more weight to this. Compared with a question asked by ICM in ’09 and last year, the results show no movement:

It really is time we stopped saying that belief in climate change is falling.

2. ‘Belief’ in climate doesn’t mean that much anyway

One of my favourite charts is from a post-Copenhagen poll that showed that, even among those who said they don’t think global warming has been proven, a majority wanted a reduction in worldwide emissions.

I’ve taken this to indicate there’s a bunch of people who respond to questions about whether they ‘believe’ in climate change as if they’re being asked “are you a tree-hugging leftie who hates business?” – so they say no to that question, but still want the government to do something about climate change.

But is that true? A question in the Carbon Brief poll supports that view, albeit not quite to the extent seen in the Copenhagen poll.

Of those who think climate change or global warming is mostly caused by natural processes (about a third of the total), 45% think that tackling climate change should still be part of the government’s economic programme:

3. There isn’t a big problem with trust in climate scientists

A poll conducted in March ’11 and reported 18 months later by LWEC found that only 38% agreed they trusted climate scientists to tell the truth about climate change. This prompted soul-searching among those worried about public perceptions of climate change.

The phrasing of the LWEC question – “we can trust climate scientists to tell us the truth” – is a very high bar. At a time when trust is low, expecting people to say they trust anyone to tell them the truth, without more reassurance, is asking a lot. I’m also not a fan of the way the trust question came after questions about exaggeration of climate change and agreement among scientists.

Add to this Mori’s trust index, which finds scientists are among the most trusted groups, and that trust in them has gone up over the last decade.

So I don’t think we should be particularly surprised that the new poll showed scientists are the most trusted to deliver information about climate change by a massive margin. The mistake was ever to doubt that they were.

Data from the polls will be published this week.

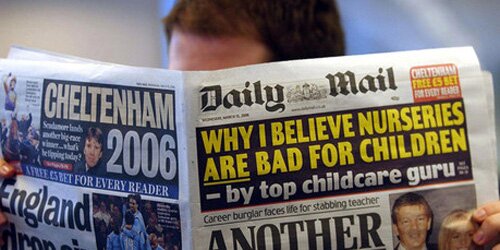

The Mail on Sunday’s David Rose keeps writing rubbish about climate change

It seems no Sunday is now complete without another pile of nonsense about climate change from David Rose in the Mail on Sunday (see my previous post here for example) and last week was no exception.

Rose has found a graph which he claims contains

…irrefutable evidence that official predictions of global climate warming have been catastrophically flawed. The graph on this page blows apart the ‘scientific basis’ for Britain reshaping its entire economy and spending billions in taxes and subsidies in order to cut emissions of greenhouse gases.

Typically for Rose the whole piece is riddled with inaccuracies and distortions – for example he completely misrepresents the views of climate scientist James Annan and repeats the easily debunked myth that scientists in the 1970s were just as concerned about global cooling as global warming.

But the main problem with Rose’s argument is more fundamental. The graph that he shows in order to support his argument simply doesn’t show what he claims it does. His “smoking gun” is not only not smoking, it is not even warm. Here is the graph in question

The graph itself is genuine – it has been taken from the blog of climate scientist Ed Hawkins and shows projections of surface temperatures from climate models going back to the early 1950s and forwards to the mid 21st century with different certainty levels, and actual observations to date. Rose is wrong about the certainty levels they actually represent 50% and 90% but I’m betting that this is an innocent mistake because (as we will see) he just doesn’t understand statistical terminology very well.

In this case all that is required to understand that the graph does not support Rose’s claims is the simple technique of just looking at it. The observed temperatures clearly follow the projections, spending much of the time in he narrower red band and during the whole 60 year period up to the present have fallen outside the 90% (or 95% as claimed by Rose) range just once, in the late 70s and then they quickly recovered.

Yes, we have had some relatively cool years recently (although 2010 was the warmest on record) and temperatures are currently touching the lower end of the 90% range, but then we have had a period of relatively low solar activity combined with repeated La Niña events, which have the effect of lowering global temperatures.

This kind of natural variability means that over shorter periods observed temperatures can plateau or even fall while CO2 levels continue to rise so it is dangerous to draw conclusions from such short periods – this is nicely illustated here. But even so global temperatures still haven’t fallen outside the 90% range. Does this really look like a “spectacular miscalculation” that “blows apart” the scientific consensus?

Rose cites Met Office decadal projections of global temperatures which, he claims show that “the pause in warming will last until at least 2017. A glance at the graph will confirm that the world will be cooler than even the coolest scenario predicted.”

So really Rose’s argument depends on what will happen in the future and he seems to place great faith in the Met Office’s forcasts, which is rather ironic since these are based on models and the whole point of Rose’s piece is to rubbish forecasts based on models. And in any case the forecasts show temperatures increasing over the next few years (it’s the dark blue line).

Rose further justifies his claims with this statement.

The graph confirms there has been no statistically significant increase in the world’s average temperature since January 1997

This statement is just bizarre as it is simply impossible to make that judgement based on the graph. There is no trend line (from 1997 or any other point) shown and even if there were it would be impossible to determine just by looking at it if it were statistically significant (ie it represents a genuine trend rather than just random variations in the data). One can only assume that Rose doesn’t actually understand the real meaning of this statement.

It is true to say that some scientists are now concluding that the higher end of the range of estimates for 21st century warming and climate sensitivity are looking unlikely. But then there was large uncertainty in such estimates anyway and the “most likely” ranges have not greatly changed and still give cause for concern.

We may or may not be heading for a climate change catastrophe but one certain thing is that the Mail’s coverage of the subject is truly catastrophic.

Myles Allen, another scientist quoted by Rose in his abovementioned piece, also claims his views were misrepresented.

—

cross-posted from Andrew Adam’s blog

The climate change denial industry’s dirty money-trail gets exposed

James ‘saviour of Western civilisation’ Delingpole eagerly recycled an article from a senior advisor to the Heartland Institute back in November 2011, because it gave him the answer he wanted to hear. The subject was “Green charities”, and the article rubbishing them had appeared in the American Thinker.

Had Del Boy plucked these organisations out of thin air? Well, no he hadn’t. Heartland has recently moved on from pretending that passive smoking can’t harm people to becoming a pillar of the climate change denial movement. The American Thinker is described as a “Conservative online magazine”. The two had been cited by Del because they are as reliable to his mind as Fox News Channel.

So what was Delingpole’s verdict on “Green charities”? These were held to be “way more evil and dangerous than Exxon or the Koch Brothers”. But the climate change denial lobby does plenty of its own charity fundraising.

That has been thrown into sharp focus by the Guardian, with an article about donor trusts and the sharply increasing amount of money estimated to be passing through them en route to funding climate change denial groups.

Under US law, donations made this way can be kept secret, but it appears that one recipient is the so-called Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow (CFACT).

CFACT, in turn, runs a website called Climate Depot, a repository of robustly expressed climate change denial, and here – for instance – there was a point-by-point rebuttal yesterday of anything climate related in Barack Obama’s latest State Of The Union address. This was enthusiastically trailed by Delingpole, who with customary subtlety called it a “fisking” of the President’s “eco-bollocks”.

Thus the climate change denial circle jerk in microcosm. The donor trusts also have the advantage that people like the Koch Brothers can slip the conservative and libertarian fringe a few million greenbacks this way too, and thus make it look as if they’re not really involved any more (the estimated amount of direct Koch donation more than halved between 2006 and 2010).

And this parallels the kind of non-transparent funding structure of UK organisations like the so-called Global Warming Policy Foundation, the premier British repository of climate change denialism.

This is something to think about the next time you see a conservative or libertarian lobby organisation popping up in the media claiming to be “non partisan”. He who pays the piper, and all that.

Why the Telegraph is wrong on the cost of wind turbines to our bills

by Damian Kahya

How much are we paying for the power lines that connect Offshore wind turbines to the UK?

A release from the reputable Public Accounts Committee reported in almost every newspaper claimed it was £17bn. That, the Telegraph calculated yesterday, adds up to £35 a year on household bills, and helping to pay for a 10-11% return on investment for those lucky enough to own a offshore wind power line.

But is it true?

1) It’s not £35 – it’s about £9.80 per household

It’s not hard to work out how the Telegraph got to it’s £35 figure. Take £17bn, divide it by the number of years it’s spread over (20) and then divide again by the total number of UK households (around 25 million) and – hey presto. It’s also wrong.

The cost of offshore transmission is added to bills – but (and this is a frequent mistake) it’s not just hard pressed households who use power.

Domestic consumers account for around 30% of domestic electricity demand. That means the Telegraph is off by about two thirds. So by our calculation the actual cost – per household – is about £9.80, or less than a pound a month.

But even that figure is not entirely accurate, for reasons we discuss below.

2) It’s not £17bn – its £566m so far, and its unlikely to add up to £17bn

The £17bn figure wasn’t calculated by the PAC committee, it came from a report by the National Audit office and applied to the total cost of building transmission infrastructure for offshore wind between now and 2020.

But that report was based on just four tenders - with a total value of £566m. There are two reasons why those may not lead to an accurate assessment of the future cost.

Firstly, as the NAO pointed out, the early competitions were ‘challenging’, not least because of the credit crunch. Much has changed since then, and following the NAO report the market regulator, Ofgem, started a review to see if consumers could get better value.

That review is expected to look in particular at one of issues which most vexed the Public Accounts Committee – whether the contracts should be fully linked to inflation. That means the total figure could wind up being significantly lower than £17bn.

“[Our] objective is to ensure this necessary investment is delivered at a fair price. As with any new market, there are lessons from early transactions. The initial tenders were conducted under interim arrangements,” said an Ofgem spokesperson.Ofgem claimed that so far the competition for licenses had saved consumers £290m.

3) 10-11% return is accurate – but limited

That means that the 10-11% return on equity investment the Public Accounts Committee highlights may not remain so high. That return also only applies to a relatively small portion of the £17bn spent. Equity – which is basically money from shareholders – is a relatively small share of big infrastructure investments.

Most of the money comes from lenders – such as the European Investment Bank or, the government hopes, our pension funds. Their returns will still be significant, perhaps around 6%, but not 10%.

All of which isn’t to say that the situation in peachy when it comes to offshore wind infrastructure.

The Public Accounts Committee’s recommendations include a number of suggestions which – they believe – could provide better value for consumers.

The complex system, by which the ownership of the transmission infrastructure was separated from the ownership of the turbines was designed to attract ‘institutional’ investors such as pension funds, generally too risk averse to buy wind farm.

But that has come in for criticism by some who say dividing up the system simply adds to costs. The committee’s main concern appears to be to avoid the risk of a ‘one way bet’ with consumer bearing all the risk of offshore wind investment, whilst investors get all the gain – as happened with government so-called PFI schemes to fund new schools and hospitals.

The problem is the story is far more nuanced and, frankly, hypothetical, than it has been portrayed so far.

ADDENDUM:

It’s been argued that the domestic consumer pays a larger share of the cost of renewables than industry and businesses, for example because of industrial exemptions to certain clean energy costs. It’s not clear if that would apply here – because these schemes are not funded through ROCs – but if it does the cost to households may be larger – though still nowhere close to £35.

—-

Damian Kahya is the Energydesk editor and former foreign, business and energy reporter for the BBC. You can following him on Twitter @damiankahya

Note to British media: climate change denial is NOT increasing

I’ll begin with two questions:

What proportion of Americans say there is solid evidence that the earth is warming? Is it: a) one quarter; b) one third; c) a half; or d) two thirds?

What has happened to that figure over the last four years? Has it: a) fallen every year; b) stayed about the same; c) risen every year?

Judging by most conversations I have and the coverage of public views about climate change, most people would guess the answer is low and falling.

But here’s the answer, taken from the Pew Research Center’s annual polls: two thirds and rising.

But here’s the answer, taken from the Pew Research Center’s annual polls: two thirds and rising.

Agreement in the US that the earth is warming is now higher than it’s been at any time since 2008. The research was conducted before Hurricane Sandy, so is probably higher now. Only about half say it’s because of human activities – though that has also increased by a quarter over the last three years.

The debate about public views of climate change has changed in the US over the last few months. A number of polls in the autumn showed that the public is becoming more worried – and this was covered in the media.

But the UK lags behind. This week’s Observer included a powerful editorial, restating the evidence about current and future impacts of climate change. But it spoiled it with the line: “climate change denial is becoming entrenched in the UK, or … our media have become complacent about the issue, or both.”

Everyone I speak to about climate change seems to think this. But, as I showed last year, concern about climate change in the UK is certainly not falling, and is probably increasing.

I don’t know of a single poll that shows that the UK public are currently becoming more sceptical about climate change. The general pattern is instead that there was a one-off increase in doubts around late ’09 , which has been followed by a recovery over the years since then.

This set of YouGov polls is fairly typical:

There’s a debate to be had about whether the media is becoming more doubtful of climate science, though again I suspect the opposite has been true over the last couple of years.

The narrative of rising climate scepticism has become entrenched well past its useful life. It’s time for some climate denial denial.

—

A longer version of this blogpost is here.

The ten whoppers by Boris on shale Gas and fracking in the Telegraph

by Damian Kahya

Britain should get fracking, says the Mayor of London in a surprisingly detailed intervention into the UK’s energy policy in the Telegraph on Monday.

We give 10 of his claims the once over in the same good humour as he makes them – albeit with far, far too many numbers.

1) The cost of disposing of their [nuclear] spent fuel rods is put at about £100 billion – more than the value of all the electricity they have produced since the Fifties.

Unproven.

This refers to an article in the Sunday Times which adds up the cost of decommissioning with the cost of nuclear power stations and compares it to the cost of power generated from Nuclear power calculated in today’s prices.

The decommissioning cost is not discounted and the cost in today’s prices may not represent the actual cost. Furthermore Mr Johnson appears to have ignored the construction cost, discussed in the article.

2) A new building like the Shard needs four times as much juice as the entire town of Colchester

False – external source.

The zelo-street blog points to an Independent article in which The Shard’s architect argues the building uses less energy than a town of 8,000. Colchester, it points out, has a population of 104,000.

3) The total contribution of wind power is still only about 0.4 per cent of Britain’s needs.

Unclear.

It’s unclear what units Mr Johnson means here. Does he mean our electricity or energy – which includes, for example, the gas we burn for heating or oil we burn for transport.

In terms of our electricity needs, wind generated 16Twh of power in 2011 compared to total generation of 364.9Twh. That works out at 4.4%. Relatively modest by European standards. The government wants total renewable generation to triple from 9.4% in 2011 to 30% by 2030.

Perhaps the Mayor meant energy. In that case you want to divide wind generation in 2011 by primary demand in that year. By our calculations you get 0.6%, which is closer – but still not 0.4. It’s likely there is a calculation which yields that number for energy – we just don’t have it to hand.

4) We are prevented from putting in a new system of coal-fired power stations, since that would breach our commitments under Kyoto.

False – but we’re being pedantic.

Our commitments under Kyoto don’t specify what we can and can’t build, they relate to emissions. The government has decided to rule out coal new build as one of the ‘least cost’ ways of reducing emissions.

5) We are therefore increasingly and humiliatingly dependent on Vladimir Putin’s gas

False

Figures from UK Trade Info suggest we don’t import any gas at all from Russia.

We do import lots of gas from Qatar which – coincidentally – helped to build the energy guzzling (apparently) Shard.

6) ..Or on the atomic power of the French state.

True

We imported 4.7Twh of (almost certainly) atomic power from the French state. That’s 1.3% of our electricity needs. Some may find even this modest level of imports from France utterly humiliating.

7) There is loads of the stuff [shale gas], apparently – about 1.3 trillion barrels - we could power our toasters and dishwashers for the foreseeable future.

Unproven

Again with the units. Gas, being a gas, doesn’t really come in barrels. Oil comes in barrels. We presume Mr Johnson meant barrels of oil equivalent (BOE).

By our (rough and ready) calculations 1.3 trn BOE of gas works out at 7,293 trn cubic feet of gas, which is, as Boris might put it, oodles more than anyone, anywhere, has estimated for the UK.

8) The extraction process alone would generate tens of thousands of jobs in parts of the country that desperately needs them.

Unproven

Cuadrilla has forecast that it’s operations in the UK could generate 5,600 jobs with around 1,700 of them being in Lancashire over nine years – presumably a ‘part of the country that desperately needs them’.

Shale drilling is also expected to take place in the Mendips and East Sussex where Cuadrilla are prospecting.

Shale in the UK however would generate revenues for the Exchequer and could – if reserves are sufficient – help the UK’s balance of payments as Poyry point out irrespective of what impact it has on jobs or bills.

9) And above all, the burning of gas to generate electricity is much, much cleaner – and produces less CO2 – than burning coal

True - probably

Generating power from gas is about half as polluting as using coal.

However, fracking is slightly more complicated. The process involves repeatedly using high pressure water to break up rocks so the gas is released up the well. However the water used itself returns to the surface still containing large amounts of methane. If this is not captured, but released into the air, it is 21 times more polluting that Co2.

As a consequence of these so-called ‘fugitive emissions’ some studies – including this study of atmospheric data around fracking wells by the US National Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) - has found shale to be almost as bad for the climate as coal.

10) As for the anxieties about water poisoning or a murrain on the cattle, there have been 125,000 fracks in the US, and not a single complaint to the Environmental Protection Agency.

False

The US EPA has recieved complaints about shale, like this one. UK regulations would be likely to be tougher than those in the US however, potentially reducing worries about localised environmental impact – according to the Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering. Tougher regulation, however, may also drive up some costs.

—-

Damian Kahya is Greenpeace’s Energydesk editor, and a former foreign, business and energy reporter for the BBC. You can following him on Twitter @damiankahya.

a longer version of this post is here

Why is Labour ignoring the biggest issue of our generation?

Last week when the government was in complete conflict over the Energy Bill, Ed Miliband was applauded for calling on them to stick to de-carbonisation targets. But it was a low-key speech, made in Scotland, only covered by the usual suspects.

Soon after, Ed Balls visited a wind farm with John Sauven of Greenpeace. Once again very little was made of it and the press barely informed when green energy was on top of the news agenda.

This has become a pattern. Last month, the private sector ruined Osborne’s party conference speech with a Times splash that said – “Go green or we quit Britain, energy firms tells Osborne.” How did Ed Balls greet the ensuing media interest? With silence.

There’s no doubt Labour has trouble getting attention for much of the noise they make around the NHS Bill. But they’re not new to the art of picking a fight (usually with Jeremy Clarkson) to get a story going in the press.

Along with many of their allies in the sector, I get the distinct feeling that the Labour leadership is shying away from the battle over renewable energy, green jobs and the Energy Bill.

For over a year, we have been letting the Tories get away with murder. On a vital issue, the Conservatives have moved away from the general public in order to promote and anti-science, anti-clean energy and anti-growth Tea-party wing of the party.

Why isn’t Labour making more noise about this? Some shadow ministers have claimed the media doesn’t cover these stories, but even if green investment and energy has been clogging the front pages for months now, Miliband is at his best when he sets the agenda.

It may be that the industrial policy followed by Ed Balls is still stuck in the past and sees the environment as separate to the economy. If so, he should have attended the TUC’s conference on the green economy only last month.

The public is on-side despite the attempts by the right wing press – every poll shows Britons preferred the UK to push for renewables over fossil fuels. A YouGov poll by Sunday Times last month found that 64% of UK want more wind or solar; only 14% want more oil or gas.

Perhaps Ed Miliband is worried the environmental credentials he inherited from pushing the Climate Change Act make him look too soft. But there’s nothing soft about the impact of Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey and New York. There’s nothing soft about the economic figures the CBI are bandying about. There’s nothing light-hearted about accusing the Chancellor of letting ideology rip our economy apart.

Climate change isn’t a soft issue – it’s a sledge hammer. The Tories are crazy for letting the environment slip from their fingers, all to appease their ideologically extreme backbenchers.

Cameron must be grateful that Labour is asleep at the wheel in calling him on it.

Why we need major action at the Climate Change meet in Doha

by Philip Pearson

As the UN assembles in Qatar for its 18th annual climate change conference, a new UN report warns of a 14 billion tonne “emissions gap” in 2020 between “business as usual” and the emissions level needed to hold the increase of global temperatures below the 2°C target.

14 billions tonnes is more than China’s carbon emissions in 2010 (11 billion tonnes). This week, too, the UK government publishes its long-awaited Energy Bill, but without a “decarbonisation target” for 2030, despite the Energy Secretary’s best efforts.

And so this message from a member of the trade union delegation in Qatar perhaps hits the spot: “Qatar is really a climate nightmare – worse than imagined. Malls with ice skating, gondolas (Venice-style), and the slogan from the Qatari hosts: “Shop til you drop – spend your all-day leisure time shopping and socialising with multi-national shoppers in the malls.”

Last week, too, the World Meterological Organisation reported a new high of 390 parts of CO2 per million in 2011 – the green line, below:

Meanwhile, a new World Bank-commissioned report warns the world is on track to a “4°C world” marked by extreme heat-waves and life-threatening sea level rise. Adverse effects of global warming are “tilted against many of the world’s poorest regions” and likely to undermine development efforts and goals.

The largest increase in poverty because of climate change is likely to occur in Africa, with Bangladesh and Mexico also projected to see substantial.

In Qatar, the trade union delegation is calling for:

» A second commitment period for the Kyoto Protocol, which expires in December 2012.

» Real commitments from Governments to close the “2020 gigatonne gap, which must mean the US and Canada get on board.

» A new legally binding agreement applicable to all and to be finalised and in force by 2015.

» A commitment to Just Transition measures on green jobs, a place at the table for trade unions, and trade union rights of the kind largely denied by the Qatari Government.

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE