Recent Africa Articles

We badly screwed up in Libya, and it’s time to admit that

There are usually two kinds of people who like to commentate on foreign policy matters: those who oppose any military ‘intervention’ in the affairs of other countries; and those who have no problems advocating military intervention and will always defend such action.

I happen to be in a third, less media-friendly category of people who thinks military intervention in the affairs of other countries is a possible last resort providing:

– it is carefully judged and isn’t rushed into

– has a clear purpose and exit plan

– the public is adequately explained why such action is necessary and support it in significant numbers

– the plan isn’t to leave the country in a worse state than it was

I accept that this is too nuanced for many people, especially on Twitter… but ¯\_(?)_/¯

Anyway. I also believe it really helps foreign policy debates if politicians admitted when they fucked up. I’m actually still astounded that Tony Blair – and Nick Cohen, by the way – aren’t embarrassed to continue opining on foreign policy affairs and defending the invasion of Iraq. Living in a bubble makes you oblivious, clearly.

Like Iraq, we fucked up in Libya. We should say this so we can learn from it.

I mean, here we have Jonathan Powell, Tony Blair’s former chief of staff who was then appointed by Cameron as the UK envoy, saying: “Libya could, if it goes down this spiral, end up as a failed state.”

WTAF? There is no mention whatsoever of the UK’s hand in deposing Gaddafi (which I supported at the time), and yet doing nothing whatsoever to ensure a transition to democracy. We have screwed up and yet we’re pretending it’s the Libyan people’s fault their country has collapsed into violence. It beggars belief.

This has now become a pattern: we get involved in foreign conflicts and then we absolve ourselves of responsibility if the country collapses without proper institutions being put in place. Libya is in trouble because of us. We should have helped put institutions in place but we were too busy leaving to declare victory.

Aside from the lives lost in Libya, these kind of screw-ups also dampen public enthusiasm for genuinely necessary interventions in places like Syria*. Our own short-sightedness in foreign affairs is costing lives – of others and eventually ours, through blowback.

—-

* PS – I don’t accept Cameron passed the above tests when rushing into Syria over chemical weapons, which is I supported Miliband’s brakes on the process.

David Attenborough and other food facts about Africa you probably didn’t know

by Jonathan Kent

Many, but by no means all Greens are worried about population. It’s a multiplier on many of the problems we face. But it’s a very sensitive subject, as David Attenborough has discovered.

When I heard Attenborough say: “what are all these famines in Ethiopia, what are they about? They’re about too many people for too little piece of land. That’s what it’s about,” I hear the echoes of generations-old, lazy thinking about Africa and Africans summed up in the notion of the White Man’s Burden.

A little while ago there was a row about whether Green World, the magazine for Green Party members, should take an ad from the group Population Matters of which Attenborough is a prominent supporter. I argued, quite vociferously that it should; I dislike any attempt to stifle debate.

The anti-Population Matters lobby, among them Lib-Con regular Adam Ramsay, pointed out that the carbon footprint of a country like Mali is so small compared to Western nations that the population could double, treble or more without having much impact on the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

True, though unless we keep Malians poor or we can roll out clean energy fast that may not remain the case. And every African needs to eat the same minimum as every European, and even people in the rich West can only eat so much. Over-population results in countries hitting a food production buffer long before they hit an energy buffer.

But David Attenborough and others also need to stop blinding ourselves with stereotypes about Africa.

Firstly, in simple terms of density sub-Saharan Africa is far less populated than North West Europe, the Indian subcontinent, China and Japan.

Then, when one looks at which nations import and which export food, an even more interesting picture emerges. Many West and East African nations are net food exporters – Ethiopia included.

What do they export? Well next time you pick up a packet of mange-tout check out its origin. Chances are it’ll come from Kenya along with cut flowers and other products that drink up water and use valuable agricultural land.

Yes, populations outstripping the ability of the land to support them is a problem; but not in Africa. It’s a problem in Japan, and Saudi Arabia and Russia. It’s a problem in South East England and potentially across most of Europe too. But those are wealthy countries, so we don’t tell people there to stop having children.

Africa’s problem, on the other hand, is one of economics and justice; debt, balance of payments, the need for foreign currency and poverty. It’s about foreign governments and corporations (the Chinese prominent amongst them) buying up land because they know that rich nations consume more food than they can.

If only David Attenborough were as knowledgeable about the human as he is about the animal world he might have talked about the Black Man’s Burden – part of which involves feeding Europeans who are quick to advise, slow to listen and who, for the most part, simply don’t seem to care.

—

Jonathan Kent blogs here.

Mali is not Afghanistan, and other simplistic media narratives

by Riazat Butt

Military activity brings out the worst in people – and I’m not talking about militants.

In case you missed it Africa – yes all of it – is the new Afghanistan. How could it not be? It has crazy Muslims killing innocent Muslims and lopping off their bits.

The entire continent is antagonising Western governments, while simultaneously highlighting the shortcomings of local security and law enforcements, to such an extent that boots on the ground are inevitable. It sounds so familiar.

Any western intervention in foreign lands is almost immediately described as the new Afghanistan.

Exhibit A:

Will Libya become the new Afghanistan? asked ABC News in September 2012

Libya IS [my emphasis] the new Afghanistan, said the Telegraph in August 2011.

A few months before the Telegraph arrived at that conclusion the Defence Secretary Liam Fox said Libya WAS the New Afghanistan.

Exhibit B:

Last October Al Jazeera asked whether Syria was the new Afghanistan. There’s a pattern emerging.

There are a few reasons why Africa/Mali/Algeria is not the new Afghanistan (which, remember, is the new Vietnam) but that hasn’t stopped experts from drawing comparisons. And, because nobody knows WTF is going on, they get away with it.

North Africa is the new Afghanistan, says Front Page.

North Africa: the New Afghanistan? asks ABC. You see NA = North Africa. NA also = New Afghanistan.

Will Mali become a new Afghanistan? wonders Arab News. Arab News? C’mon guys! You’re Arab! You should know better. Oh wait.

USA Today has a different take on the situation: Is Africa Al-Qaeda’s new launch pad? Yes, that’s the whole of Africa. As opposed to the Africa that is home to groups that we’ve already heard of – AQIM and AQAP.

Salon doesn’t fall into the same trap though, oh no. It asks: Is Afghanistan worse than Vietnam?

Here are some very good reasons why Africa is not the new Afghanistan

The grand-sounding AQIM hides a chaotic reality. The group has singularly failed to unite disparate local groups spread along the north African coast. Even in Algeria, militants are split between the north and south – and these two factions are split again, into rival bands. Finally, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, the man suspected of orchestrating the refinery attack, leads his own breakaway group that does not even pay nominal allegiance to the southern AQIM faction, let alone the group as a whole, and certainly not to al-Qaida. If they are “al-Qaida-linked” then the chain is a very long one.

That’s from the Guardian’s Jason Burke, who knows more than a thing or two about all things Al Qaeda.

A few days later he said something similar, mostly because the likes of Cameron started talking about an existential, global threat and clearly some calm and perspective was needed.

Cameron did avoid talking of a “war” but, as his own intelligence services and foreign affairs specialists have long advised, the “single narrative” of a cosmic planetary “existential” clash is, for theological as well as psychological reasons, one of the best recruiting tools the militants have. Such rhetoric therefore risks being counterproductive. The new challenge this decade may be an unforeseen one: the hard-learned lessons of last decade being neglected, if not deliberately unlearned.

Professor Michael Clarke, now of RUSI formerly of King’s College London, warns that western responses to African events are not a continuation of the same jihadist challenge that produced the 9/11 attacks and much else thereafter.

Nevertheless, the difference between what is happening in the Sahel now and what happened in south Asia, are more evident than the similarities. For one thing, the jihadists are aligning themselves with separatist movements more than revolutionary ones. Al-Qa’ida was always based more on guerrilla warfare than international terrorism as such. It was what they trained for and how they saw themselves pursuing – ‘Qur’an-style’ – a proper jihad against the infidels.

And, just to hammer the point home, here’s Christina Hellmich on why the Islamist threat to Europe is overstated.

…when David Cameron announces that Britain must pursue the terrorists with an iron resolve, he unwittingly reinforces a notion of a unified Islamist threat that does not exist in that form. It is a convenient narrative which benefits both the propaganda machine of Islamists and the calls of those in the west who support military action, yet the true picture of those who claim to act in the name of al-Qaida – both in Africa and elsewhere – is far more nuanced, and much less of a threat to Europe, than we are commonly led to believe.

Here endeth the sermon.

—

Riazat Butt was religion correspondent at the Guardian. She now blogs here.

Iceland’s President: we were saved by avoiding austerity

This week at Davos, most of the time the world’s richest people spent time patting each other on their backs.

But there were some good parts too. Al-Jazeera briefly interviewed Iceland’s President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson on how the country managed to turn around its economy so quickly.

He says:

I think the primary reason is that we were wise enough to realise this was also a fundamental social and political crisis, but overall we didn’t follow the traditional prevailing orthodoxies of the western world of the last 30 years.

We introduced currency controls, we let the banks fail, we provided support for the poor, we didn’t introduce austerity measures of the scale you are seeing here in Europe… and the end result four years later is that Iceland is enjoying progress and recovery very differently from the other European countries that suffered from the financial crisis.

If there is a clear example of a country that bucked the austerity trend and rebounded quickly, Iceland is it.

(via Bright Green Scotland)

The British anti-war left and the sudden interest in Mali

Since Friday, when white people started fighting there, it seems anyone who’s anyone in the mainstream media is an expert on Mali. Funny that.

I’m no expert, but back in April 2012, I wrote:

Meanwhile in Africa, a nascent democracy has fallen, a large part of the country is in the hands of a different number of armed groups with differing levels of affiliation to Al Qaeida, trouble is spilling over into neighbouring countries and refugees are on the move. All this is happening as a direct result of the UK’s last major military intervention.

I speak, of course, of Mali, and the vast desert area referred to as Azawad by those Tourags who seek its independence. Over the weekend the major town Timbuktu and Gao have fallen to Touareg rebels, taking strategic advantage of the recent coup d’etat. This coup d’etat was itself undertaken by a section of the army supposedly as a reaction to the civilian government’s inability to deal with armed rebellion in the North, and that armed rebellion was fuelled by the massive overspill of weaponry from Libya via Niger into the desert regions of Mali.

In the mix are various groups, with confused and confusing allegiance, and including the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), the (Islamist) Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA) , the (Islamist) Ansar al-Din and of course Al Qaeida Middle East (AQIM), present in one form or another (from bases in Southern Algeria).

More details are here, courtesy of the very excellent Kal at The Moor Next Door. There’s a handy map here. I don’t pretend to out-analyse Kal on the specifics of what are and what will be in the region, but simply ask the questions: do Cameron and Hague now accept that what seemed like a nice Boys’ Own Adventure is turning out to have very nasty consequences not just for the millions now directly affected (Mali’s population is 16 million to Libya’s 6 million) but potentially for the much of the Sahel and into the West African states?

Nine months on, we know a few more details of those “nasty consequences”. There is open war in Mali. Ansaru in Nigeria are explicitly linking their activities to Mali. Senegal is scared of what may be coming. Mauritania, in its fragile state, is unable to restrict the movements of jihadists through its territories and prey to attack on its own towns, and Niger – already beset by major ecnonomic and environmental problems, will only suffer more from the growing regional instability.

Now if I, from a backroom in Lancashire, armed with nothing more than an internet connection and a keen sense of the unintended consequence, was able nine months ago to predict pretty well how things would pan out, then it must all have been pretty damn predictable. You’d have thought, in such circumstances, the anti-war left would have had something to say in the way of prevention.

Yet by and large, none of the people or organisations now so desperate to comment on what are, by any yardstick, serious, bloody events with huge consequences for the people of the Sahel region and beyond, had anything to say as, little by little over the summer months, the groups who had been fighting for territorial independence ceded ground and towns to those with more Jihadi aims, and it became clearer that the assault on human freedoms in Northern Malian desert towns would soon be in assaults in Central Mali.

In the end, I can’t help feeling that while what is happening now in Mali is actually quite welcome news for some on the left, who are happy to use it to reinforce their anti-imperial narrative or whatever, the energies and resources now devoted to commenting on the war, might have been better used more proactively few months ago.

Of course it’s a big ‘if’, but if leftie commentators, journos and politicos had been demanding answers from the government back in the summer about how it intended to deal with what was unfolding in Mali, then it might just have hit the Cabinet agenda, and it might just have kickstarted an international process of support for regional intervention. As it was, it was December by the time ECOWAS came to a tentative agreement on use of its regional forces to support the Malian government, and by that time it was too late; French military intelligence clearly saw both that the route South was open to the jihadists, and that the jihadists had the capability and desire to take that road, and that if it didn’t strike now Bamako itself would be under threat (of course it may still be, but in a different way).

Of course the anti-war left is not responsible for what’s going on now – Cameron and co must bear some responsibility for that given that we now know how well briefed they were, or at least should have been, on the likely consequences for its southern neighbours of a changed regime in Libya.

But if the anti-war left is going to get serious about anti-imperialism/promoting the long-term advisability of stopping these continued interventions – we can be sure enough there’ll be another one along in the non-too-distant future – it had better start by getting serious about its analysis.

The dilemma: how to get more girls in developing countries to go to school

It’s been 50 days since 15 year-old Malala Yousafzai was shot in the head by the Taliban for advocating for the rights of girls to go to school in Pakistan. The country has the second highest number of out-of-school children in the world, after Nigeria – and two thirds of them are girls.

In fact, girls are less likely to be enrolled in primary school compared to boys in virtually every country in the developing world. (pdf)

While the international community has been actively trying to address this problem via the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), it has failed to tackle one of the core reasons girls are out of school: violence.

Research by ActionAid and the Institute of Education in Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria and Tanzania found that up to 86% of girls had reported some form of violence against them in the previous 12 months. This violence in turn was found to directly affect whether girls attended or completed school.

Just a few days after the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, the Secretary of State for International Development, Justine Greening, announced a new pot of funds specifically focused on tracking what works in responding to violence against women and girls. The £25 million fund will operate over five years in ten countries in Africa and Asia and will have a priority emphasis on prevention – stopping violence in the first place.

This new investment is critical. Up to 70% of women face gender-based violence at some point in their lifetime. This violence affects women of all cultures and classes in all countries, and is one of the core reasons women are more likely to be living in poverty. It denies women choice and control over their lives and is one of the most widespread human rights violations in the world.

And yet change is possible. A five year ‘Stop Violence Against Girls in School’ project by Action Aid running in Ghana, Kenya and Mozambique for example has seen consistent – and in some cases dramatic – improvements in girls’ enrolment in school. From 2008 to 2011, the percentage of girls enrolled went up by 20% in Ghana, 60.7% in Kenya and 59.5% in Mozambique. Dropout rates have likewise improved across the life of the project.

In Afghanistan, ActionAid trained women paralegals to provide legal and psychological advice to other women. With this training, they successfully brought 480 cases of violence through the justice system; only eight cases had ever been previously reported. And in Zanzibar, ActionAid set up four shelters, providing survivors of violence a safe place to stay where they can access legal support services. Previously, there were none.

The key to this work being successful is ensuring there is adequate investment in the necessary ingredients for change. As this Theory of Change (pdf) explains, there are four ingredients:

1. Empowering women and girls

2. Changing the social norms that condone violence against women and girls

3. Building political will and legal and government capacity to prevent and respond to violence against women and girls

4. Providing comprehensive support services to survivors of violence – including appropriate medical help

It is past time to acknowledge how violence is undermining progress on all of our development and social justice ambitions and yet is not included at all in our targets for change.

We need now to hear the Government confirm that it will fight for a dedicated target on how to eliminate violence against women and girls in the framework that comes after the Millenium Development Goals too.

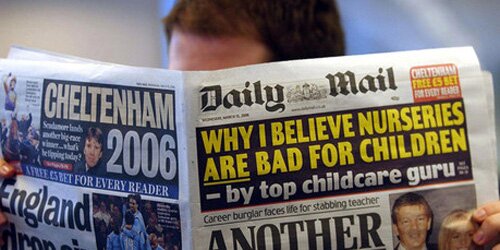

How the Daily Mail lied about aid to a Ghanian village

Journalist Ian Birrell recently went to Ghana to follow up on a story about an American aid organisation, and British funding for it.

The headline screams: “How your money is being squandered: The African village where EVERY family is getting £7,500 from the British taxpayer”

The story concerns this five year project in Northern Ghana, and a quick perusal of the Business Case shows that the nineteen word headline contains three lies.

continue reading… »

The #stopKony campaign was genius – but did it really backfire?

Twitter was awash with references to Joseph Kony yesterday – the leader of the murderous Lord’s Risistance Army (LRA) in Uganda. It was in fact trending at the top of Twitter for most of the day and many thousands discussed it on Facebook too.

What kicked it off? A very effective video. Now, I’m rather shocked over 20 million people watched a 30 min video online (I get bored after 4 min) but it worked.

Halfway through the day I started seeing lots of links pointing out that the charity behind the video and its content were not all they seemed. But did the campaign really backfire?

continue reading… »

Starvation in South Sudan: how to help

contribution by Tim Flatman

In May last year, up to 150,000 people were displaced from Abyei when the Sudanese Armed Forces invaded the area, burned down the local Ngok Dinka population’s homes and looted schools and churches for materials that can now be found for sale in Muglad market.

I have just returned from a visit to Abyei, where I was able to meet with the first returnees north of the river Kiir, and distribute a small amount of food ($1200 worth of grain & flour) bought with donations from family and friends.

Government soldiers are still present in the town, but the former residents of the area have started to return to their villages and report that they are well-protected by the Ethiopian peackeepers (UNISFA) who are now fully deployed in the area.

But they missed the last planting season while they were displaced and have no food available now. They are surviving on wild fruit and gum, but report that they are not sure if some of it is poisonous and that it is making them ill.

A lack of food is not deterring returnees from telling their family and friends to come back. They cite a number of reasons – the most important of which is their strong emotional attachment to the land where their ancestors have lived and died.

Numbers of returnees will continue to rise, despite the food shortages. Pressure must be brought to bear on NGOs to carry out regular distributions, as well as fixing water pumping systems that were vandalised by the Sudanese Armed Forces.

In the meantime, people are starving now, and so with the help of friends and family of the returnees in nearby Agok, I intend to carry out a distribution as soon as possible.

£4,000 will be enough to buy and transport enough grain to feed the returnees for a month.

For more details and to donate, go here: http://grassroots.org.uk/home/fundraising/abyeisudan

—

[A longer article will soon be posted at reliefweb and will be linked here. Video clips from Tim’s visit are starting to go up at http://www.youtube.com/user/FriendsofAbyei]

Is our intervention in Libya already back-firing in our faces?

I was never a supporter of the West’s military intervention in Libya. All I could think of were ulterior motives: oil, defence contracts, geo-political influence in such a vital and unstable part of the world.

Also, why help Libya but not other countries rising up against tyranny?

The Economist wrote that not intervening everywhere was no reason not to intervene somewhere. I accepted this as a plausible argument, but still found myself against intervention.

continue reading… »

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE