Recent Foreign affairs Articles

In France, austerity being used to undermine the state pensions system

by Tom Gill

A showdown between the French Government and unions is looming over reforms to the country’s ‘generous’ pension system.

Strikes and protests are scheduled for September 10 in response to plans by the Socialist administration of President Francois Hollande to extend the 41.5-year contribution payment period required for a full pension and other possible changes.

Hollande has indicated he has no intention of touching the retirement age that former President Nicolas Sarkozy raised to 62 from 60, having fulfilled a campaign pledge to roll it back for those who started work early. Nor is he minded to trim annual pension increases to below inflation, another option under consideration.

Employers berate the President for timidity, and say more cuts to the system are needed to plug an expected 20 billion euro funding gap in the system by 2020.

‘We cannot wait any longer and be content with half-measures because our pension system is in a disastrous state,’ the new head of France’s Medef employers organisation Pierre Gattaz wrote in an op-ed in Le Monde newspaper this week

Medef will be making this point at a meeting with the government and unions on Monday and Tuesday, when Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault is expected to formally outline the reform plans.

Gattaz said it was ‘urgent’ to review pension arrangements allowing the military, police and others to retire much younger, although Hollande is expected to leave them unchanged too.

The head of the Medef employers’ group also called for France’s state-dominated pension system to be curtailed and a bigger role given to privately funded pensions.

Public spending on pensions is 14.4 percent of output in France versus 12.9 percent in the EU.

Businesses in the eurozone’s second-largest economy, which has just exited recession, fret about a prospective rise in payroll taxes as part of the pension system reform. Gattaz claims that increasing their contributions would hurt employment further at a time when more people are out of a job in France than ever before.

And it is not just employers breathing down Hollande’s neck – the European Commission is reportedly looking for indications that the government is serious about ‘reform’ in exchange for agreeing some loosening of the country’s timetable in reigning in its deficit.

Hollande is right to fear a popular backlash against changes to the country’s pensions system. All past attempts – including under Sarkozy – have encountered weeks of demonstrations and costly industrial strikes.

But is ‘reform’ – in the modern turn-the-clock-back meaning of the word – inevitable?

First, it is important to clear up the nonsense that pensions are generous in France – the average pension is only 60 percent of working-age post-tax income, versus the 69 percent average for industrialised countries. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/07/21/uk-france-pensions-analysis-idUKBRE96K02W20130721

Second, companies will be able to claw back much of the rise in employer contributions (+ 0.1%, or 3 billion euros) expected in the changes, through tax breaks, and they will still be paying less than they did 20 odd years ago, point out Catherine Mills, from the University of Paris I Panthéon Sorbonne, and Frederick Rauch, editor of the journal Économie et Politique.

Third, the problem is not the cost of the system per se, but the lack of funds to underpin it. In an article in L’Humanite newspaper http://www.humanite.fr/social-eco/des-propositions-alternatives-pour-le-financement-547054 Mills and Rauch point out that this is due to rising unemployment and downward pressure on wages, the result of austerity policies pursued in France and Europe, and the fact that firms are more than ever putting shareholders before employees.

Firms now pay out twice as much to their owners and for their financing needs than on payroll taxes. Indeed, the proportion of companies’ financial resources handed out as dividends has risen from 30% to 80% since the end of the 1980s, according to a report in Alternatives Economiques. http://www.alternatives-economiques.fr/pourquoi-les-entreprises francaises_fr_art_1217_63975.html And a tidy 100 billion euros were pocketed by fat cat shareholders of France’s largest companies in the three years to 2011 alone.

The two economists calculate that a drop in the wages paid by employers of 1% costs the pension system 800 million euros in revenue. When the country has 100,000 more unemployed, the pension system loses 1 billion euros in funding. Thanks to economic rigor in France and across the Continent, the country now has over 10% out of work. ‘Thus boosting employment and wages is the key to making the pension system sustainable,’ say Mills and Rauch.

All of which implies an end to the mad, self-defeating austerity policies prevailing across Europe, and a radical ‘reform’ (in the traditional sense of the word) of the capitalist system.

—-

Tom Gill blogs at www.revolting-europe.com

How ‘data’ played a part in the re-election: Obama’s Director of Data explains what happened in 2012

by Ethan Roeder

The Conservatives have hired Obama’s campaign chief Jim Messina for the 2015 election. How valuable will he be? How did ‘data’ play a part in the 2012 US election? To answer the question here is the man himself: Ethan Roeder was Director of Data from Summer of 2011 till Election Day.

In a special piece for Liberal Conspiracy he shows the slides he used internally and offers an explanation for each below. He also wrote a piece for the NYT titled I’m Not Big Brother. This presentation offers some idea of what Jim Messina will be focusing on for 2015.

—

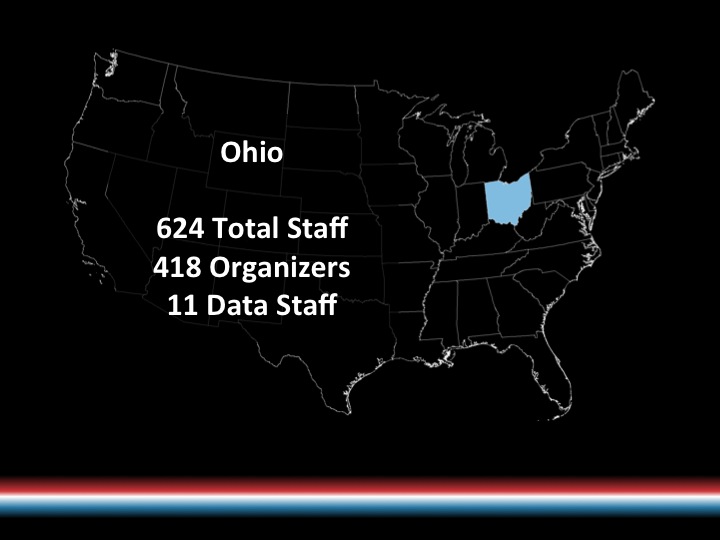

On Election Day, 2012, the Obama campaign had 107 dedicated, full-time data staffers in 19 states. To build an army of data staff, we realized, we would need to find new recruits and put them through boot camp. We designed a five-week online course that ultimately transformed a select group – drawn from over 2,000 applicants – into some of the most effective data staffers to ever work in politics.

Our campaign team was doing exactly what they were being paid to do- steering clear of a distraction that bore no relevance to the banner issues of the campaign. Yet this policy of deflection led to distractions of its own: open speculation. Before long we were supposedly encouraging our supporters to spy on their neighbors and monitoring the porn consumption of voters. By declining to offer a narrative of our own we created an opening for everyone with curiosity and a keyboard to sort out for themselves what must be going on in the infamous “cave.”

Of course the speculation wasn’t only negative. Some of the awed accounts of our game-changing accomplishments were just as detached from reality as the conspiracy theories. Obama didn’t win because of new technology and his campaign didn’t contact 40% of the American population. Obama won because he was the better candidate. Data, Analytics, and Technology served the President in his effort to connect with and motivate voters.

You can’t turn a turd into a victor using some brains in a back room. What follows is a crack at the reality of what Team Data did – and did not do – on the Obama re-election.

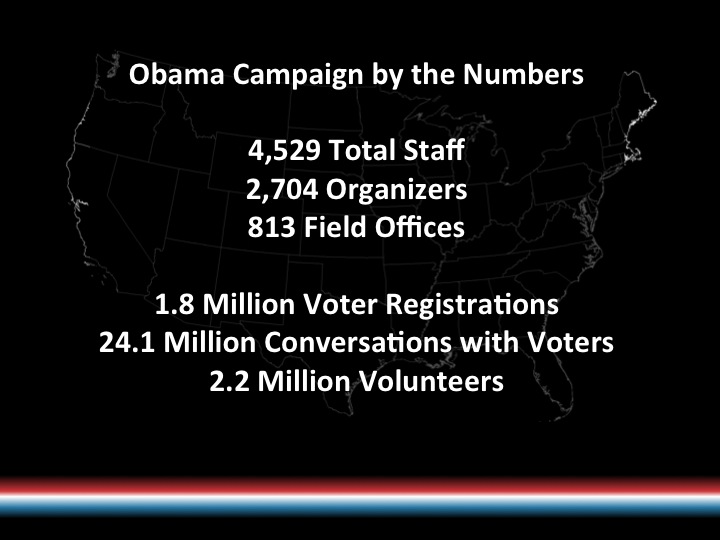

By Election Day, the Obama campaign had over 4,000 paid, full-time staff. Most of them were Field Organizers working out of over 800 offices in key battleground states.

By comparison, the Romney campaign had fewer than 500 field offices. The Obama approach to data cannot be separated from our commitment to investing in field.

Staffing in a typical state included a Data Director and a number of Deputy Data Directors.

In a large state such as Ohio, deputies may have been responsible for specific program components such as daily progress reports, early vote data, polling location data, data trainings, mapping or in-state tech development.

Data is a turbo booster for campaigns.

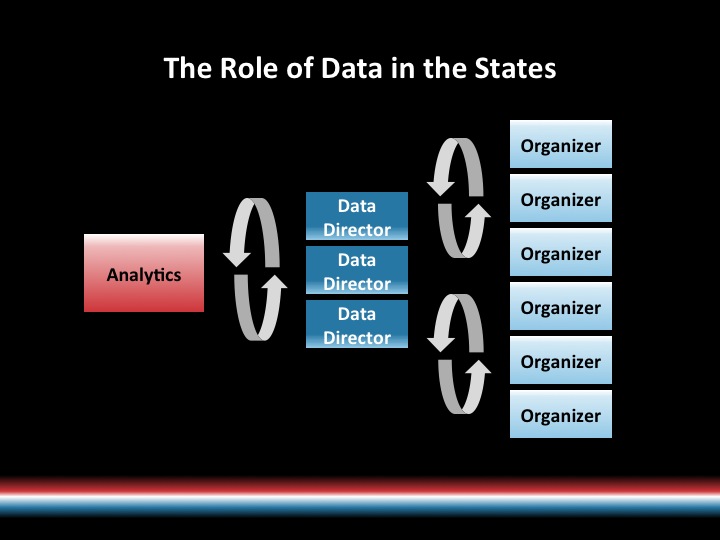

One way to think of the Data team is as the bridge between the strategic intelligence our Analytics team provides and implementation on the ground.

A data director works with other members of the state leadership team to determine program goals- the most obvious of these being how many votes are needed to win.

The next step is calculating capacity- how many volunteers have been recruited, how many more can be recruited in the lead up to the election, and how many voters can be contacted total?

Once that strategic groundwork has been laid the final step is using voter contact models to determine the final lists our field organizers will work from.

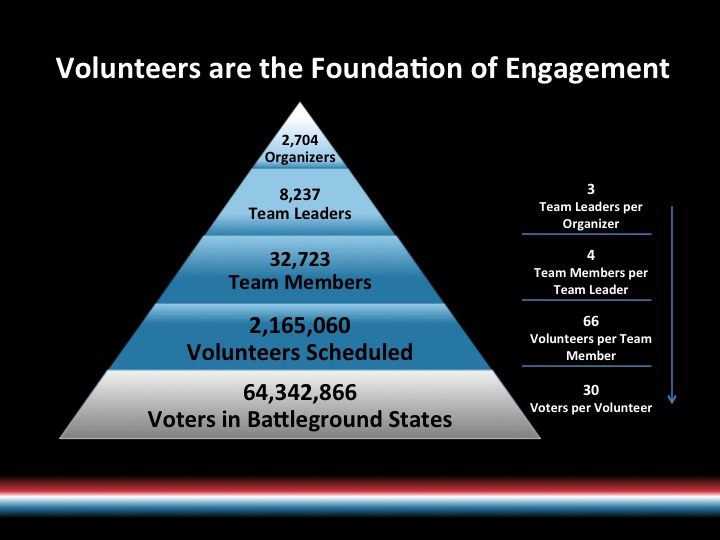

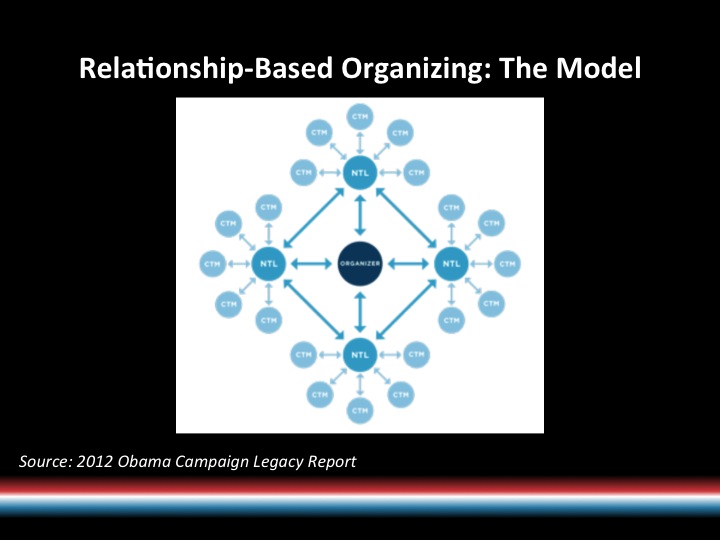

The campaign identified and trained over 8,000 volunteer “Neighborhood Team Leaders.”

These volunteers would assume responsibility for organizing their own neighborhoods and recruiting other volunteers to help deliver their area for Obama.

These NTLs worked with an assigned Field Organizer (a paid staffer) and were given target goals, progress reports, and volunteer prospect and voter lists to help them achieve their goals.

By training volunteers to take on leadership roles and by holding them accountable to firm goals we were able to expand the reach of our campaign.

This organizing model, also known as the “snowflake” model, can be used by any campaign large or small to turn the excitement about a campaign into productive action on the ground.

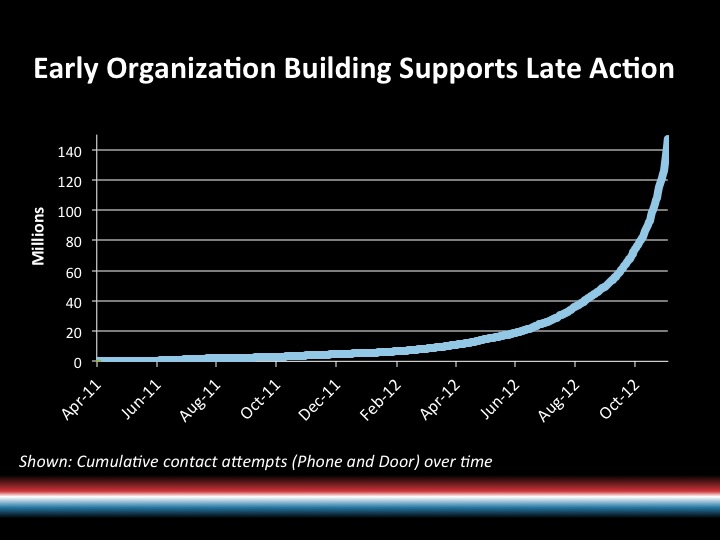

Campaigns interested in using relationship-based organizing to build strength on the ground must commit early resources to organization building. This presents some challenges for a campaign.

First, staff hours that might otherwise be directed towards more immediate and tangible activities (such as voter contact) must be reserved for the time-consuming activities required to recruit and build relationships with volunteer leaders, train them, and manage them.

Second, it can be difficult to build excitement and urgency when election day is in the distant future. When these challenges are met and overcome, however, the payoff is enormous. From the 2012 Obama Campaign Legacy Report: “On November 6, 2012, the last day of voting in the most important election of our lives, more than 100,000 Obama for America canvassers knocked on more than 7 million doors and twice as many volunteers called voters to make sure they got to the polls.”

A detailed accounting of the principles of this approach to organization-building can be found in the excellent publication from the New Organizing Institute- Campaigning to Engage and Win: A Guide to Leading Electoral Campaigns.

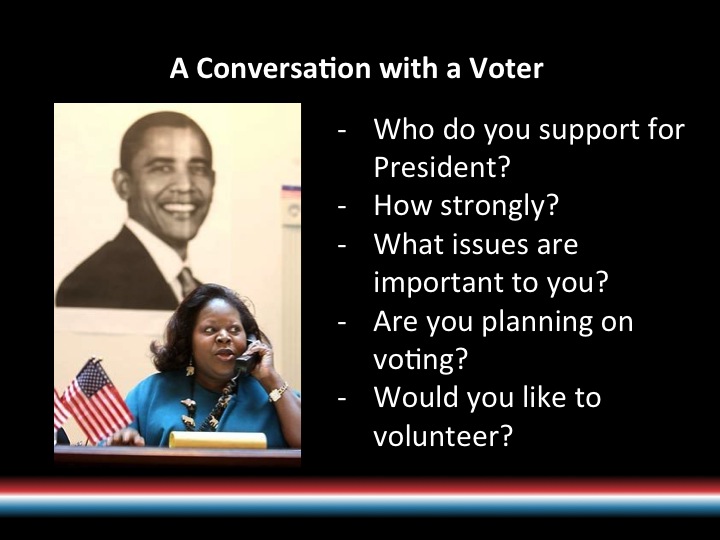

By the summer of 2012 our ground effort was in full swing. Our organizers and volunteers were encouraged to tell their own stories- why are they giving up their Saturday afternoon to make calls for the President? What issues personally resonated with our volunteers and motivated them to get involved?

This helped drive more engaging conversations and encouraged our team to build relationships with voters – not just deliver talking points.

Cold-calling is never easy, but it’s the currency of engagement. The American electorate is more culturally heterogeneous now than it has ever been and having a conversation with a family of first and second-generation immigrants from the Middle-East is not likely to bear much resemblance to a conversation with a White college Freshman with centuries of roots in the country. These cultural considerations are no reason not to engage voters directly. On the contrary these diverse backgrounds are the fuel that gives shape and purpose to political engagement.

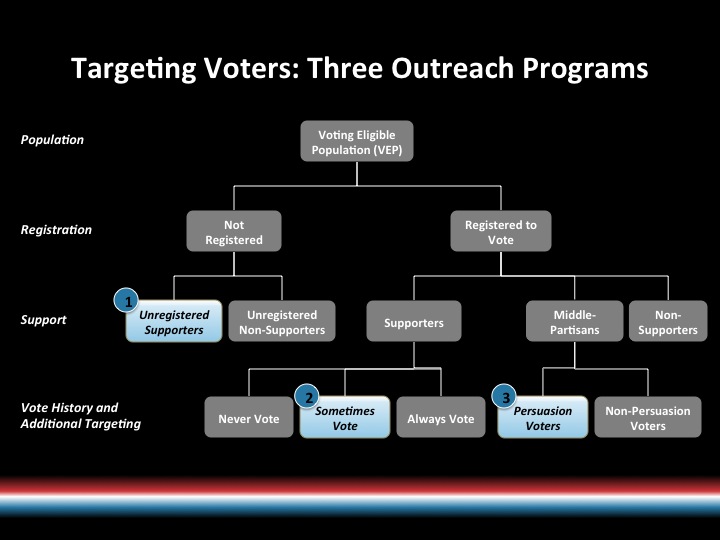

There are three reasons a campaign would expend resources on a voter: to register them to vote, to persuade them to vote for our candidate, and to mobilize them to cast a ballot.

From top to bottom, our Tech, Data, Analytics, and Field operations were all designed to define these segments, identify target areas or individuals, and execute the appropriate program based on our intelligence.

Much of the conversation about political campaigns often revolves around “independent” or “swing” voters, but persuasion is just one element of a winning campaign.

The path to victory is different for each state. In a state like Michigan, working to increase Democratic turnout can be enough to carry the state for a Democratic candidate.

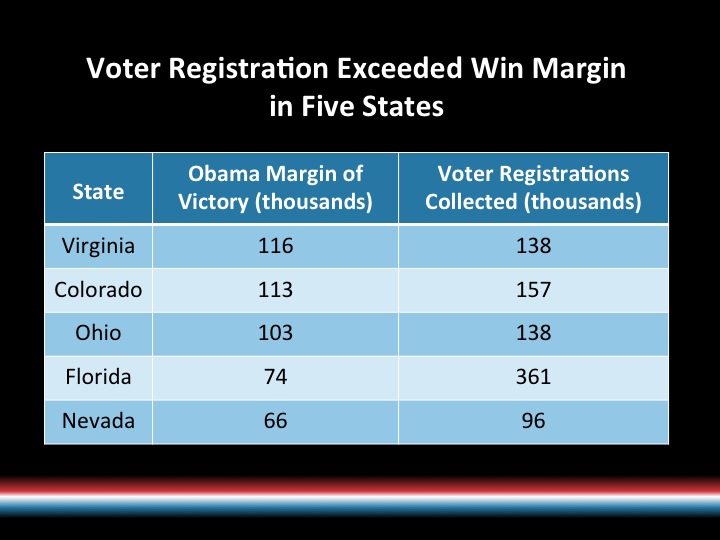

In a state like Florida, however, we needed to run aggressive programs to register new voters, persuade, and turnout in order to win.

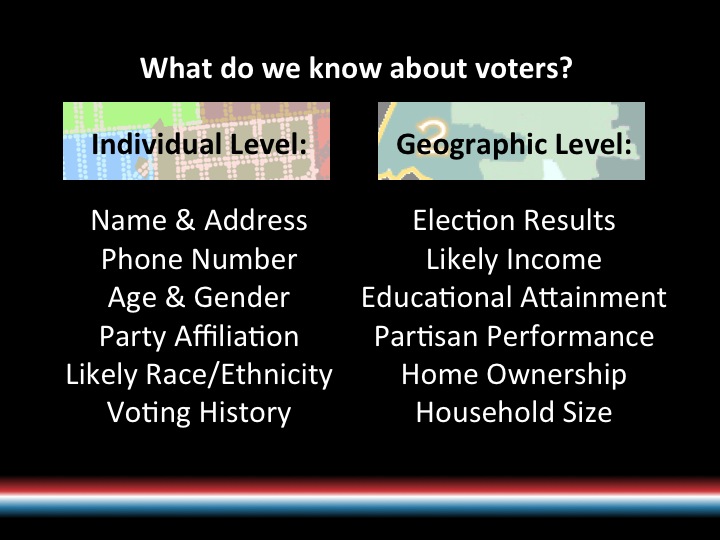

Our efforts to identify who we should target were only as good as the data we started with. In the US, publicly available voter files contain much of the information campaigns need to start targeting.

Individual-level information from these voter files was supplemented with our internal finance and volunteer databases and consumer data vendors. This was then combined with geographic-level information from the US Census to establish a high-confidence profile of targeted precincts and individuals.

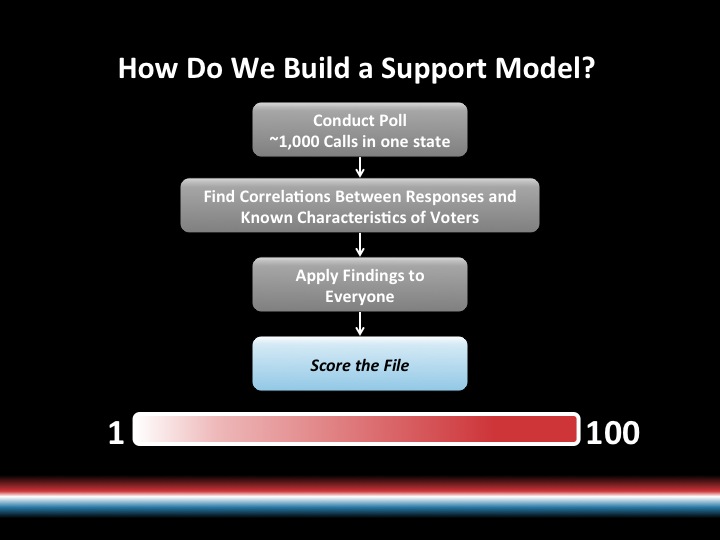

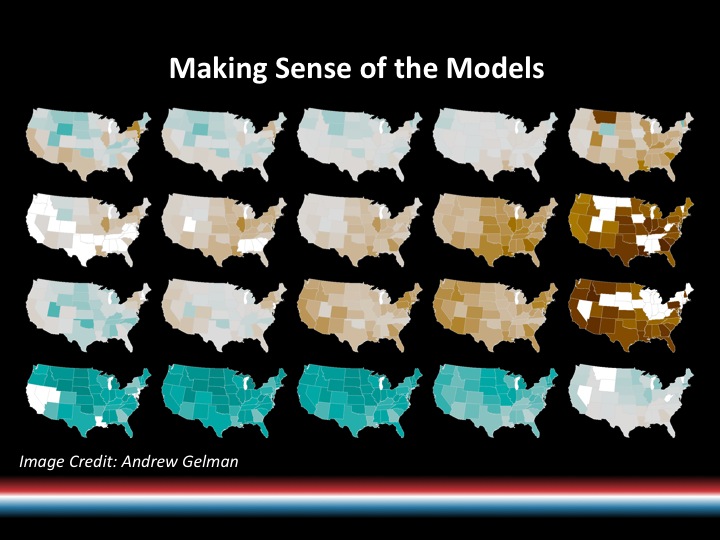

Our analytics team used the combination of individual and geographic-level data to build statistical models. We call these “voter contact models.” A model is essentially an opinion poll that has been extrapolated to the individual level.

These models helped us identify our target segments: voters who would be likely to support Obama, for instance, and might fit into our turnout program. These models were added to individual voter records as a “score” between 1-100.

For more on how the Obama campaign built and used statistical models, the LA Times has a good overview in this article and journalist Sasha Issenberg has an in-depth, three part series here.

A voter contact model is just a tool- it can be interpreted and used in many different ways. Our Data Directors worked with other members of the state leadership team to determine how to implement these models. Do we want to focus more of our resources on turnout or persuasion? What about voter registration?

How many volunteer hours do we think we can count on over the summer? How many actual conversations with voters can we have? The result of these calculations was our voter contact list.

Data doesn’t end at voter files and statistical models.

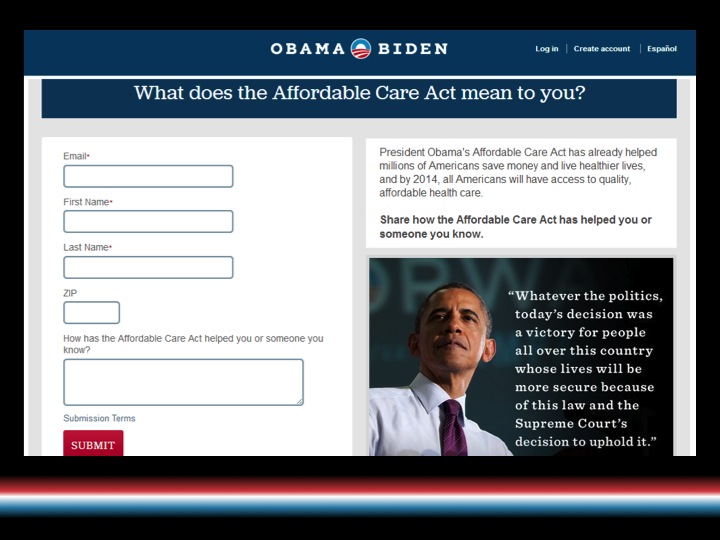

This video, produced in-house by the Obama campaign, tells the story of Stacy Lihn and her family. Her daughter was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect and, despite having health insurance, was already halfway to her “lifetime limit” at the age of six months. The Affordable Care Act eliminated those lifetime limits.

Stacy shared her story with the Obama campaign by way of an online form. Hers was one of thousands of stories collected not only through this form but also shared with organizers and volunteers in conversations all over the country.

We were able to make the Lihn family a part of the narrative fabric of the campaign.

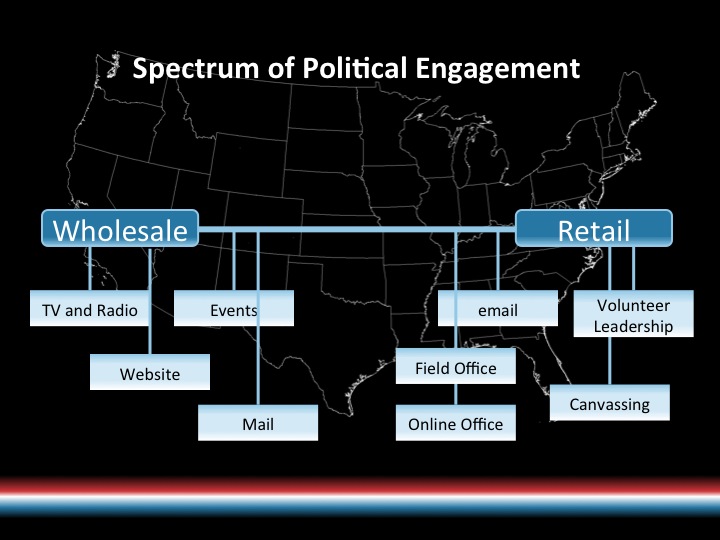

Campaign activities can be thought of as existing on a spectrum from more wholesale to more personal, or “retail.” At one end of the spectrum are mass-marketed approaches to campaigning: TV ads, large events, traditional websites.

Things get more personalized with more targeted approaches- local campaign offices, targeted mail and email campaigns, and, at the far end of the spectrum, building relationships with individual voters and empowering volunteers with leadership roles within the campaign structure.

The terrain of political engagement isn’t flat, however. Campaigns make deliberate decisions about how to structure their outreach and this naturally has consequences for the nature of the relationship voters have with the campaign.

When a voter calls a campaign office to ask a question, or when they indicate they are interested in a particular issue on a web form, are they dispensed a position paper or do they get a call back from an organizer? Are they invited to come to an office opening or an event or do they simply get to enjoy the promise of dozens of fundraising emails?

No campaign needs a billion dollars to engage voters, to ask them for their story, to engage them as a whole person.

Any campaign can build a Data program that values the qualitative over the quantitative, that values interpreting information over amassing it, and that empowers local staff and volunteers to solve problems and engage voters using their own guile.

—

Ethan Roeder is Executive Director of the New Organizing Institute

This post was edited by Yussi Pick.

Don’t blame the UK’s stagnation on the Eurozone – the evidence doesn’t stack up

One constant theme in the Chancellor’s speeches has been that his austerity would be working wonderfully if it wasn’t for those pesky foreigners. There’s one problem with this: if they are holding us back, how come they’re mostly doing better than us?

There’s no mystery about why the Chancellor is looking for scapegoats.

Last week’s preliminary estimate for GDP (the one that showed 0.6% growth since the previous quarter) revealed that, between the second quarter of 2010 and the second quarter of 2013, the economy had grown a magnificent 2.1% – about a quarter of the trend rate.

The chart below shows GDP growth rates (comparing each quarter with the same quarter a year before) and the government ought to be very embarrassed by it.

Within six months of the government’s election, our economic growth had been cut off, with a downward trend that may (let’s hope) have come to an end in the most recent figures:

So you can understand why Mr. Osborne would like us to believe that it would have been higher if it hadn’t been for depressed European and US economies, making it difficult for us to export to them.

And that is the line he has stuck to.

A year ago, Mr. Osborne told us he was exasperated at the failure of Eurozone government to sort out their problems, which “would do more than anything else to give our economy a boost.”

Delivering the Autumn Statement, he told us “we face a multitude of problems from abroad. The US fiscal cliff, the slowing growth in China. Above all the eurozone, now in recession.”

By the time he got to this year’s Budget in March, he worried that the problems Cyprus was experiencing showed that “the crisis is not over, and the situation remains very worrying.” In June, it still wasn’t over, and his speech on the Spending Review returned to the theme:

But while we’ve been acting, the challenges from abroad have grown. A eurozone in crisis. Rising oil prices. The damage from our banking crisis worse than anyone feared. And the truth is Mr. Speaker, we have to deal with the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. So this country has to continue to make savings.

And, if those Eurozone economies and the USA had been growing more slowly than us, there might have been something to that line. But that isn’t the case. In the table below I’ve used OECD data (*) for GDP in the second quarter of 2010 and the first quarter of 2013 (there is no Q2 2013 data for most countries) and calculated how much it has grown or shrunk for the UK, all the Eurozone countries the OECD covers and the USA.

If slow growth abroad is holding us back, why have our first, second and third largest export markets grown faster than us? I’ve also included a column giving each country’s share of UK exports in 2011 (the most recent I could find, using HMRC data).

You can see from this that, while there is a group of Eurozone countries that has done worse than us, they only account for 15% of UK exports.

Problems in the Eurozone won’t have helped the UK’s recovery, but we can’t make it the main explanation for our stagnant economy.

We need to talk about the British arms industry, and its exports

by James Elliott

Wednesday’s Independent broke the ‘arms-for-dictators‘ splash, revealing the embarrassing story of our government approving arms sales to 25 out of 27 of the countries on its human rights blacklist.

Sri Lanka, China, Belarus and Zimbabwe received weapons, along with Russia and the West’s arch-nemesis in the Middle East, Iran. Most of the £12bn cache was sold to Israel, although it was almost entirely cryptography and software.

Whilst news, this story isn’t new. Recently I wrote about David Cameron’s propensity to jet off with arms dealers, seemingly selecting his destinations based on who had the worst human rights records. Kazakhstan and Saudi Arabia are just two dictatorships he has helped arm, whilst demonstrators in the Arab Spring where repressed with British tear gas,and demolition charges sold to Bahrain and Egypt.

Labour have nothing to be smug about on arms and human rights. After Thatcher and Major had armed the genocidal General Suharto, New Labour continued being his major weapons supplier. Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian regime, potentially the next target of that awful phrase ‘humanitarian intervention’, was invited to an arms fair, whilst David Miliband had to confess British weapons were used on Palestinians in the 2008-9 Gaza massacre.

Douglas Alexander last year wrote in The Guardian that Labour would get tough on arms exports, but given he didn’t even mention Israel, and since recently gave a hawkish speech for the Labour Friends of Israel, there is nothing to suggest he won’t repeat David Miliband’s error.

The terrible excesses of the arms trade will continue until the power to decide who does and does not get British arms is taken out of the hands of politicians, who are liable to lobbying and corporate manipulation, as the Sherard Cowper-Coles and BAE affair exemplified so well.

We need some kind of extra-parliamentary judicial body, either the UK Supreme Court or a new human rights and humanitarian law court, to scrutinise the arms industry. Where weapons are sold with the foreknowledge that they will be used for crimes, which at the moment means business as usual for the arms trade, judges, not politicians, should adjudicate.

We should treat corporate complicity in international law violations, war crimes and human rights abuses for what it really is: criminal behaviour.

Politicians who approve the licenses should be drawn in too. I doubt we would see Cameron flying around the Middle East selling weapons to dictators if he knew he would face a judge’s wrath, or even an arrest warrant, when he got back.

This policy requires a prime minister of some vision and certainly a little courage, but their legacy could be the first genuinely progressive foreign policy of this once imperial nation.

—

James Elliott writes for the Huffington Post. You can read his blog at jfgelliott.com and follow him on Twitter @JFG_Elliott

Media myths about the Greek public sector are still used to push crippling austerity

by Tom Gill

The Greek government last night passed a law firing thousands of public sector workers.

Twenty five thousand workers – mainly teachers and municipal police – will be placed in a layoff scheme by the end of 2013. They have eight months to find another position or get laid off.

Why? According to Reuters, “Greece’s public sector is widely seen as oversized, inefficient…”

Lazy journalism, once again. What are the facts? Greece’s public sector may well be relatively inefficient, although there is little reliable data on public sector productivity and the press rarely if ever quote hard evidence. But the charge that it is oversized is nonsense.

The number of state employees in Greece is below the EU average. According to the OECD, “Greece has one of the lowest rates of public employment’ among advanced economies, with general government employing just 7.9% of the total labour force in 2008. Across the OECD area, the share of government employment ranges from 6.7% to 29.3%, with an average of 15%.”

This report also notes that compared to other OECD countries, the Greek government spends a much smaller portion of resources on education (8.3% vs. 13.1%), and only some of that is down to a smaller school-age population. So why are teachers targeted for lay-offs?

Not that there isn’t obvious waste in government expenditure. For example, Greece spends above average – in the EU it is about 2% of GDP – on defence. According to The Guardian, “No other area [of spending] has contributed as heavily to the country’s debt mountain. If Athens had cut defence spending to levels similar to other EU states over the past decade, economists claim it would have saved around €150bn – more than its last bailout. Instead, Greece dedicates up to €7bn a year to military expenditure – down from a high of €10bn in 2009.”

But the Troika is using international loans to force through more cuts to the public sector workforce.

At a time when the private sector is not hiring, this will add to total unemployment. This in turn will further hit the economy as in Greece which is heavily dependent on household spending (74% as against 58% in Germany, according to the World Bank.

More misery, in short, for a country now in its six year of recession and where unemployment is expected to rise to 28% by the end of next year, according to forecasts published this week.

With help by from the media, the myths perpetuate, and Greece burns.

—

Tom Gill is a London-based writer who blogs at www.revolting-europe.com on European affairs from a radical left perspective.

NHA Party unveil 10-point plan to protect the NHS

Suspending the closure of A&E departments, repealing the government’s NHS reforms and reinstating the NHS as the preferred provider of health care are among the measures in a 10-point plan announced this week by the National Health Action Party.

The new political party, launched by doctors and health care professionals, will be fielding candidates at the 2015 general election.

The say the 10 point plan is to re-instate, protect, and improve the NHS.

1. Repeal the Health and Social Care Act to restore the NHS as a publicly delivered and publicly accountable comprehensive healthcare system. The most practical solution is to back Lord Owen’s NHS re-instatement bill, which we fully support.

2. Re-instate the NHS as the preferred provider of healthcare. This will protect the NHS as a public service by minimising private sector takeover of NHS services

3. Abolish the Private Finance Initiative (PFI). Renegotiate and buy out contracts at realistic value.

Any publicly owned banks must cancel PFI contracts before re-privatisation. Stop and reverse the outsourcing of clinical and support services related to PFI projects.

4. Moratorium on A+E and hospital closures. Any reconfigurations must be clinically, not financially driven, and must show they have won public and professional support for alternative, improved services

5. Reduce the Department of Health’s reliance on expensive external management consultants who have too much influence on health policy. Instead the DH should re-engage with the representative bodies of frontline NHS professionals, as well as patient groups, to develop and plan future NHS policy in the most clinically effective and sustainable manner

6. Ensure evidenced-based adequate staff to patient ratios in order to maintain safe, effective, and high quality patient care

7. Improve accountability and transparency of the NHS by: a) bringing back Community Health Councils (CHCs) and combining them with external peer review of hospitals and GP practices; b) Reviewing and strengthening the NHS complaints process and improving the ease of access, and protection for whistle blowers

8. Use the purchasing power (monopsony status) of the NHS to improve NHS procurement practices in order to reduce costs of drugs, medical devices and general supplies.

9. Strongly focus on dealing with the social determinants of health, such as poverty, wealth inequalities, unemployment, poor housing, social exclusion, lack of child care etc. Prioritise public health and social care.

10. Exempt the NHS from the EU/US Free Trade Agreement, which otherwise threatens to open up our healthcare system to irreversible privatisation by large multinational corporations

Longer term plan – abolish the destructive, divisive and expensive purchaser-provider split

More info on their website: www.nationalhealthaction.org.uk

The Rohingya Muslims in Burma are on the verge of facing genocide, and we can help stop this

Genocide is not a term to be bandied around willy-nilly. The whole point of the UN’s post-war Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide is that it marks out genocide as being on a different scale of evil from, let us say, mass indiscriminate killing undertaken in the pursuance of state expansion.

So even though I’ve followed, for a number of years now* the mistreatment and murder of the Rohingya, a Muslim minority living principally in the Burmese state of Rakhine, I have been reluctant to see the ongoing atrocities as genocidal.

Until now.

Developments in the scale, manner and motivation for the killing of Rohingya people now seem to meet many if not all of the pre-conditions for a coming genocidal phases. Using Gregory Stanton’s Eight Stages of Genocide as a useful starting point, it is fairly easy to see that the first six of these have fallen or are falling into place:

Classification: the Burmese authorities, in collusion or at least in fear of a now rampant militant Buddhism, have overseen the development a popular conception of Burma as a bipolar society – Buddhist Burmese vs. Muslim minority (cf. the artificial disaggregation of Tutsis from Hutus). This has intensified in recent months as Muslims from outside the Rohingya community and beyond Rekhane state have been targeted, increasing the bipolarisation. This is not to say that the Christian minority in Kachin state have not also suffered terribly, but increasingly it is the Muslim minority which seems to be being portrayed as the sole enemy within.

Symbolization: The stripping of citizenship (and thereby travel) rights and the herding of Rohingya communities into ghettos, where they can be increasingly marked out as ready and waiting for killing. This goes alongside the narrative of the Rohingya as fairly recent illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, despite the clear evidence of settlement in the pre-colonial period.

Dehumanization: An important phase, in which the normal revulsion against murder seems to be being overcome by significant sections of the population, for example in this episode of the merciless killing of teenagers, in which an exhortation to “Burmese courage” propels a group of people to do the hitherto unthinkable. Here it would seem, the ‘moral’ authority provided by extreme ‘969 Buddhism’, under the guidance of ‘Bin Laden Monk’ Ashin Wirathu, is of importance.

Organisation: The all-too-common process of state denial, whereby the state at the very least turns a blind eye to atrocities carried out by local militias, seems to be developing in Burma. In Burma, this local organization seems to be in the hands of the religious community, though there are some doubts as to whether some of the leaders – including the one able to drive heavy machinery – are actually monks.

Polarization: For example, a law effectively outlawing intermarriage has been drafted by extremist Buddhist groups, with the apparent approval of the state.

Preparation: As noted, the herding of Rohingya communities into barely liveable ghettos, sometimes “for their own safety” has begun in earnest, in a process which makes later killing more ‘manageable’ but at the same time furthers the dehumanization process.

In short, all the warning signs that a truly genocidal phase is coming, and maybe coming soon, are there.

The deepest irony, perhaps, is that all this is happening as Burma moves seemingly inexorably towards democracy, and as Western nations (and China) start to invest/extract heavily.

It is surely with the narrative of a new, open and free Burma that its Prime Minister is due to arrive in London and Paris this month for talks with Cameron and Hollande. Back home, the (ex-) Junta, and arguably even Aung San Suu Kyi, are focused increasingly on how they might best build up their vote for the approaching elections, and it seems increasingly unlikely that they will do so by appealing for tolerance towards the Rohingya community.

But genocide is not inevitable. Outside attention can create the impetus for even a weak state to step, especially if it fears losing the foreign investment and allied political legitimacy it craves, and in this case may help to embolden the opposition, who do appear strangely quiet.

So what can we do as bystanders? Well there’s a useful petition, asking the European leaders that meet the Burmese President to go beyond the usual platitudes about welcoming democracy. Please do sign it.

Perhaps more importantly, we might remember the ‘never again’ commitments of our governments when the scale of the horror in East Pakistan, then East Timor, then Rwanda & Burundi became apparent, and Srebrenica appeared on our screens, and ask our own elected representatives about what they can do about evil on a scale beyond mass murder.

—

To follow developments, I recommend French journalist @sophieansel (in English and French) and @voicerohingya as good starting points, though the New York Times also keeps a good eye on things.

Why I support (limited) western intervention in Syria

I doubt this post is going to change many minds, but its worth explaining my position anyway

Imagine a situation where your neighbour is a drunk man who comes home and beats his wife every day. You can hear her screams and unsuccessful attempts to fight him off and feel powerless. The police are unable to intervene and she carries on getting beaten and raped. Do you sit by and do nothing because it’s not happening in your house? I wouldn’t.

Foreign policy isn’t exactly the same, but I’ve always believed we should intervene in other countries if a humanitarian crisis is taking place. I’m not an isolationanist though I recognise that governments don’t always have humanitarian concerns at heart when they interfere in other countries.

Syria is not Afghanistan, or Iraq or…

Would you support an arms embargo on the Palestinians and deny them the right to defend themselves against Israel? I wouldn’t. I bet most of you wouldn’t either.

Ahhh, but Syria is different – you say. You’re right, it is. It is also different to Afghanistan, Iraq and other recent conflicts. Which is why I don’t buy the argument that this is like Iraq (which I was vehemently against) or other conflicts.

This is a minor intervention

The US is not invading Syria (I would not support that) – at most it is offering small arms and ammunition, and perhaps establish a No Fly Zone.

The aim isn’t to flood Syria but increase pressure on Assad and Russia. It is a warning shot with the aim of pushing them to negotiate. At the very least it would make it harder for Russians to feed Assad bigger missiles. This is a VERY limited intervention with support from neighbouring Arab countries such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Egypt. I repeat: it is not Iraq.

Chemical weapons

There’s a reason why the ‘red line’ was chemical weapons, not the 90,000 dead. The UN (and US) aim is to demand action when chemical, biological or nuclear weapons are used, in the hope that it sets a precedent and dissuades countries from using them despite availability. If no action is taken at all and Assad sees this as a bluff, it could open the way for more chemical weapons being used.

How many is too many?

There is a real danger that unless Assad willingly abdicates or transitions Syria to a democracy, the civil war could go on for years. Another 100,000 could be dead. Instead, in an effort to end the stalemate, we have a limited intervention by Nato forces, working in conjunction with other Middle Eastern countries, to put pressure on Assad to step down. To compare this with the bombing of Iraq or Afghanistan isn’t just absurd but actually ignorant.

How many dead people is too many? A quarter of a million people dead? Half a million? A million? Would you oppose any intervention at any cost to human life? I wouldn’t. I think 90,000 is far too much. I also think it should be a limited intervention, and evidence of chemical weapon usage fully explained. I don’t think our govts should get a blank cheque, but neither should we sit by and watch tens of thousands get slaughtered.

Why southern Europe has a bleak future: the youth are emigrating

I wrote a post the other day that caused something of a stir. I argued that migration of the young & skilled from southern European countries could mean that those left behind face a very bleak future. Let me explain a bit further.

I am emphatically NOT arguing that there is anything intrinsically wrong with young, skilled people leaving in search of a better life elsewhere. Migration benefits both the migrants and the receiving countries. Immigration is a GOOD thing for countries that have ageing populations and skills shortages – as most Western countries do.

But where people can freely move to other countries, the sort of ‘internal devaluation’ that forces down wages in search of ‘competitiveness’ inevitably causes migration when the same jobs in Greece and Germany pay vastly different wages. Unfortunately it is this sort of ‘internal devaluation’ that has been forced on the Eurozone periphery because their membership of the Euro prevents them from devaluing their currencies vis-a-vis their main trading partners, which is the usual means by which countries restore competitiveness.

Traditionally, young migrants send money back to their parents. But in the West, with pension and healthcare systems that support the old, the explicit contract between children and parents is weakened. I don’t have evidence to support this but I think that young migrants are much more likely to send money home when there is little state pension or healthcare provision in their country of origin. If they believe that the state will support their parents, they may not send money home.

The problem is that the people left behind are older, less able and lower skilled, which makes these countries less attractive to businesses. After all, why would a business choose to locate itself somewhere where the local workforce is ageing and poorly skilled? So businesses would go elsewhere too. That would cause GDP to shrink further.

The population’s need for state support would actually increase as it ages and gets sicker, but tax revenue would fall as working people and businesses leave. That adds up to long-term decline and a growing burden on the state’s finances.

And old people and long-term disabled don’t generally pay taxes. So where will the taxes come from to support the welfare systems that these people depend on?

There is one final ingredient in this poisonous mixture. Most of these states are already highly indebted. With a growing burden on their healthcare and pension systems and falling tax take due to GDP decline, their debts can only get worse. The fiscal compact gives primacy to debt service over maintaining public services. As I see it, therefore, these states will eventually be forced to dismantle their welfare systems – the pensions and healthcare required by their ageing populations – to avoid debt default.

Eventually, I suppose, the old and the unskilled will also leave – if they can, and if any country will receive them. For although the European Union is in theory committed to the free movement of people, I wonder how real that commitment would turn out to be in the face of large-scale migration of pensioners and benefit claimants from the Eurozone periphery. I suspect that free movement of people might turn out to be another of those European laws that are binding in good times but illusory in bad.

Therefore as Krugman said, the combination of labour mobility with internal devaluation and lack of fiscal union in the Eurozone is potentially lethal.

There is no possibility of recovery for countries caught in the deadly embrace of high public debt and youth migration. For them, “internal devaluation” actually means creeping desertification.

—

A longer version of this blogpost is here.

Why Britain should play an active part in arming Syrian rebels

If the UK government is considering arming Syrian rebels, it should also consider embedding British personnel with rebel forces.

This arms supply method was developed by Fitzroy MacLean in his dealings with the Partisans in WW2. It is accounted for in MacLean’s famous book Eastern Approaches.

The reason for embedding personnel, with our equipment, is partly that we can then be sure who is using our arms, but also in order that we have a relationship and an influence, both now and in post-conflict Syria.

In WW2 the Balkans were just as bloody as Syria is right now, if not more. Whole villages were executed as Nazi punishments. Engaging the Partisans, MacLean would often dissuade them from responding in kind. “A modern country would not do that kind of thing.”

He was reminding them that after the war they would be expected to join the international community, as a nation, not a barbarous tribe. MacLean probably averted a considerable number of massacres and atrocities, but he was only able to do so because he was present.

British influence, of this kind, would be felt by the Syrian rebels, if we were arming and amongst them.

Most of the reports concerning the character of the rebels comes from Turkish and American intelligence in Syria. The problem with this intelligence is not that it is wrong, but that it paints a picture of the rebels unaffected by a relationship with us. They long ago gave up on the west as allies. We have little influence, while Saudi Arabia and Qatar has considerable clout.

My point in describing the MacLean system is to draw attention to the humanitarian benefits, which cannot be replicate by sitting on the sidelines and saying “Nothing to do with us. We’re not responsible.”

Do we achieve innocence through inaction? If a man is drowning and we stand by and watch, are we not responsible for his death, due to our lack of action? If a doctor watches a man die, knowing that the medicine in his bag which could save him, has that doctor done nothing wrong, by his inaction, of has he killed the man by his failure to act?

If the rebels demonstrate themselves as barbarous, while under the influence of the Saudis, are we not at least partly responsible, by our refusal to enter and engage?

By embedding our personnel, we can pick and choose which militia can use our technology.

We can encourage talks and cooperation between factions, acting as honest broker. We can influence a peaceful outcome and avert further tragedy. That is the type of player we should be.

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE