Recent Housing Articles

How Boris keeps selling off chunks of London housing to rich investors

Boris Johnson loves property investors because they help developers build homes. But homes for whom? The reality is that these expensive homes benefit rich investors and developers far more than ordinary Londoners, who are seeing their city sold off chunk by chunk.

Today I asked the Mayor about One, The Elephant, a 37 storey tower block with 284 flats built on council owned land. He signed it off last November, and launched the construction on site this August saying it would “bring quality homes into the area”.

But its studio flats will start at £330,000, and were marketed in Hong Kong and Singapore before they went on sale in London. That price is twelve times the average income in Southwark, and even further from the incomes of residents in the Elephant area.

There is no affordable housing at all, just a contribution towards some affordable homes elsewhere in the local borough of Southwark.

In the officer’s report to local councillors, the reason was clear. If they mixed affordable and private housing together, it would have “significant implications on the values of the private residential properties” – the developers wouldn’t get as much profit because investors don’t want flats next to the hoi polloi of London.

Some developers have actually put separate entrances and lifts in for affordable housing, like servants having to enter via the back door in Edwardian times. But the council officer’s report said the “practical and financial implications” ruled this out.

Elephant and Castle used to be called the ‘Piccadilly of the South’, and at the moment seventy per cent of the residents in the area live in secure, affordable social housing. In the new “regeneration” projects around the Elephant, only eight per cent will be social housing.

Londoners just get crumbs from the property feast, as I argued in a detailed report published last month.

The Mayor should threaten to refuse these applications unless they offer enough affordable housing. He should also lobby for taxes on investors to damp down demand, for a social housing budget big enough to actually meet London’s needs, and for regulation to stabilise private rents.

Foreign money is turning London’s housing market into an unaffordable bubble

According to the Bank of England, each year since 2010, £23 billion of foreign money has poured into the London property market. One would think that this is a good thing for the economy, but most of these foreign buyers have never been to London, or at least have no intention of spending any time here.

It’s all about the preservation of wealth. The residents of unstable oil-rich countries fear the Arab Spring. The residents of China and Russia fear their governments. All are looking for stability. It has become the fashion to “park” money in London. It’s what wealthy people do when they don’t trust the banks, they “park” their money through the purchase of an asset, as a store of value. In this regard, the London property market has become a gynormous piggy bank.

In 2011, Regent Street was valued by The Crown Estate at £2bn. Each year a multiple of over 11.5 times this in ordinary homes is being snapped up. That’s the equivalent, each single year, of Oxford Street, The Strand, Fleet Street, High Holborn, Trafalgar Square, High St Kensington, Old Bond Street, Berkeley Square, Park Lane and Knightsbridge, and more. That’s just one year.

The reason government is doing nothing about this, is because the economy has been so delicate for the last three years, and the question of whether we are in or out of recession have been so finite, that any short term economic activity has been welcomed.

Far from rebalancing the economy, this government are just desperate to fend off the calls for a Plan B. Far from building a long term prosperity, they are trading the benefit of short term finance, for long term misery. This chancellor, who once accused Gordon Brown of being “dishonest” with the British people, is now covering the tracks of his own failure, fully in the knowledge that a future government will be forced to clear up the mess.

The dividing lines between Labour and the Conservative Party is clear. We believe the state has a role to play in building a better society, they believe that the market is supreme in every regard. We believe that government can guide or regulate the market as and when it becomes destructive. They do not.

In this case, the destruction is due to the sheer scale of housing that is being taken out of productive use. The situation has got so bad that even the bankers are being edged into poorer districts. This then bumps the next social class into the next district and so on. In my area of Tower Hamlets, period housing used to be priced at a premium, but as prices push against the ceiling of affordability, the prices of ex-council flats are coming into line with the Victorian terrace.

As prices rise and foreigners become excited by their returns, more money pours into the market causing more housing inflation. If this speculative bubble were caused by the British population then there would be some constraints imposed by the size and the wealth of the native population, however, we are talking about massively greater forces at work.

We keep reading polling that tells us this is not a major issue to the electorate, but that is the reason why Labour should be hammering the message home. Ever since George Osborne’s economic policies failed, we’ve seen increasingly dangerous long-term problems being created by a government who are only concerned with securing their own jobs.

They will continue to do so until the Labour persuades the nation of their folly and creates a consensus for restrictions on foreign purchasing.

How Labour’s plan to tackle the housing crisis will work

In the past six years, both Labour and the Conservatives/Lib Dems have set out policies to tackle the housing crisis. In 2007, Gordon Brown set a target to build 3 million homes by 2020, a goal which was almost immediately killed off by the financial crash. Meanwhile, the Coalition’s policy has been to ask the vested interests for their policy wishlist and then implement it – spending billions on state-backed mortgage guarantees, allowing developers to reduce standards and build fewer affordable homes, allowing anti-development councils to block new homes. Unsurprisingly, this hasn’t worked either.

So why might Ed Miliband succeed where Gordon Brown and David Cameron have failed? The answer is in his revolutionary new approach to the policy development process. In place of grandiose target setting or government-by-vested-interest, Labour’s housing policy has been developed by two groups who are usually shut out of the policy development process – ‘people on low and middle incomes’ and ‘experts who know what they are talking about and don’t have a financial interest in making the problem worse’.

The main features of Labour’s housing policy are as follows. Firstly, a recognition that we need to build more homes at a time when there is a lack of capacity – far fewer firms, fewer workers with skills and so on. Secondly, targeted policies which will make this increase in supply possible – a ‘right to grow’ to stop Tory-run councils from vetoing new homes, new garden cities, and the ‘use or lose it’ policy to prevent landowners gaming the system. For all the hysteria, this particular policy is one backed by filthy communists such as the International Monetary Fund and Boris Johnson. Thirdly, greater housing security for people – from axeing the bedroom tax to reforms to regulate bad landlords and help people who rent privately.

The reason we have a housing crisis in Britain is because housing policy has been dictated by a wealthy, well organised minority, who benefit from house price bubbles and a lack of homes. Meanwhile, the majority who suffer from these policies are less organised and haven’t had a political party for many years prepared to put them first and see off the scare-mongering.

There is further for Labour to go, and in particular it is hard to see how these goals can be achieved unless local councils are given the freedom to borrow to build homes. But in more than a decade of working together with people from ‘Middle England’ and those living in poverty who have been suffering from our dysfunctional housing market, this is the first time that I’ve seen a national political party which really seems to get the problems which they’ve been experiencing and has a credible plan to sort these problems out.

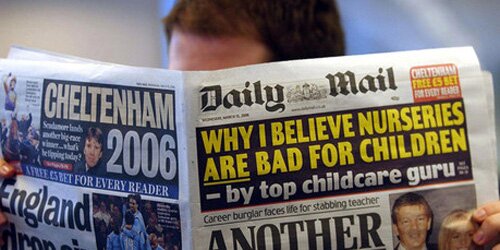

How the Daily Mail twisted housing statistics to blame immigrants yesterday

The Daily Mail have managed again to combine two of their obsessions, migration and housing.

In a highly misleading article last week that suggests migrants are preventing existing residents from getting social or council housing.

Luckily the Financial Times has journalists who know how numbers work and don’t trade in scare stories – I am indebted to @StatsJournalist Kate Allen for alerting me to the data behind Steve Doughty’s nasty little piece.

The claim is that nearly 500,000 council homes (the article clarifies in the text that this includes all social housing) have been allocated (“given” is the term inaccurately used) to “immigrants” (although as Kate Allen points out, the data relates to people born abroad, which stretches from Boris Johnson to many children of armed services personnel) in the past decade.

The real story about housing and migration is this. People born outside the UK are much more likely to live in rented accommodation than people born here, because they are poorer.

Of those living in rented accommodation, most people born abroad are in the less beneficial private rented sector. And what we need to ease the waiting lists for social housing isn’t less immigration, it’s more social housing – we need to build more homes people can afford.

The Mail doesn’t point out that seven times as many people born in the UK live in social housing as those born outside, nor that the predominant form of housing tenure for those born in the UK (33 million to 15 million) is home ownership (among those born abroad, the ratio is 3 million to 4 million – they mostly rent.) One reason why people born outside the UK are more likely to be in social housing than people born here is because they’re poorer, and that’s why they concentrate in the least advantageous forms of housing. There are ten times as many native-born homeowners than foreign-born, eight times as many social renting natives, and just over twice as many native-born as foreign-born private tenants.

It’s also worth noting that the more recent the arrival, the more likely foreign-born people are to be private tenants. two thirds of those who arrived before 1981 own their homes (surprisingly similar to the domestic population), but nearly two thirds of those who have arrived since 2001 are private tenants. One in seven recent arrivals are in social housing, compared with one in six of the native born (again, exactly the same proportion for those who arrived before 1981). Not surprisingly, the longer people live in the UK, the more they behave just like those born here.

However, in one of those ironies of right-wing populist politics that gets people at the Mail chewing the carpet, part of the crackdown on immigration that the coalition Government is presiding over – by making private landlords less likely to rent to migrants – will force more recent arrivals into homelessness, thus triggering the requirement on local authorities to provide them with social housing. So a direct result of the Government crackdown on immigration will be an increase in the proportion of social housing going to migrants!

Five reasons why the government’s Benefits Cap should be opposed

by Matthew Whittley

Last Monday saw the introduction of the benefit cap, the latest of the coalition’s welfare reforms. The cap limits the amount a household can claim in benefits while out of work, regardless of need. The 40,000 families affected will lose on average £93 a week.

Some of the effects will be:

a) It might be possible for some households to scrape together the £14 a week needed to pay the bedroom tax, but those hit by the benefit cap stand no chance. It won’t take long for people to run up arrears and be evicted. Many will end up in temporary accommodation at great cost to the taxpayer.

b) Because of high housing costs, London and the South East will be hit the hardest. Very shortly we will see large numbers of families migrating north, to places with which they have no connection and know no one, because their housing benefit will no longer be sufficient to cover sky-high rents. Some London councils have already relocated residents as far away as Blackpool and Newcastle.

c) By exporting poverty out of the London, this policy will be the final nail in the coffin of mixed communities in the capital. It doesn’t take the foresight of Nostrodamus to fast forward a decade and envisage London looking more like Paris, with the affluent living in the city and the poor pushed out to the suburbs. And we know from Paris, where civil unrest occurs with alarming regularity, that segregation breeds social tensions.

d) It won’t save much money. The Treasury estimates the cap will shave off just £110m a year from a total benefits bill of £159bn. And some believe that to be an optimistic forecast. A leaked letter from the office of Eric Pickles expresses concern that ‘the policy as it stands will generate a net cost’ when the additional cost of homelessness and temporary accommodation is accounted for.

e) The cap will do nothing to bring down the benefits bill because it does nothing to address the root causes of why we’re spending so much on benefits. In London, because rents are so high, housing benefit paid to landlords now accounts for over half of all working age benefits in the city. This is a result of the chronic undersupply of affordable housing. The only way to meaningfully reduce welfare expenditure is to build more homes and create decently paid jobs.

Essentially, it’s a cynical political manoeuvre designed to box Labour into a corner and reinforce the strivers versus skivers narrative by setting the working poor against the unemployed. But we know that at least 70% of those impacted are not feckless scroungers – because they are children. The government’s own impact assessment acknowledges that 140,000 children live in households that will be capped.

And it isn’t fair because it’s a false comparison; it doesn’t compare like with like. The cap is based on average earnings, but a household with a high rent or large family earning £26,000 a year in work – the level the cap is set at – will also be in receipt of benefits, such as tax credits and housing and child benefit, taking their income above £26,000.

The cap is no more than a symbol. For someone who claims to have spent much of the last decade working to alleviate poverty, Iain Duncan Smith should know better than to use the most disadvantaged as a political football.

—

Matthew Whittley is a researcher for a midlands-based housing association and a Labour party member’

The economic case for more social housing across Britain

Rising house prices used to make cheery headlines in the papers. It was associated with economic success. We were all getting richer. If people can afford to pay more and more for houses, then the economy must be getting bigger and bigger.

In truth, the rise in house prices had just as much to do with the easy availability of mortgages, which created an “effective demand”.

As a youngster, I remember how people’s excitement of buying their own council flat infected everyone else. Aspiration amongst the working population must be one of the most important factors to a thriving economy, and it was very much instilled in the east enders in the ‘80s. This is how Thatcher won.

Today we hear commentators speak of the “lack of animal spirits”, referring to an economy which is moribund. Few people are investing lavishly. Few new enterprises are born from a sketch on the back of a beer mat. There’s a general lack of excitement, of inspiration.

The problem is that if we want to fix the problem of over-valued houses, then we would need to supply enough new homes to cause house prices to fall. However, deflation would stop developers buying land for fear of losses through falling prices. House price deflation would effect consumer spending. If people believe they are getting poorer in their assets they will avoid splashing out. How many politicians would choose policies that would have such an effect?

George Osborne must have considered these issues, when he chose to support the buyers, rather than the builders, of new homes. Such is his largesse that his subsidy will include houses up to a value of £600,000. So much for first time buyers.

The problem for the Tories is that they will only look at one section of the housing stock. When considering the solution, it helps to see housing as two separate stocks, with two separate economies. Private housing with it’s market economy, and social housing with it’s demand economy. They are both effected by supply and demand but in different ways. A lack of supply increases prices in the private stock, and waiting lists in the social stock.

The solution is to greatly expand the social because this can increase the amount of available housing without effecting the value of private homes, as social housing doesn’t compete with owner occupation. It would likely bring down private rents but we’re not so concerned about that, because falling rent puts money directly into the pockets of tenants, so the economic effect of rent deflation is more than mitigated.

A dramatic increase in the stock of social housing is an existing policy of Labour. Ed Balls proposes to build 100,000 new homes by providing 20% deposits to Housing Associations, who would raise the rest on the capital markets, using a business plan that combines homes for sale with not-for-profit rent. However, he should probably consider a figure closer to 300,000+ if he really wants to make an impact.

He should also make it his business to sell the economic argument for a greater expansion of social housing to the wider electorate, with a particular emphasis on the likely lower rents, as this provides a benefit to those who haven’t had the good fortune to get a social home themselves.

So it’s not just units that Mr Balls must contend with. He should also turn around the sorry reputation that social housing has developed from past mistakes. That makes a whole other challenge.

One way London Councils could deal with the coming Housing Benefit crunch

by Alex Harrowell

Over the 20th century, the UK made a political choice that we probably never articulated as such.

That is, we decided that the huge expensive city in the lower right-hand corner of the map had to remain a proper city, rather than shipping out its working class to a concrete jungle on the M25 and giving over the centre to the role of a dead museum, sorry, an exciting retail and heritage offer for high-value tourism, and the City and the East to the banks.

At the same time we decided that the outward sprawl had to stop, halting at the green belt. The solution, up to the 80s, was to make housing in the major cities into a public service. Since the 1980s and the key decision to sell the council properties accumulated up to then, the policy changed; instead of taking housing out of the market, we would instead subsidise it. As Tory minister Sir George Young said, housing benefit would take the strain.

Now, the strain will no longer be taken. Local housing allowance – it’s housing benefit but for people in private rentals – is to be drastically cut.

If the tenants can’t pay, they will get the stick. Councils are actively planning to rehouse over 100,000 people outside London.

Of course, faced with this prospect, people will try to survive somehow. On the tenants’ side, some of them will try to disappear in the black economy and tolerate back-garden sheds, friends of friends’ sofas, or perhaps squat in repossessed property rather than be shipped away from their jobs. (Yes, their jobs; housing benefit is mostly paid to people in work. Surely I don’t need to say this.)

On the landlords’ side, they will tell themselves that of course they can find new tenants. They will juggle financing between properties, personal loans, their credit cards, etc.

But there is a solution. Under Eric Pickles’ Localism Bill, councils get to keep their income from rent rather than giving it to the Government.

So, let’s buy the houses, quick. I propose that the London Labour councils, and indeed any others who want to join, launch a jointly-owned company to buy up the BTLers’ property and to manage it as social housing. We could organise this via London Councils itself, as it is now Labour-controlled.

How much is that again?

There are 52 weeks in a year, 133,000 households claiming, so that estimates the flow of housing benefit into rents for the people involved at £2.3bn a year. That’s quite a lot of money. There’s also a £2bn “affordable housing” fund controlled by Boris Johnson we might bid for.

Councils can borrow money from the Government at a 2.8% interest rate, being the rate the Government can borrow for 10 years plus 1%. This isn’t actually all that good. There is an enormous demand for safe assets that actually pay a coupon at the moment.

Some councils, therefore, have decided to issue bonds on the open market instead. At 2.5% for 10 years, the stream of housing benefit would be enough to pay off a £22bn bond issue.

This isn’t a new idea. In the 1970s, a lot of rental property was bought up by London Labour councils’ housing departments and they’ve still got more of it than you might think.

—

A longer version of this piece is at Alex Harrowell’s blog.

Welfare spending is the most important infrastructure investment we can make

At the Autumn Statement we were told that the Chancellor is increasing spending on infrastructure whilst cutting spending on welfare. Such statements are confusing “infrastructure” for “lumps of rock”.

There are two reasons that you would increase spending on infrastructure. The first is that you believe that the spending itself will be good for the economy: the money will create jobs, the newly employed people will buy new things, shops will employ more people, etc.

The second reason might be that you believe that the underlying framework of your system could be more efficient. The classic example would be that late trains cost people time working, so you invest in better train lines.

However, in practice, I see very little notable difference between what Osborne sees as ‘welfare’ and what he sees as ‘infrastructure’ – other than who it is for. What the Chancellor calls infrastructure, I could call corporate welfare.

Let’s take a specific example: the Treasury is going to pay to upgrade our broadband network. They are doing it so that businesses can have access to faster internet. If the state didn’t pay for this, then these companies, if they really need it, would eventually arrange it themselves. So this is just a whacking great subsidy to them.

And you say “welfare”, I say “social infrastructure”.

The basic underlying framework of our society is not just roads, railways and wires. More important than any of these are the institutions which make our civilisation. And the welfare state is key to this.

If the public sector spends less time caring for old people, then this often means that relatives (almost always female relatives) end up taking on those caring responsibilities. Now, what costs the economy more hours of labour – a late train, or the need to care for a sick elderly relative? Social care is as much a piece of economic infrastructure as are train lines or high speed broadband.

Likewise, if we cut social services for young people, then we see a huge financial cost to society – both in the short term in increased crime rates, and in the long term in a less well educated, less well adjusted generation growing up.

There is no particular economic reason to cut spending on social infrastructure and increase it on physical infrastructure – other than an ideological opposition to the welfare state.

——

A longer version is at Bright Green Scotland.

The end of rented social housing in London?

Proposed changes by the Mayor of London to the ‘London Plan’ signal the death of social rented and family housing in London, says a key Labour Assembly Member.

The Plan is the overarching planning document for London, which amongst other things, sets guidelines that determine how much social and family housing will be built in London.

Under the current funding regime social housing is not currently delivered by the Mayor, it is delivered by the 32 London Boroughs.

Labour’s London Assembly Planning spokesperson Nicky Gavron says that under the proposals being debated today, Boris is trying to stop developers and housing providers from building social rented housing.

He is attempting to do this by preventing social rented housing from being included in each of the 32 London Borough’s plans.

This runs counter to giving local communities more power over what happens in their area.

Nicky Gavron released a statement today saying: “Boris has already said he will give no money to build new social rented housing. It is disgraceful that he is trying to use the planning system to block local councils from finding ways of funding future social housing building.”

“This is a direct attack on localism and giving local communities the power to decide what happens in their area. The Mayor’s policies will hit low income families hard and dismantle mixed communities. He is exacerbating the runaway housing crisis that is driving up the cost of living in the capital.”

Ten myths about the housing benefit reforms in London

Myth one: housing benefit claimants are all lazy scroungers

Ministers from both the previous and current government have argued for housing benefit caps by saying we shouldn’t help people to live in houses “that working families could never afford”. In fact, 39% of housing benefit claimants in London have jobs, and many others are retired, caring for children, sick or disabled. In the last two years an extra 52,000 working people have started to claim housing benefit in London, probably connected to the fact that private rents have risen far faster than the minimum wage, which has only crept up by 5%.

Myth two: the rising housing benefit bill was caused by greedy tenants

In the lead-up to the 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review the papers were full of stories about benefit claimants living out of mansions in expensive parts of London. But even then there were only 139 families in London receiving over £50,000 in rent a year out of over 800,000 benefit claimants. Only 4% received more than £20,000 a year, according to the DWP. There were another 243,000 households estimated to be hit by the cuts who were receiving less than £20,000.

Myth three: the rising housing benefit bill was caused by greedy landlords

Analysis by the Department for Work and Pensions found that 70% of the rise was due to more claimants, while only 13% of the rise could be attributed to landlords increasing rents to get more out of the system. Figures used by the Government to suggest that housing benefit has driven up rents turn out to be extremely shaky, based on unrepresentative samples. Since the caps and cuts to housing benefits were introduced, rents have risen far above inflation in London. The causes are complicated – high demand, low supply, short term rental contracts stoking up a volatile market, and many other factors. But benefits aren’t the primary cause.

Myth four: low paid workers could move to cheaper parts of London

It sounds fair, but there isn’t a single borough in London where a cheaper (lower quartile) shared room in a flat would be affordable for a minimum wage worker. Private rents are simply too high for low wage workers. Even on the London Living Wage of £8.30/hour, renting in a flatshare in most of inner London would take up more than the standard definition of an affordable rent – 35% of take-home pay, leaving the rest for council tax, bills, travel, food and leisure.

Myth five: there are plenty of cheaper homes about

In theory the cheaper 30% of homes in a “broad market rental area” should be available to claimants. But in July the Hackney Citizens Advice Bureau did a snapshot survey of 1,585 properties to let in their borough. They found that there were only 142 homes that fell within the new benefit caps, 9% of the total. To make things worse, most of the landlords they spoke to wouldn’t let their properties to benefit claimants, leaving people chasing only 14 homes in the entire borough, less than 1% of those on the market. Research by the Chartered Institute of Housing published in January predicted a similar situation this year across London as cuts bite. For example, they calculated that 17,000 people would be chasing 10,000 properties in Croydon.

Myth six: this is the only fair way to reduce the benefit bill (part one)

Rather than cutting benefit payments, we could reduce the housing benefit bill by reducing rents. Unfortunately the Mayor has ruled out even looking at private rented regulation of the sort used in most other European countries. Another option is to build more social housing, which the Mayor’s housing advisor has said would “clearly help reduce the housing benefit bill”. If we could move every private tenant on housing benefit across the UK into council housing overnight, the lower rents alone would save the Exchequer £2.7bn in housing benefit payments.

Myth seven: this is the only fair way to reduce the benefit bill (part two)

Another way to reduce the benefit bill would be to help more people find work, and to ensure that they are actually paid enough to cover the rent. Using my interactive London Rents Map, you can see that a worker on the National Minimum Wage of £6.08/hour cannot afford a cheaper (lower quartile) room in a shared flat in any borough in London. But if they were paid the London Living Wage of £8.30/hour then fifteen boroughs would become affordable.

Myth eight: social tenants enjoy expensive subsidies as well

The recently departed housing minister suggested that social housing should be rebranded as “taxpayer subsidised housing”. But in recent years council housing has actually been in surplus, making a net contribution of £113m to the Treasury in 2009/10. The main subsidy is the grant used to cover part of the cost of building the homes, but that is more than made up by rent payments and the reduced benefit bill. If all those social tenants receiving benefits were to rent privately it would cost an extra £5.3bn a year in housing benefit payments.

Myth nine: the cuts are helping

When this Government came to power they vowed to cut the benefit bill by nearly £2bn by 2015. But since announcing their cuts and caps the bill has actually gone up by £2.5bn, largely because of the growing number of working households who need to claim the benefit to keep a roof over their head.

Myth ten: the Government’s housing agenda will save money

Instead of building lots of social housing or raising the minimum wage, the Government has actually cut investment in housing and decided to raise rents. The new London affordable housing budget for 2011-15 represented a 66% cut in the annual grant compared to the 2008-11 funding. But the Mayor still hopes to build a similar number of homes each year as he did with the previous, much larger grant. Rents will rise to square the circle, meaning that more tenants will be dependent on more housing benefit payments to keep up. Even the Prime Minister had to admit that this contradiction could increase the benefit bill.

—

This document sets out my individual views as an Assembly member and not the agreed views of the full Assembly.

Fully referenced version, and London Rents Map text

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE