Recent Science Articles

Huppert’s right – MPs do need a crash course in science.

Is rookie Lib-Dem MP Julian Huppert right to suggest that MPs should be required to take a ‘crash course in basic scientific techniques‘?

Although some are clearly not enamoured of the idea, I think there’s ample evidence that Julian is on to something here, particularly in suggesting, by implication, that many MPs lack the skills and knowledge necessary to understand much of the information that’s presented to them on a regular basis.

Only the other day, Tory Health Minister Anne Milton provided a prime example of the merits of Huppert’s suggestion while making a concerted effort to reclaim the title ‘milk snatcher’ for a new generation of Tory ministers; continue reading… »

We’ve cloned food for centuries. Let’s have more of it

My nan was a dab hand at cloning.

No, I’m not bullshitting you. She may have died getting on for twenty years ago and I doubt very much that she ever saw the inside of a laboratory but nevertheless she had the art of cloning down to a tee. And its not my just nan.

There must easily be hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people living in Britain today who are equally well-versed in the art of cloning – they’re called gardeners.

Okay, so gardeners don’t actually call what they do cloning, the call it propagation.

continue reading… »

Ignoring science in government policy is bad for all of us

contribution by Prateek Buch

In October last year, Professor David Nutt was dismissed as the Chairman of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), following remarks he made in a lecture given in his capacity as an academic in the field of neuropsychopharmacology – substance abuse to you and I.

Dismissed is the operative word here – the Home Secretary, whom the ACMD advises regarding the classification of drugs, claimed at the time that in airing criticisms of Government policy in an academic lecture, Prof. Nutt was “stepping into the political field and campaigning against government decisions”.

“You can do one or the other. You can’t do both.”

Advising their government on matters of scientific fact, allowing the formulation of evidence-based policy, ought to be a most sought-after position amongst scientists. It is an honour accorded to those at the very zenith of their field of expertise.

Yet following a breakdown in the relationship between government and the research community the position of Government Advisor represents something of a poisoned chalice.

Many now see the way in which advisory committees are regarded as being symptomatic of the fractured relationship between government and science.

Principles

Professor Nutt’s dismissal brough fury at the ACMD – two members resigned immediately and several more followed – and Parliament’s Science and Technology Select Committee published a report asking the Government to issue a clear Statement of Principles as to how it would handle scientific advice in the future.

The Government did indeed draft such a statement, and yet Lord Drayson’s Principles fell some way short of what leading scientists, and indeed the Select Committee, had hoped for.

Of greatest concern to many was the inclusion in the draft Principles of statements such as this: “The Government and its scientific advisors should work together to reach a shared position, and neither should act to undermine mutual trust.”

This clause would appear to put consensus ahead of objectivity, not-rocking-the-boat ahead of holding policy-makers to account, cart ahead of horse.

Not to worry, we were told, as the Principles were just a draft, to be consulted upon. Indeed, Lord Drayson indicated in an interview with the journal Nature that some of the more controversial elements wouldn’t be in the much-anticipated final published Principles.

But the finalised principles retain much of what was objected to in the original draft – lines such as “Scientific advisers should recognise that science is only part of the evidence that Government must consider in developing policy” and “Government and its scientific advisers should not act to undermine mutual trust.”

The finalised Principles precipitated yet another high-profile resignation from the ACMD panel, and appear to entrench the view that this government has of scientific advice and its role in evidence-based policy making.

Implications

It’s not just the details in this story that make for disturbing reading – viz the ban on the currently-legal drug mephedrone, likely to be rushed out despite the lack of any concrete evidence as to its harm – it’s the implications for how all public policy will be made in the future that are more worrying.

In an age when scientific data underpins so much public policy – whether regarding genetically modified crops or strategies to combat climate change and everything in between – it is crucial that government receives the best advice on said data before committing the nation to a course of action.

If it continues to undermine scientists and treat their advice as subsidiary to political goals, who will have the confidence to stand up and be counted amongst those who advise the government on anything?

Decoding the Tory cancer policy

Healthcare provision NHS is, naturally enough, one of the more important battlegrounds on which the upcoming election is being fought – after the economy, of course.

Its area that has already thrown up its fair share of controversy, particular in regards to cancer services. Labour have been pilloried by the right-wing press over an unsubstantiated allegation that it specifically targeted some cancer sufferers with a leaflet attacking Tory plans to remove targets for providing access to cancer services, a media-generated furore that conveniently deflected attention away from a much more serious issue:

Only last week, the Tory’s putative Health Minister, Andrew Lansley, was torn off a strip by the Sir Andrew Dillon, the Chief Executive of the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for misleading patients over current policy on authorising new drug treatments for use by the NHS.

Unlike the cancer leaflets issue, this is no mere storm in a teacup but an issue that goes right to heart of the Tory’s manifesto plans and, in particular, to this statement from the Tory manifesto:

NHS patients rightly expect to be among the first in the world to access effective treatments, but under Labour they are among the last.

The key phrase here is ‘effective treatments’ – in fact it is precisely because the NHS (through NICE) is one of the few healthcare providers in the world that actually examines the evidence for the efficacy of new treatments, relative to existing treatments for the same condition/patient group, before approving them for use that we have to wait a little longer to access some new drugs than is typically the case in, for example, the United States.

Although the FDA does evaluate the effectiveness of new drugs, what it doesn’t do is assess their performance relative to the efficacy of existing treatments, an essential feature of the kind of cost-benefit analyses that form part of NICE’s evaluation protocols. That has a clear knock on effect on the work that NICE undertakes for the NHS. Because comparative studies aren’t required by the FDA in order to obtain a license in what is by far the largest and most important pharmaceuticals market in the world, the drug companies do not include their in the standard trial protocols. What NICE typically get to work with are hypothetical comparative models derived from combining trial data for the data for the new drug with data from separate trials of the current best available treatment. These models, which are initially provided by the drug manufacturers, are a constant source of dispute as, naturally enough, manufacturers are prone to cherry picking the data for their models to create the most favourable impression possible, all of which can easily lead to several weeks and even months of wrangling over the validity of these models, delaying the evaluation process as a whole.

This is the real choice that the two parties are offering cancer patients and it one that best illustrated with a case study of new drug, Dronedarone, which NICE is expected to approve for use by the NHS later this year.

Dronedarone, which is marketed under the brand name Multaq, is new drug treatment for atrial fibrillation, a common from of cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat), a condition for which there have been no significant advances in drug treatment for around 25 years.

Only 18 months ago, Dronedarone was being touted as the ‘next big thing’ for patients with atrial fibrillation and attracted glowing coverage in the Daily Telegraph, in a typically uncritical article which suggested that more than 300,000 patients in the UK could receive the drug, when it was licensed for use, and that it could prevent up to 10,000 stokes in that patient group every year.

In January this year, the drug hit the headlines again, on this occasion because an initial technical appraisal of the drug, which was licensed in the US in July 2008, recommended against approving it for use by the NHS. Inevitably, this was picked up by the media who ran the story in line with their usual narrative, under which NICE were accused of refusing the sanction of the use of the drug for bureaucratic reasons relating to its cost relative to existing treatments.

What’s much more interesting, and revealing, about these two stories, which were published only 16 month apart, it the very different estimate the later story gives for the number of patients who were thought likely to benefit from Dronedarone. From an initial 300,000+ cited in September 2008, this figure has now fallen to a mere 40,000, a drop of around 87%.

Clearly, something else was going on in the background – something that the Daily Express chose not to disclose to its readers.

What the Express didn’t mention

What has in fact happened was that, even before it was licensed, the trial results for Dronedarone had failed to live up to early expectations. In fact what the manufacturers own data showed was that, for the vast majority of patients with atrial fibrillation, Dronedarone was only half as effective as existing drug treatments for this condition, all of which are considerably cheaper because their patents expired several years ago, allowing them to be produced as generics.

As a result, although the drug was licensed by the FDA in July 2009 it was awarded only a restricted licence, one that limited it use to a specific subset of patients for the purpose of reducing the risk of heart-related hospitalisation where those patients also had one or more other significant cardiac risk factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure, a prior stroke or advanced age (i.e. over 70). This was, and still is, the only patient group for which there was clear evidence that the drug performs better than existing treatments.

Dronedarone is also required, in the US, to carry a ‘black label warning’ prohibiting its use with patients with two specific types of heart condition, both of which cause give rise to atrial fibrillation, after a trial that included patients with those conditions had to be stopped before it was completed because preliminary data showed that the drug doubled the mortality rate in those patients. That’s another minor detail that the Express chose not to mention.

This is precisely what NICE also found when it published its initial technical appraisal of Dronedarone in December 2009 and it explains why that appraisal came out against approving the drug for use in the NHS on the basis for which its initial application had been submitted. That is the other crucial omission from the Daily Express’s overheated article. Dronedarone was put forward for evaluation by NICE in November 2008, eight months before the drug was awarded it restricted license in the US and some four month before the FDA published its technical appraisal of the drug, in March 2009. Although the drug had been granted a limited license in the US in July 2009, a year after it was put forward for evaluation by the FDA, NICE were still in the position of having to evaluate Dronedarone as a potential treatment for patients that the FDA had already ruled out in the review, because that was what was on the application submitted by the drug’s manufacturer, Sanofi-Aventis.

After reviewing the technical appraisal and consulting with the manufacturer and range of other stakeholders (i.e. charities, patient support groups, etc.) NICE has now decided to recommend that Dronedarone should be approved for use by the NHS on broadly similar terms to that for which it is licensed in the US. This has been described by the Telegraph as a ‘U-turn’ – it isn’t. The post appraisal consultation that NICE undertook is a standard element in its review process and the higher cost of the drug, relative to existing drugs, was a fairly insignificant factor in the technical panels initial assessment – what actually matters was the fact that, for most patients, Dronedarone is less effective than existing treatments.

There is, however, one very important difference between NICE’s revised recommendation and the license terms set out by the FDA. Based on its evaluation of the research evidence NICE is proposing to approve the drug for use only as second-line treatment, i.e. one that will prescribed only to patients that meet the relevant criteria if existing treatment prove to ineffective or if the patient experiences any significant side-effect from those drugs.

(The FDA made no such recommendation)

This view is supported by a newly published review in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology which calls into question the value of the data quality and relevance to clinical practices from one of the key trials included in the evidence submitted to the FDA (and NICE) and cautions against the indiscriminate use of the drug in the face of efforts by its manufacturer to actively promote it for use ‘off-label’, i.e. outside the terms specified by the FDA license.

This is side to whole debate about patient access to new drugs that the public rarely sees, although if you are interested there’s a pretty good article here (may require registration) that does a fair job of explaining the controversy that this particular study has sparked off and the complexity of the issues it raises. Typically, disputes over the value of the evidence base for, and efficacy of, new drugs are played out well away from the public’s gaze on the pages of medical journals and other specialist publications. Only if something goes badly wrong, as happened with thalidomide, or if long-term follow-up studies emerge that raise significant questions about the effectiveness of particular drugs, as has happened relatively recently in the case of SSRI antidepressants (e.g. Prozac), does the public ever get wind of the kind of uncertainties and risks that remain in place, even after a new drug has been licensed for use.

For that reason, it’s actually very easy for the Tories to mislead the electorate by promising that cancer patients will receive faster access to ‘effective treatments’ even though what their policy actually amounts to is, for the most part, simply that of giving NHS doctors more scope to bypass the recommendations issued by NICE and prescribe new drugs off-label. That may give some cancer patients the drugs they want, but it in no sense offers them any guarantee that the treatment they get as a result will actually prove to be effective. Some may benefit, others may not – it’s even possible that some cancer patients may have their lives shortened or experience severe side-effects as a result of being prescribed new drugs either off off-label or under conditions in which their efficacy has not been adequately verified.

While the Tories may be able to promise faster access to new treatments, what they cannot legitimately promise is that those treatments will be effective, and that is the real debate that we should be having here, not to mention the challenge that Labour and other parties should be putting to them in response to this part of their manifesto.

Breaking: Simon Singh wins libel appeal

Fantastic news from the Royal Courts of Justice, this morning, where Simon Singh has won his appeal for the right to rely on the defence of “fair comment” in the libel action brought against him by the British Chiropractic Association.

According to one tweet, from Jack of Kent, the judgement cites both Orwell and Milton – If M’luds are breaking out Areopagitica as an authority in a case of this kind then this really is going to be the landmark decision that Singh’s supporters [including me!] have been hoping for.

What the Beeb didn’t say about breast cancer screening

This morning there are many women across Britain, not to mention a few charities, who will have woken up to what seems to be some very reassuring news:

Breast cancer screening does ‘more good than harm’

Breast cancer screening does more good than harm, with any over-treatment justified by the number of lives saved, say experts.

Mammograms can spot dangerous tumours, but might also detect lumps that are essentially harmless, exposing some women to undue anxiety and surgery.

But data suggests screening saves the lives of two women for every one who receives unnecessary treatment.

Even allowing for the generally abysmal state of science/medical journalism, as practised by mainstream news organisations, this is a story that I find particularly frustrating.

continue reading… »

Breaking – LHC working: No Black Hole

“ATLAS has seen collisions !” may not become as iconic a statement as ‘The Eagle has landed” but that tweet, sent by Prof. Brian Cox at 12:06 BST, marks the beginning of a new frontier in particle physics.

The Large Hadron Collider is working as expected and Switzerland is not – I repeat NOT – rapidly disappearing into an artificially generated black hole.

Gullible press taken in by CSI Woo York claim

In the last few days we’ve seen a couple of classic pieces of lousy and wholly uncritical technology churnalism in the media.

One, the spurious claim that ‘Facebook cause syphilis’ was quickly taken apart by Ben Goldacre despite the somewhat worrying refusal of NHS Tees to provide Ben with access to the data on which the ridiculous claim, which, rather alarmingly, was made by the trust’s Director of Public Health.

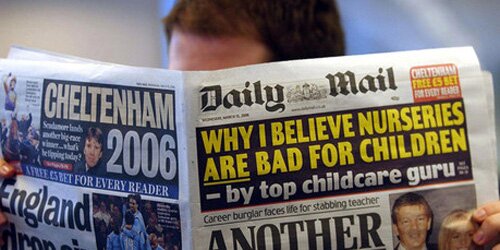

That leaves me to tackle this story, which emerged as wire copy from the Press Association and rapidly found its way into both the Daily Mail and The Sun before, worryingly, creeping into the industry press as well:

Typing technology ‘pervert trap’

Paedophiles using the internet to target youngsters could be tracked down – by the way they use a keyboard.

Researchers are investigating ways to use technology that can determine a typist’s age, sex and culture within 10 keystrokes by monitoring their speed and rhythm.

Former Northumbria Police detective chief inspector Phil Butler believes the technology could be useful in tracking down online fraudsters and paedophiles.

Professor Roy Maxion, associate professor at Newcastle University, has been carrying out the research in the US.

This is industrial-grade bullshit piece of advertorial from start to finish but, for reasons that will shortly become clear, still well worth picking to pieces.

Let’s start by telling you the truth about Dr Roy Maxion’s background and his actual research. continue reading… »

Dr Feelgood

Dear Readers,

I thought I had a terrible disease. I went to see 99 doctors, and they all told me roughly the same thing. That if I act fast and change my lifestyle in key ways I can avert the worst. But if I carry on as I am, I am going to get very, very sick. It’s not clear but I might even die. Or so they say.

Of course there are discrepancies between the exact diagnoses and projections each doctor gives me – but I guess that’s only to be expected, as medical science is a tricky thing.

Or is it? continue reading… »

What brain scans can’t teach us

Guest post by Tom Freeman

This month’s Prospect magazine has a section on neuroscience, and in particular its political implications.

One thing came up in their roundtable discussion that always gets my goat: the idea that neuroscience is going to be a good way of telling what effects on people different policies will have. Barbara Sahakian, a clinical neuropsychologist at Cambridge, says:

For years we changed our education system again and again, but these changes weren’t based on evidence about how we learned. Instead, wouldn’t it be useful if we thought about how the brain really works, and how children learn best, and in turn formulated educational policy based on that?

And the RSA’s Matthew Taylor adds, in a similar but more nakedly political vein:

I am confident that, as we find out more about our brains, it will strengthen the progressive case, in the sense that children learn best when they are actively involved, not being passive.

No, no, no.

Think about it: how could you use neuroscience to tell which teaching methods promote the best learning? continue reading… »

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE