Recent Libdems Articles

Two big reasons a Tory-Lib Dem coalition is unlikely after this election

Nick Clegg clearly wants another coalition with the Conservatives. And I’m fairly sure Cameron recognises the necessity of carrying on their tolerable relationship. And a lot of people in Westminster assume the two will be joined at the hip when negotiating post-election.

But I don’t think it will be that straightforward.

Firstly, it won’t be easy from the Conservative side. Theresa May and Boris Johnson want their shot at being leader of the party and neither have time to waste. Neither want to wait another five years either, when more of the recent crop of Tories will want their shot.

Tory leadership hopefuls could make the argument to colleagues that another coalition would undermine the Tory party and force them to break more promises. Besides, Cameron has shown himself incapable of winning elections outright, so why not get rid of him and get a proper leader who will win in 5 years time? – they will say.

Many Tories, who will not want the straightjacket of another coalition, will find that a seductive pitch and may reject another coalition.

Secondly, its not a done and dusted deal from the Lib Dem side either. For a start, Clegg has to get approval from his fellow MPs and party members, and that won’t be as straightforward this time.

There will be far more hostility from Lib Dems this time, for good reasons. These are some points made to me by Steffan John (@steffanjohn) over Twitter. I’m quoting him directly without embedding tweets to make it look cleaner:

1) Maths for majority isn’t there.

2) Even if a small majority was, no national interest in unstable government with 4yr leadership contest.

3) 2010 had financial crisis backdrop and 4) threat of swift re-election. Neither there this time, so less pressure on Lib Dems

5) 2010 had common ground on civil liberties, localisation, constitutional reform, environment, raising tax thresh. All gone.

6) Labour not hated as it was in 2010; Tories far more Right-wing now. LD won’t support again, esp. as Lab-LD-(SNP) is possible

Steffan John is a Lib Dem and makes some good points.

And here is Vince Cable’s former SpAd Giles Wilkes

So let the Tories, in minority, try to cut 12bn off welfare, 25bn off unprotected departments, w/o LibDems there to excuse it.

— Giles Wilkes (@Gilesyb) April 19, 2015

There is, I think, a real chance Lib Dems will reject a coalition with Cameron, especially if there are signs of hostility from Tory MPs (stirred up by May and Boris).

That clears the way for Miliband to be Prime Minister, with Lib Dems choosing to either work in a coalition or sit on the sidelines, while the Conservatives choose their next leader.

Five ways Ed Miliband and Labour can keep ex-Lib Dem voters in 2015

by Andy May

It was a strange feeling watching this week’s Labour conference. Once a political enemy, I could conceivably be voting for the party in 2015.

I joined the Liberal Democrats over a decade ago, and worked for two MPs. My parents are founder members of the SDP. I won’t go into my reasons for leaving – these are self-evident. Clegg is the best recruiting sergeant that disaffected centre-left voters Labour could ever want.

Instead let’s concentrate on five things Labour might do to convince the swathe of progressives who voted Lib Dem in 2010. These people hold the key to a Labour victory in 2015. Many of them, like me, are as yet undecided.

I have discounted the obvious… like not privatise the NHS or entrench inequality in education – plus there has been enough on energy already!

Here are five that specifically push Lib Dem buttons:

1. The Economy

Totemic policies such as the introduction of the minimum wage in the early Blair years have been eclipsed in the minds of voters by mismanagement and light touch regulation in the run up to the financial crash. Ed Balls made a shrewd move towards rehabilitation by announcing he would submit Labour’s spending plans to the Office for Budget Responsibility. But more reassurance will be needed. I want to see the positive role of the state championed without the irresponsible spending and incompetent implementation that came with the Blair era.

2. Environmental policy

Invest in renewables not fracking; tackle energy inefficiency in homes and vehicles; properly fund the Green Investment bank. Plenty more where that came from, but with the Lib Dems in government supporting a dash for gas and failing on initiatives such as the Green deal, Miliband has an opportunity to outflank my former party.

3. Democracy, lobbying and big money in politics.

Miliband is one of the most progressive leaders Labour has ever had on constitutional issues. He deserves more credit than he got for supporting Yes2AV, after fierce opposition from many in his party. He must support PR in the House of Lords, or local government along with party funding reform and lobbying transparency. This will only get noticed by 5-10% of the electorate, but many will be those all-important ex Lib Dem voters. To achieve this some in Labour will need to understand their party does not have a monopoly on progressive political thought.

4. Housing

Most of my twenty and thirty something friends cannot conceive of a time they could afford a deposit. 200,000 new homes a year by 2020 is welcome – the difficulty will be doing this in a sustainable manner that doesn’t wreck the same communities that would benefit from fresh housing stock. Frankly anything sounds good compared to the Governments half-baked Help to Buy scheme.

5. Civil Liberties

When Sadiq Khan claims Labour now the party of civil liberties all I can do is think back to 28 days detention, ID cards, illegal rendition… and laugh. I think it naïve to make such a claim although Sadiq’s personal record is commendable. Labour need to show they not succumb to scaremongering by the shadowy figures in the home office bureaucracy with clear human rights based framework to privacy and security, rejecting the authoritarian excesses of the last Labour government.

Here’s hoping Ed can do it if Clegg cannot. -his speech certainly warmed the cockles of my heart.

I and other social liberals and democrats would prefer not to be stuck in the political wilderness for the rest of our lives.

—

Andy May is a communications consultant, and formerly worked in as a constituency organiser for the Liberal Democrats.

Lessons for Labour from Eastleigh

My former boss Andrew Smith, MP for Oxford East, often spoke about the importance of good local campaigning. The aim of this, he argued, was to build strong relationships with the electorate, so that whatever was happening at Westminster or in the newspapers didn’t influence how people chose to vote. Rather than remote politicians having their views filtered through the media to the electorate, this is about local politicians and people working together, while the remote media chatter away in the background.

This isn’t a particularly new insight, but the value of this approach can be seen by the success of the Liberal Democrats in winning the by-election in Eastleigh. While the hundreds of volunteers, thousands of contacts and hundreds of thousands of leaflets over the past three weeks played their part; they actually won the election months ago, when they built their local organisation, made sure that people had a positive view of their local work, gathered the data and set up their delivery networks.

I think the key lessons for Labour from this by-election are not about whether “One Nation Labour” is reaching “southern voters”, or whether Labour needs to adopt policy x, y or z. Instead, the Eastleigh result poses two questions which Labour need to consider:

1. Why did Labour fail, in so many of the seats that we held between 1997 and 2010, to build the kind of local organisation which the Lib Dems have in Eastleigh?

2. How can Labour ensure by the time of the next election they have this level of local organisation in at least, say, 340 constituencies?

Over the past few years, as trust in politicians and politics has fallen, the added value of local campaigning and effective incumbency has risen. Parties which campaign all year round and mobilise volunteers well before an election beat those which wait until the last minute, whatever the national political context.

The value of ‘early intervention’, identifying and sorting out problems early and enabling people to develop their skills and talents, is just as evident in political campaigning as it is in public services. The Tories matched the Lib Dems leaflet for leaflet, door knock for door knock during the short campaign period. But six months, 1 year, 2 years ago, the Lib Dems were active and the other parties weren’t.

Arguably, Labour should have asked its volunteers not to head to Eastleigh, where the impact of their valiant efforts was always going to be minimal, but to Derbyshire, Staffordshire, Kent and other areas which have county council elections in a couple of months.

There’s a key challenge for local councillors here, as well. Voters in Eastleigh generally agreed that the local council was doing a good job, and that the credit for this should go to the Lib Dems. I wonder how many Labour-run authorities are places where people would spontaneously say that their council was doing a good job, let alone attribute this to the Labour Party? That should be a key goal for every Labour councillor.

Getting as many county councillors elected as possible in May is much more important for Labour than their share of the vote in Eastleigh, especially if those councillors are signed up and committed to talking to voters once they are elected, organising locally and building support well ahead of the next General Election. As Eastleigh shows, it is never too early to start getting ready for the next election.

Sex, lies and Liberal Democrats: What I knew about what happened

For 11 months from September 2006, I was the day-to-day organiser of the Lib Dem Campaign for Gender Balance, the party’s internal initiative to mentor, train and network female would-be candidates for Parliament.

Though managed by Jo Swinson MP, I was actually based in the party headquarters, my desk sandwiched between those of the Candidates and Campaigns teams, on the floor above the office of the then Chief Executive, Chris Rennard.

In my own life, these were important months. Galvanised into membership as a student by the heat of my opposition to the Iraq war and plans for 92-days detention, it was only when working right next to them that I saw how much else was missing that I also cared about- like class, redistribution and solidarity. Oh, and actually taking women’s under-representation seriously enough to do something about it that might work.

And it was also during this time that inappropriate sexual touching by Chris Rennard of Alison Smith was alleged to have taken place. I don’t now remember where I first heard about it, but I do remember the phone call when Jo told me she had spoken to Alison herself, and that the information had been passed to Paul Burstow, the Chief Whip. And I know that key members of staff at Lib Dem HQ were also aware of all this.

Naïve as it now sounds, I believed it was being dealt with, and that what I had to do was make sure Alison knew she would still get the campaign’s help if she chose to look for another seat. I left shortly afterwards, to become a law student and a Labour activist – things I now struggle to remember a life without.

Almost six years later, I was emailed by a researcher from Firecrest Films, who said she wanted to talk to me about “a possible short film looking at gender balance in political parties”. I could not have been more thrilled: the level of women’s representation in our Parliament is both embarrassing and damaging to sound policy, and cannot be fixed alone.

I wanted to talk about liberal ideology and its innate misunderstanding of positive discrimination, and the more prosaic issue of complacent local party officers who pay zero attention to the diversity of their membership until longlisting day. And yes- I wanted to talk about the questionable attitudes that some male politicians – in all parties- have towards young women.

But, of course, this wasn’t actually the purpose of the meeting at all. As I wittered on about shortlisting quotas and the great I Am Not a Token Woman scandal of ’01, it was impossible to miss the recurring theme of her questions. Those training events that in my view focused on the wrong aspects of what it takes to be a candidate- did, erm, did Chris Rennard usually come along? And did he stay over? Not even my hilarious Lembit Opik anecdote could throw her off.

So I adjusted my expectations, and told her what I knew. And having learned that, as far as we can tell, nothing was done about the allegations, I am wholly supportive of the Channel 4 investigation and the mounting pressure on the party leadership to explain who decided what.

What worries me now is that, as the coverage ramps up and up, and becomes increasingly politicised, we risk taking our eye off the wider issue of culture in all our political parties. Sexual harassment is hard to report anywhere- but it’s borderline impossible in a world where success means avoiding embarrassment at all costs, where new recruits can expect to be tested on their loyalty at least as much as their talent, and where employment rights don’t exist, because candidates are not employees.

There are answers to be developed here – from a cross-party protocol for handling allegations of candidate mistreatment, to opening up the remit of the existing Parliamentary regulators – but this won’t happen if scrutiny gives way to scandal. The commentators- from both politics and the media- must not look solely what was done, but about what will be done differently in future. And, in case any researchers want to hear my Lembit Opik story – I still think that short film on gender balance is a good idea.

How Labour will pressure Tories on the Mansion Tax

Last week Labour announced it would force a vote in the House of Commons on the Mansion Tax. This follows Ed Miliband’s speech on the issue.

Vince Cable has since told the Guardian that Lib Dem support would depend on how Labour phrased the motion.

I asked Ed Miliband’s office of their plans, and this is what I’ve been told.

We don’t know when the vote will take place yet. Labour are waiting for the government to grant an opposition day debate time, and will use that for a discussion of the Mansion Tax and a vote.

If the government don’t grant such a day before the Budget, I’m told Labour will try and force the issue anyway by putting forward an amendment to the finance bill (the upcoming Budget).

The Labour leadership are confident that the Mansion Tax will prove popular with voters and want to push it in Parliament any way they can.

What if they get the debate? I was told: “We want to show there is a majority in House of Commons on the Mansion Tax,” — which suggests that Labour will try hard to ensure they have Lib Dem backing on the motion.

Lib Dems are very lukewarm towards the 10p tax proposal; I’m told that will be left out of the motion, so Labour can reach a consensus with them on the Mansion Tax alone.

The motion won’t call for any binding action (they can’t) – which should make it easy for Lib Dems to support it.

A spokesperson from Ed Miliband’s office said that they hoped the vote would “put political pressure on the government” to seriously consider a Mansion Tax. That is as far as Labour can go for now, and if they get that I expect they’ll be happy with it.

It will be interesting to see if the Lib Dems will vote against their own proposal or side with Labour on it.

What voters really think of Labour

Lord Ashcroft has published some new polling research about public perceptions of the Labour Party. He argues that to win the next election, Ed Miliband needs to make clear to his supporters that there will be no return to the days of lavish spending, or fight an election knowing that most voters do not believe Labour have learned their lessons, and that many of his potential voters fear Labour would once again borrow and spend more than the country can afford.

I think the most interesting bit of the research, though, is about what people in focus groups say about recent political developments.

Firstly, a few focus group participants had registered Miliband’s conference speech. His being the son of immigrants was the fact that had made the most impact, and was not always regarded in an entirely positive light.

One ‘Labour considerer’ in Nuneaton noted, ‘He said recently he was over here because his parents were immigrants, and I wasn’t sure about that’, while another was reassured that ‘at least [his family] weren’t gypsies. Or one of those people who make bombs’.

In contrast, only a handful of participants had noted that Miliband had announced that Labour was a ‘One Nation’ party, and they had no idea what he meant by this, except that it might be about keeping the UK together rather than letting Scotland become independent.

Apart from Ed Miliband, the only other Labour politicians who were mentioned by more than one focus group member were Ed Balls (mixed views) and Andy Burnham (popular in the North West).

Best of all, though, was the response by someone in Thurrock who had switched to Labour since 2010, when asked to name some prominent Labour politicians:

“Michael Foot. No, I’m thinking of Heseltine. And there’s Galloway”.

Now that really is One Nation Labour – the party of Michael Heseltine and George Galloway.

Half Time Report: How are the Lib Dems doing?

Last week’s election results have generally been regarded as a disaster for the Liberal Democrats. A lost deposit in Corby, no victories in the Police Commissioner elections, no wonder Party President Tim Farron described it as a ‘painful day’.

Half way through the current Parliament, many are predicting that the Lib Dems will be wiped out at the next election.

However, I think that the election results were actually rather good for the Lib Dems, and show that their future may well be brighter than many expect.

The Police Commissioner elections could hardly have been more challenging for the Lib Dems. They were held on a single issue which the party has historically been tarred as ‘soft’ on, across large electoral areas which undermine their ability to deploy effective local campaigning.

And yet, in places like Kent in Tory Middle England and North Wales in Ye Labour Heartlands, ‘Independent’ Liberal Democrats were elected. In the Lib Dem heartlands of Devon and Cornwall, the Tory polled 55,257 to 23,948 for the Lib Dem candidate – but a further 34,780 voted for two ‘Independents’ – both of whom had been Lib Dem councillors.

Meanwhile, in Bristol, Labour activists claimed that ‘Bristol First’ candidate George Ferguson was a Liberal Democrat in disguise. Sure enough, Ferguson won easily in the traditional Liberal Democrat manner by ensuring that anti-Labour voters realised that it was a two horse race and persuading Tory and Lib Dem supporters to back him.

The Lib Dem coalition of support pre-2010 was made up of a small number of people who philosophically believed in economic and social liberalism, a larger number of people on the centre left, and a big group of people who didn’t like party politics and wanted to vote for someone independent minded who would [s]tell them what they wanted to hear[/s] be a local champion. Their challenge was always to ensure that their national policies didn’t get wide enough circulation to undermine their local campaigners (for example, people in the South West who want to leave the EU or tactical Tory voters who don’t believe in rehabilitating prisoners or an amnesty for migrant workers).

Over the past two years, Nick Clegg and his advisers have been determinedly trying to focus the Lib Dem vote down to those who would vote for a European style social and economic liberal party, a triumphant strategy which has been reflected in the opinion polls. As a result, in places without a Lib Dem MP, their share of the vote is likely to collapse at the next General Election. But under the First Past the Post voting system, the net impact of that will be a big heap of so what.

In places where they have an MP, however, then they can run as quasi independents. They can emphasise their independence from the government, point to good local works and remind people that the choice is between them and someone even less appealing. What the PCC elections show is that there are still a good number of people who will vote for the traditional Liberal Democrat two horse race anti-party politics offer, (albeit trading under a different brand name).

It probably won’t work everywhere where they currently hold seats. But if former Lib Dem party members can get elected to run the police in Kent and the council in Bristol, and if the Lib Dem leadership modifies even very slightly its political strategy of alienating all of their former supporters, then 2015 may bring another election with the Lib Dems holding the balance of power.

A sensible policy on drugs could be Nick Clegg’s legacy

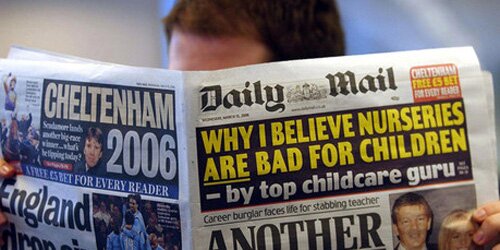

Whenever there’s a new, in-depth, excellently researched and extremely carefully worded report released which calls for a reform of our increasingly antiquated drug laws, it’s always worth going and seeing what the Daily Mail has written about it.

The UK Drug Policy Commission’s final report has then, as you might have expected, been giving the Mail treatment. Their article, which doesn’t feature on the voluminous front page of their website, does the classic trick of misrepresenting the report by picking on one comparison it uses.

Hence the Mail’s report claims the report says “smoking cannabis is just like eating junk food”, when it naturally says nothing of the sort. What it does say is (on page 108, PDF):

A small but significant segment of the population will use drugs. We do not believe that pursuing the goal of encouraging responsible behaviour means seeking to prevent all drug use in every circumstance. This is not to say that we consider drug use to be desirable. Just like with gambling or eating junk food, there are some moderately selfish or risky behaviours that free societies accept will occur and seek to limit to the least damaging manifestations, rather than to prevent entirely.

The Mail quotes the second half of the paragraph, but not the first part which makes clear why they’re making the comparison. Much of the rest of the Mail’s report is a fair summing up of the UKDPC’s conclusions, but it’s the headline and opening sentence that as always set the tone.

It’s a great shame, and shows exactly the hurdles that still need to be leapt through to get anything approaching sensible coverage of calls for drug law reform, especially as the report’s conclusions are thoroughly conservative and incremental rather than revolutionary.

It doesn’t advocate the decriminalisation of all drugs, let alone their legalisation; what it does suggest is that the possession of a small amount of a controlled drug could be made a civil rather than a criminal offence, leading to fines and referrals to drug awareness or treatment sessions rather than sanctions through the criminal courts.

Similarly, it suggests that either decriminalising or altering the sanctions for the growing of cannabis for personal use could strike a blow against the current situation where empty houses or warehouses are rented or broken into and used by criminal gangs to grow the high-strength strains of the drug that have caused such concern over recent years.

More optimistically, it calls for a cross-party political forum to be set up to examine where drug policy to go from here. Sadly, even if one were to be created, should it come up with the “wrong” conclusions and proposals then it’s highly unlikely it would get us any further.

With both the main parties clearly wedded to prohibition, regardless of how this report has apparently been welcomed even by the likes of Jack Straw, ideally there should be someone from the third party with a high profile who could make a break with the failed policies of the past by being clear about where we’ve been going wrong for so long.

Want a legacy that could eventually underline your role in the coalition, Nick?

Why ‘incumbency advantage’ may decide the next election

A lot has been written about how the constituency boundaries mean that Tories face a tough challenge to win the next election. For example, top pollster Peter Kellner argues, “For the Conservatives to win an overall majority, they need around a seven point lead in the popular vote.”

In contrast, the Mail on Sunday reports that Tory strategists ‘are confident that incumbency gives them an advantage’ as they plot how to win the next election.

Let’s have a look and find out who might be right.

The case that ‘incumbency advantage’ could make a large difference is that at the next election in a constituency which the Tories gained in 2010, the Tories will have benefited from having an MP building up their profile, recruiting volunteers, raising funds and campaigning for five years.

In addition, the Tories will have received over £150,000 per year in state funding for the MP’s salary, office costs, free postage of letters and a team of staff. Between 2010 and 2015, in the top fifty marginal constituencies which Labour is seeking to win from the Tories, the taxpayer will have provided in excess of £35 million to help the Tories defend their majorities. On top of this, these are all seats where Labour used to have an incumbency advantage (which will have helped them at the 2010 election), but where they are now forced to cope without these resources.

There are some numbers to test the ‘incumbency advantage’ hypothesis. Professor Philip Cowley reports that, ‘In 2010, Labour’s vote fell by an average of 7.4 percentage points in its seats that were not defended by the incumbent MP, more than two points higher than the equivalent statistic in seats where the incumbent stood again (–5.2).

The Conservative vote rose on average by 2.9 percentage points in Conservative held seats that were not being defended by an incumbent, but 4.1 points where the incumbent MP was still in place. And incumbent Conservative MPs who first won their seats in 2005 – and who thus had the opportunity to acquire a personal vote for the first time – saw their vote increase on average by 5.6 points.’

To estimate what effect this incumbency effect might have, let’s compare two scenarios. In one, we assume a close election, with some recovery for the government compared to the situation now, where Labour and the Tories each get 38% and the Lib Dems 15%. In the other scenario, we assume the same level of support nationally, but in addition apply a 2% swing to the incumbent in all seats where there is an MP restanding for the first time. This is a cautious estimate, when compared to the 5% swing to first time Tory incumbents which Joan Ryan found in her research on the 2010 election, but should give us an idea about whether this matters.

Using Electoral Calculus’ election predictor, the first scenario gives Labour 321 seats, 281 for the Tories and 23 for the Lib Dems.

But if we add in the effect of incumbency as above, then by my quick tally, we get 302 seats for the Tories, 298 for Labour and 25 for the Lib Dems. The whole of the supposed ‘bias’ in the electoral system towards Labour from the current boundaries disappears.

Let’s consider one further effect of incumbency. To get a majority, the Tories will be attempting to win seats from their coalition partners, the Lib Dems. Again, there is some evidence that Lib Dems benefit from having an incumbent MP. So let’s assume that the incumbency bonus above also applies to all Lib Dem MPs. Then we would end up with the following result:

Labour 298 Tory 294 Lib Dem 33

So, in summary:

Past evidence and local results since 2010 suggests that there is an ‘incumbency effect’, particularly for MPs elected for the first time in 2010.

The benefits of incumbency mean that it is harder for either Labour or the Tories to win an overall majority, as they have to battle against incumbent MPs who have large amounts of state funding to bolster their campaigns.

The Lib Dems are likely to do better than suggested by election predictors which don’t consider the benefits of incumbency.

Welfare reform shouldn’t just be about cuts

Labour’s spokesman on Work and Pensions, Liam Byrne, recently set out some of Labour’s ideas for welfare reform, and declared that if Labour was elected in 2015, there would have to be further cuts in the amount spent on welfare.

Now I’m all for saving money where it is being wasted. If more people were able to find jobs, then less money would need to be spent on support for unemployed people, because there would be fewer of them. If low paid workers got a pay rise, then the amount spent on tax credits would decrease. If we built half a million new council houses, then we wouldn’t need to give so much money to private landlords in the form of housing benefit. That’s even before we get into the corporate welfare dependency culture which guarantees hand outs for companies such as Atos and a4e for appallingly poor performance.

All of which goes to show that the key debate should not be ‘how much should we spend on welfare’, but ‘what should we spend it on’. I read an article in response to Byrne’s comments from Maeve McGoldrick of Community Links, which I thought got to the heart of this: continue reading… »

NEWS ARTICLES ARCHIVE